From Hacking Education:

This is the transcript of the talk I gave this afternoon at a CUNY event on “The Labor of Open”

. . . .

As I’ve thought about what I might say, I will admit, I had to do a lot of reflection about what my relationship is to “open.” Because it’s changed a lot in the last few years.

I don’t want to make this talk about me. That would be profoundly unhelpful and presumptuous. But I also don’t want to make that word “open” do work politically (or professionally) that it hasn’t done for me personally (politically and professionally). And while I understand that for many people “open” is a key piece of an imagined digital utopia, it hasn’t been always so sunny for me.

. . . .

At the beginning of the year, I made a bunch of changes to my websites – that is, my personal website and Hack Education, the publication I created almost a decade ago. I changed the logo. I updated my author photo. And I got rid of the Creative Commons licensing at the footer of each article.

My websites have always been CC-licensed – although admittedly, I’ve used different versions over the years, mostly going back and forth with whether or not I want that non-commercial feature. I guess, in some people’s eyes, that means my work was never really, truly “open.”

I thought a lot about this change, about ditching the CC licensing – this is my work, after all, and as such, it’s deeply intertwined with my identity. It’s also my experience – my lived experience – as a woman who writes online about technology.

Five years ago, I removed comments from my website. Lots of folks were not pleased. But dealing with comments was a kind of labor that I was no longer willing to do.

’d written a couple of articles that had ended up on the front page of Reddit and Hacker News – articles critical of Codecademy and Khan Academy, in particular – and my website was flooded with comments signed by Jack the Ripper and the like, chastising me, threatening me. “Just delete those comments,” some people told me. “Flag them as spam.” But see, that’s still work. Not very rewarding work. Emotionally exhausting work. Seeing an email appear in my inbox notifying me that I had a new comment on my site made me feel sick. So I removed comments altogether – that’s the beauty of running your own website. I felt then and I feel now that I have no obligation to host others’ ideas there, particularly when they’re hateful and violent, but even if they’re purportedly helpful – “there’s a comma splice in your last sentence.” Or “It’s a little off topic but anyone looking for a job should check out this website that is currently hiring people to work at home for $83 an hour.” You know. Helpful comments.

. . . .

But because I’ve removed the Creative Commons licensing, you now do have to do one thing before you take an essay of mine and post it elsewhere: you have to ask my permission.

As a woman who writes online about technology, I have grown far too tired of “permission-less-ness.” Because “open” doesn’t just mean using my work for free without asking. It actually often means demanding I do more work – justify my decisions, respond to accusations, and constantly rethink how and where I want to be and am able to be and work on the Internet.

So I’ve been thinking a lot, as I said, about “permissions” and “openness.” I have increasingly come to wonder if “permission-less-ness” as many in “open” movements have theorized this, is built on some unexamined exploitation and extraction of labor – on invisible work, on unvalued work. Whose digital utopia does “openness” represent?

. . . .

When we think about “open” and labor, who do we imagine doing the work? What is the work we imagine being done? Who pays? Who benefits? (And how?)

I talk a lot in my writing about “the history of the future” – that is, the ways in which we have, historically, imagined the future, the stories we have told about the future, and perhaps even the ways in which those narratives shape the direction the present and the future take.

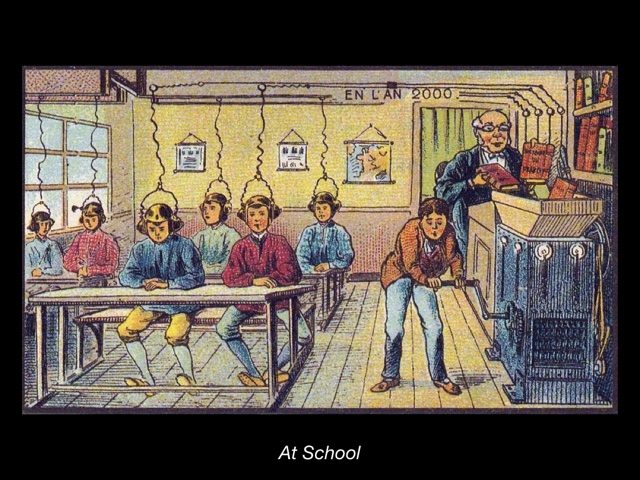

I’d like to turn to some of of these depictions of the future, a series of postcards that were created in 1899 in France to celebrate the turn of the century and to imagine what the world might be like in the year 2000.

Link to the rest at Hacking Education

Exactly. Information wants to be free makes a nice catchphrase, but where do the consumers of all this “free” information imagine it comes from? The people sharing their knowledge or creativity still need all the usual infrastructure of living, and that infrastructure must be paid for.

I realize I’ve sailed off on a tangent, but the remarks I quoted above (from Audrey Watters) struck a chord! 😉

J.M. Ney-Grimm, The Information wants to be free meme was a lie when Stewart Brand uttered it in 1984 (curious date, that), and it is still a lie today. IMO it will always be a lie.

To be fair to Mr Brand, he also said, “Information wants to be expensive,” and posited that there exists everlasting tension between these two poles.

Both statements are dead wrong.

Information is an inanimate construct. It wants nothing. It has no will whereby it could want.

There are those who want information to be free. They want to live off the labor of others. How very Venzuelan.

Richard Stallman distinguished between free — that is, without cost — and free to copy and distribute. If you think about this for more than two seconds you will see that this is no distinction at all. Once information becomes widely distributed and commonly available, the cost becomes zero.

From my years doing statistics, I can tell you that information is expensive. Back in the Neo-paleozoic epoch when I was in the bizz, the rule-of-thumb was that it cost $1 to get one question answered. That included the qualifying questions: “Excuse me, sir. Can you spare ten minutes to answer a short survey?” ($1) “Terrific. Are you older than eighteen and younger than thirty-four?” (+$1) “Thirty-five, you say? Thank you for your time, sir. Good day.” All these questions and responses were scripted, and, yeah, the scripts cost money.

A short, no-frills survey cost $75,000. Then. Anything worth doing went north of $100,000.

And these bozos want information to be free?

Any useful information is expensive. It was expensive to gather the data; the machinery and software to collate the data was expensive; and the machinery and software to analyze the data and put out meaningful information was expensive. Often, the data were too extensive to analyze on a PC or a workstation; you needed a mainframe. Expensive. When I was in the bizz, the only software that could handle the masses of data that we ran was SAS, and the subscription cost $8,000+ a month. And believe you me the education to know which analyses to apply was expensive and hard won.

Ask Coca-Cola the expense and lengths they go to in order to protect their formula. Ask a barbecue chef for the secret of his rub. Ask the US gov’t for the analyses of Russian sigint.

Then tell me information wants to be free.

on the other hand, look at the development of Linux.

It started by people donating their time to write code in exchange for the code that other people wrote.

or rather they gave other people the right to use their code only if the results of that use were available for them to use as well.

There are a lot of people who are interested in gathering information as a hobby, and the way they get satisfaction is sharing what they have gathered with others.

In this way, yes, Information is getting FAR cheaper than it ever was before, nearing free.

Think about road map information, 30 years ago, you would spend hundreds of dollars for a set of electronic maps to cover a relatively small area. “crowdsourcing”, or having many people working together (either explicitly via projects like open street map, or implicitly via apps like waze) has changed this so that information that used to be very expensive (or not available at all), is now free, and updated in near real time.

so saying that “useful information is expensive” if ignoring a lot of areas where useful information is so cheap as to effectively be free.

“Effectively free” isn’t free.

And neither are coop efforts; that is good old fashioned barter. People are still doing work in return for something they value. It isn’t raining down from the heavens like mana from a God.

Linux is a perfect example of how “free” isn’t free. Lots of companies detail salaried programmers to the various Linux (and other open source) projects in order to influence the development of the distros they monetize via support contracts, hardware sales, or access to the IP behind it.

Potluck software is no more free than a potluck dinner.

Just because you don’t see the costs doesn’t mean there aren’t any.

Thank you, Felix.