From Public Books:

LONDON. Michaelmas term nearly over. Implacable November weather predictably implacable. Forty-foot Megalosaurus presumably out there somewhere.

Readers may recognize a version here of the first lines of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. Dickens wrote Bleak House in 1852 and 1853, publishing it in 20 serial parts. As one did back in the day, he wrote Bleak House scratchily, noisily, using a goose quill pen, dipped at intervals into iron-gall ink, on cotton-rag paper. The material stuff that it took to write a novel such as Bleak House was very different from the stuff that writers use today.

Should you wish to read Dickens’s Bleak House manuscript (it’s close to illegible—I’ve tried), you can. You will find it safely on deposit at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, bequeathed to the museum by the wife of Dickens’s friend and biographer, John Forster. Most of Dickens’s manuscripts are safely housed in the Victoria and Albert. And as far as we know, the Bleak House manuscript is exactly where it belongs: snug in its archival box on a shelf, somewhere in or near the museum’s sprawling brick campus in South Kensington. Library staff diligently ensure that the air around that box remains at the right levels of humidity and temperature; that the room that houses the box remains secure; and that appropriate protocols govern how and where readers can have access to the work.

What’s business as usual at the Victoria and Albert Museum is far from the case fewer than four miles away, at the United Kingdom’s national public repository, the British Library. At the British Library, hopeful would-be readers of the library’s prodigious catalogue of unique, rare, and contemporary materials are out of luck.

On Halloween, 2023, the British Library suffered a massive cyberattack, which rendered its web presence nonexistent, its collections access disabled, and even its wifi fried. Moreover, the cyberattack also swept the personal data of the British Library’s humans—its users, but, far more extensively, its staff—into the hands of an outside party. During the final week of November, images of the stolen data were presented for auction on the dark web, for sale to whoever’s willing to pay 20 bitcoin, or about £600,000. By making the library’s digital infrastructure into a commodity (in an open, albeit dark, market), a “ransomware gang” calling itself Rhysida hopes to pressure the British Library to pay up first.

For good reason, this theft makes me wax existential: What did those cyberterrorists steal, when they stole the library’s entire digital footprint? What is a library, anyway?

. . . .

What could be more insistently analog than research on fragile pieces of paper, handwritten by authors in centuries long past?

I am writing this from desk 1086 in the British Library’s Manuscripts Room, on a Thursday in late November 2023. I arrived here this morning to continue work on a truly remarkable manuscript: Works and Days, the diary of the distinguished late-Victorian poet “Michael Field.” In this manuscript, you see, there’s an open secret: “Michael Field” is a pseudonym for two writers, both women, and also longtime lovers. My work is part of a larger effort to reframe what we think about Victorian life, writing, poetry, art, women, sexualities, and even dogs (for Michael Field were truly idiosyncratic), when we open the canon to such epistemological extravaganzas as those on display in this nearly 10,000-page double-diary.

Typically, this work is exhilarating to me; but today, it is uncanny, unsettling. I am the only reader present in what’s typically a bustling space. The library’s readings rooms are now zombies. As public service announcements have brightly reported, the rooms are still open for “personal study.” That said, visitors cannot request, retrieve, or use materials (for the most part), from the library’s vast collections.

Those collections are safe nearby. Yet as far as the digital world is concerned, they… do not exist.

What does exist is the stuff: the library’s collections themselves; the building and its desks, chairs, book cradles; even the odd cone-shaped paper cups at the public water fountains. Also here are the humans who conduct the operational tasks of this massive institution: the same humans whose personal data are splayed out on dark eBay for purchase, to be put to use in ways I shudder to imagine.

Not much circulation, retrieval, and return is happening at all; but still, the people who work at the library’s circulation desks, and on tasks involving the retrieval and return of books for readers, are here. They sit quietly. The security staff at the main entrance, and those at the doors of the various reading rooms, are here as well, and quiet as well. The locker room familiar to any regular library user is all but deserted, yellow and green metal doors ajar like so many flags on a windy day.

Here in the Manuscripts Room, the space itself looks the same, but it does not sound the same; depopulated, it is oddly quiet. Loudly quiet! This quiet is completely different from the constant rustle of ambient noise that counts as what we could call “library quiet.” Today, the distinctive energy of the Manuscripts Room is nowhere to be found: on a typical day, staff and readers alike are focused, on the clock, working swiftly and deeply, using fragile materials that are, by definition, unique and irreplaceable. This distinctive energy is the product of a thrilling alchemy of two forms of raw materials: readers, and the works in their hands.

Absent readers, absent works, the reading room is just a room. The ghosts of all the Christmases are stuck in storage.

. . . .

What could be more insistently analog than research on fragile pieces of paper, handwritten by authors in centuries long past?

I am writing this from desk 1086 in the British Library’s Manuscripts Room, on a Thursday in late November 2023. I arrived here this morning to continue work on a truly remarkable manuscript: Works and Days, the diary of the distinguished late-Victorian poet “Michael Field.” In this manuscript, you see, there’s an open secret: “Michael Field” is a pseudonym for two writers, both women, and also longtime lovers. My work is part of a larger effort to reframe what we think about Victorian life, writing, poetry, art, women, sexualities, and even dogs (for Michael Field were truly idiosyncratic), when we open the canon to such epistemological extravaganzas as those on display in this nearly 10,000-page double-diary.

Typically, this work is exhilarating to me; but today, it is uncanny, unsettling. I am the only reader present in what’s typically a bustling space. The library’s readings rooms are now zombies. As public service announcements have brightly reported, the rooms are still open for “personal study.” That said, visitors cannot request, retrieve, or use materials (for the most part), from the library’s vast collections.

Those collections are safe nearby. Yet as far as the digital world is concerned, they… do not exist.

What does exist is the stuff: the library’s collections themselves; the building and its desks, chairs, book cradles; even the odd cone-shaped paper cups at the public water fountains. Also here are the humans who conduct the operational tasks of this massive institution: the same humans whose personal data are splayed out on dark eBay for purchase, to be put to use in ways I shudder to imagine.

Not much circulation, retrieval, and return is happening at all; but still, the people who work at the library’s circulation desks, and on tasks involving the retrieval and return of books for readers, are here. They sit quietly. The security staff at the main entrance, and those at the doors of the various reading rooms, are here as well, and quiet as well. The locker room familiar to any regular library user is all but deserted, yellow and green metal doors ajar like so many flags on a windy day.

Here in the Manuscripts Room, the space itself looks the same, but it does not sound the same; depopulated, it is oddly quiet. Loudly quiet! This quiet is completely different from the constant rustle of ambient noise that counts as what we could call “library quiet.” Today, the distinctive energy of the Manuscripts Room is nowhere to be found: on a typical day, staff and readers alike are focused, on the clock, working swiftly and deeply, using fragile materials that are, by definition, unique and irreplaceable. This distinctive energy is the product of a thrilling alchemy of two forms of raw materials: readers, and the works in their hands.

Absent readers, absent works, the reading room is just a room. The ghosts of all the Christmases are stuck in storage.

Link to the rest at Public Books

Although PG hasn’t been in a physical library in several years, he shared the sadness of the author of the OP.

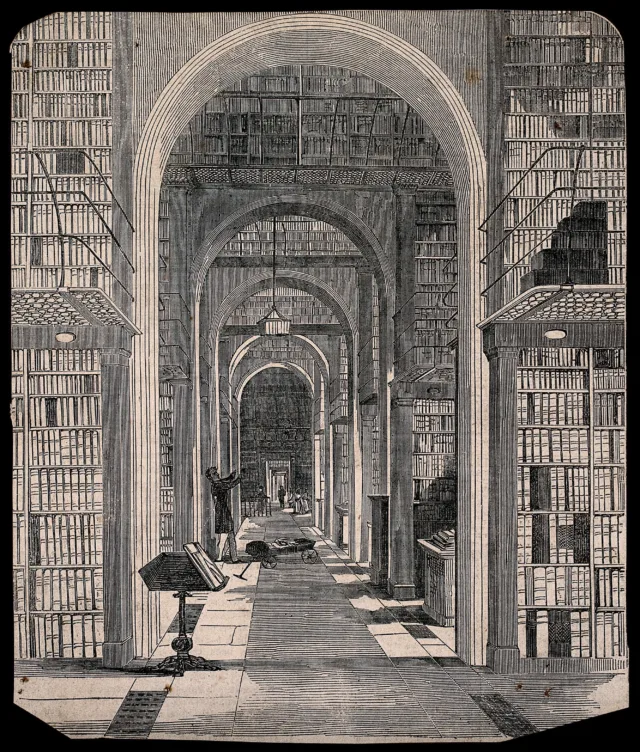

He can’t imagine how huge just the physical card catalog for the British Library must be.

He has a mental image of row upon row upon row of ancient and worn wooden cabinets, each with twenty rows of small card-sized drawers, each drawer with an ancient hand-written label like “dead – deaf” held in place by a tarnished medal frame with tiny ancient screws. The card cabinets stretch off into the distance with only a couple of patrons disturbing their their silent symmetry.