From Stratechery:

Yesterday the Supreme Court held a hearing in the case Apple Inc. v. Pepper. “Pepper” is Robert Pepper, an Apple customer who, along with three other plaintiffs, filed a class action lawsuit alleging that App Store customers have been overcharged for iOS apps, thanks to Apple’s 30% commission that Pepper alleges derives from Apple’s monopolistic control of the App Store.

There are three points to make about this case, and they are captured in the title:

- First, the specific antitrust doctrine at question

- Second, the question of whether the App Store is a monopoly

- Third, what the very existence of these questions say about Apple

In my estimation, these three points move from less certain to more certain, and from less important to more important. In other words, whatever the Supreme Court decides matters less than what the very existence of this case says about the state of Apple and its future.

Antitrust and Standing

The question before the Supreme Court is whether or not Pepper et al. have standing to sue Apple for antitrust violations at all; in other words, the case — which was launched in 2011 — hasn’t even started yet. The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 stated that “any person who shall be injured in his business or property by reasons of anything forbidden in the antitrust laws” can bring an antitrust action, but in the 1977 case Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, the Supreme Court held that only direct purchasers of illegally priced goods had standing to sue.

The specifics of the Illinois Brick case are helpful in parsing out what makes the Apple case complex; specifically, the Illinois Brick value chain was very straightforward: concrete block makers (including the eponymous Illinois Brick Company) were accused of colluding to fix prices for concrete blocks, which were bought by masonry contractors; masonry contractors in turn submitted bids to general contractors for construction projects, which were ultimately paid for by the State of Illinois. The State of Illinois sued for damages, alleging that the higher prices resulting from the price fixing had been passed through to the State of Illinois.

. . . .

In this value chain it is obvious who the direct purchasers were: masonry contractors; to the extent the State of Illinois suffered harm it was indirect pass-through harm. Thus, the Supreme Court ruled that the State of Illinois did not have standing; if every party in the value chain were to sue, the infringing party could be subject to duplicative recovery for damages (and parsing out the share of damages would be extremely difficult).

Apple vs Pepper

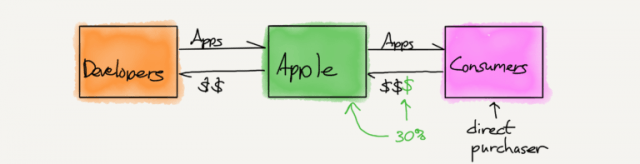

The question in Apple vs. Pepper, then, is who is directly harmed by Apple’s alleged monopolistic practices. According to the plaintiffs, the value chain looks the same as the concrete block manufacturers:

In this case Apple is in between developers and customers; the plaintiffs explain in their petition:

Apple charges apps purchasers a 30% commission on each app sale (unless it is a free app). The price paid by purchasers for an app is the amount set by the apps developer, plus Apple’s own supra-competitive 30% markup, both of which are paid directly to Apple, the alleged monopolist, every time an app is purchased. Apple keeps the entire supra-competitive portion of the purchase price for itself and remits the balance to the apps developers. The apps developers do not sell their apps to iPhone customers or collect any payment from iPhone customers, and iPhone customers are the only purchasers in the entire chain of distribution.

The plaintiffs argue that this makes consumers “direct purchasers”, giving them standing to sue:

Since Illinois Brick was decided 40 years ago, courts throughout the nation have had no trouble applying its “direct purchaser” standing requirement to various factual settings, including cases in which some form of payment is made to an alleged monopolist prior to the monopolist’s sale of a product.

Apple’s argument is that this misrepresents the transaction; the company wrote in its petition:

There is no basis for Respondents’ argument that pass-through damages claims are permitted whenever there is direct interaction between the plaintiff and alleged antitrust violator. This argument openly exalts form over substance by turning entirely on the formal identification of a “direct purchaser” and prohibiting any “further inquiry into the specifics of a case.”

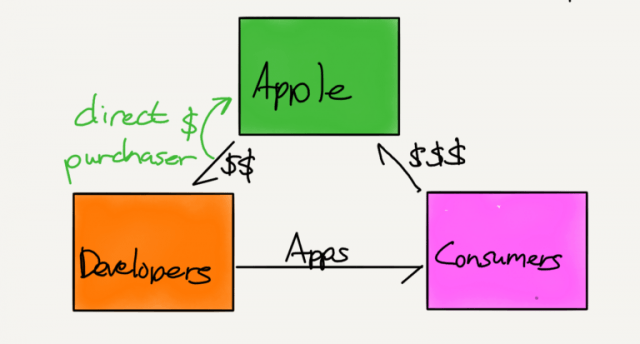

Rather, Apple argues that the value chain looks like this:

Specifically, the company argues that “Apple does not buy and resell apps”:

Respondents suggest for the first time that Apple “has adopted the role of a retailer functionally buying from developers as wholesalers and selling to iPhone owners as consumers.” But their complaint does not allege that. And Respondents have repeatedly acknowledged that only consumers buy apps; Apple does not. The Apple developer agreements cited by Respondents confirm this: developers “do[] not give Apple any ownership interest in [their] [a]pplications.” So Apple is fundamentally unlike a traditional retail store.

Rather, Apple acts as an “agent” for developers:

As Respondents note, [the Developer] Agreement confirms that “Apple acts as an agent for App Providers in providing the App Store and is not a party to the sales contract or user agreement between [the user] and the App Provider.” Thus, Respondents concede that the direct sale is actually between developers and consumers, facilitated by Apple as an agent and conduit.

Along those lines, Apple argues that developers set the price of their apps, which determines Apple’s 30% cut, and to the extent developers set prices higher to compensate for that cut they are passing on alleged harm to consumers — which means consumers don’t have standing to sue.

Link to the rest at Stratechery

PG says there’s nothing more bracing in the morning than a bracing dose of antitrust law. It tones up the mind and prepares it for broad gauge analytical work in any field.

That second diagram is not at all accurate. Unless you jailbreak your device (an action Apple claims violates your warranty on the device), you are not allowed to install an application package coming directly from a developer. Only applications coming from Apple will run on a stock Apple device. By design, Apple MUST act as an intermediary between developers and consumers in order for consumers to even install or activate apps on their devices.

Apple has little to worry about: the decision they’re appealing if from the nutty ninth. Rumor has it that they had 80% overturn rate as of 2010.

If the developer could get their app to the customer without going through apple – why would apple need to handle (take their cut of) the money?

“You smell that? You smell that?

That’s antitrust-law son, nothing else in the world smells like it. I love the smell of antitrust law in the morning.”

-PG with his morning coffee

Some say it smells like hydrogen sulfide but to me it smells like methyl mercaptan.

The smell of antitrust law is a combination of old motor oil and wet wool.

The smell of divorce law used to be cheap perfume. Now it’s cheap perfume or cheap after-shave.

Huh. I always thought that the smell of divorce law was dung . . . from all the crap the parties were flinging at each other.

LOL

/

pee-yew.