From The Millions:

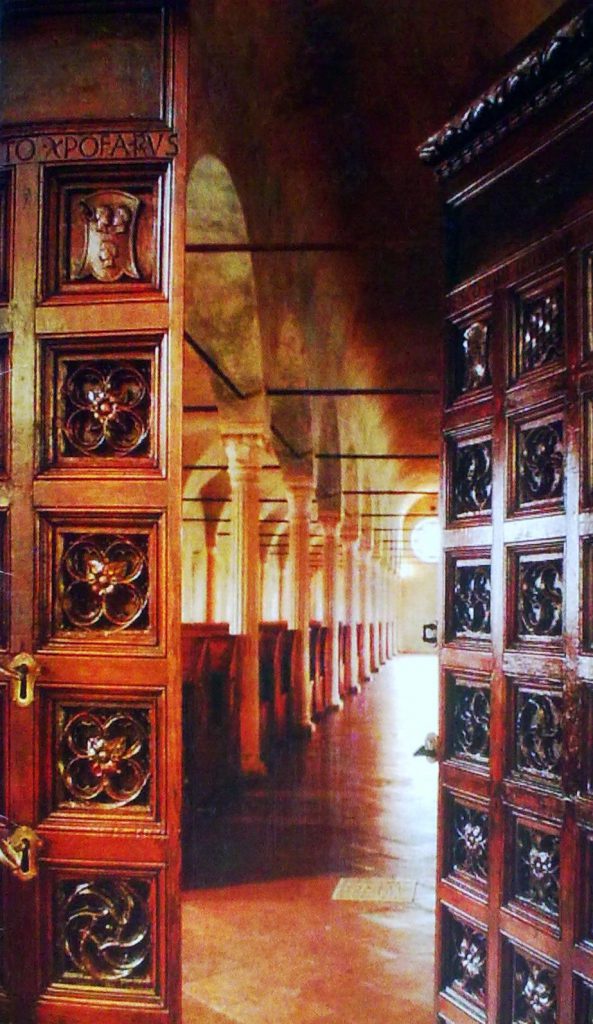

At Piazza Maunzio Bufalini 1 in Cesena, Italy, there is a stately sandstone building of buttressed reading rooms, Venetian windows, and extravagant masonry that holds slightly under a half-million volumes, including manuscripts, codices, incunabula, and print. Commissioned by Malatesta Novello in the 15th century, the Malatestiana Library opened its intricately carved walnut door to readers in 1454, at the height of the Italian Renaissance. The nobleman who funded the library had his architects borrow from ecclesiastical design: The columns of its rooms evoke temples, its seats the pews that would later line cathedrals, its high ceilings as if in monasteries.

Committed humanist that he was, Novello organized the volumes of his collection through an idiosyncratic system of classification that owed more to the occultism of Neo-Platonist philosophers like Marsilio Ficino, who wrote in nearby Florence, or Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who would be born shortly after its opening, than to the arid categorization of something like our contemporary Dewey Decimal System. For those aforementioned philosophers, microcosm and macrocosm were forever nestled into and reflecting one another across the long line of the great chain of being, and so Novello’s library was organized in a manner that evoked the connections of both the human mind in contemplation as well as the universe that was to be contemplated itself. Such is the sanctuary described by Matthew Battles in Library: An Unquiet History, where a reader can lift a book and test its heft, can appraise “the fall of letterforms on the title page, scrutinizing marks left by other readers … startled into a recognition of the world’s materiality by the sheer number of bound volumes; by the sound of pages turning, covers rubbing; by the rank smell of books gathered together in vast numbers.”

. . . .

There were libraries that celebrated curiosity before, like the one at Alexandria whose scholars demanded that the original of every book brought to port be deposited within while a reproduction would be returned to the owner. And there were collections that embodied cosmopolitanism, such as that in the Villa of Papyri, owned by Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, the uncle of Julius Caesar, which excavators discovered in the ash of Herculaneum, and that included sophisticated philosophical and poetic treatises by Epicurus and the Stoic Chrysopsis. But what made the Malatestiana so remarkable wasn’t its collections per se (though they are), but rather that it was built not for the singular benefit of the Malatesta family, nor for a religious community, and that unlike in monastic libraries, its books were not rendered into place by a heavy chain. The Bibliotheca Malatestiana would be the first of a type—a library for the public.

Link to the rest at The Millions

Here are a couple of photos of the Malatestiana Library:

.

.

Not fair. I never got to do research in any library that looked that lovely! 🙂