From Triple Canopy:

I have worked in Elmer Holmes Bobst Library and Study Center, New York University’s main research library, on Washington Square Park, for twenty-four years. I have always found the design of the building beautiful—more so than just about any other library building I have been in. Every day I walk through the revolving doors and gaze immediately upward toward the series of cascading bronze stairs, which ascend twelve stories. I stand in the ten-thousand-square-foot chasm, which is encircled with clinical precision by shimmering catwalks. The pattern of black, white, and gray marble on the ground floor resembles an Escher drawing viewed through the lens of the Italian Renaissance. The stark simplicity of the railings and the harsh, clean lines remind me of a Mondrian painting. My chest feels a little lighter and my head swims a bit, as when stepping into a cathedral and being drawn heavenward.

. . . .

Nearly every day, however, I hear someone complain that the atrium is a “waste of space.” This complaint goes back to 1965, when a group of head librarians from around the country were invited to review the architect Philip Johnson’s design. Among the librarians was Ralph Ellsworth, the director of libraries at the University of Colorado, who voiced his objections to Martin Beck, NYU’s director of planning. The enormous atrium meant that the floors would be U-shaped, which would minimize the amount of storage and inconvenience readers, he asserted. He called the design “a throwback to the 19th century conditions” and “a fantastic architectural anachronism,” comparable to Boeing putting “buggy whip holders on the front of a B-727.”

Ellsworth’s vitriolic letter set the tone, and librarians continue to vehemently denounce the building to this day. They allege that Johnson, like so many architects, failed to appreciate the purpose of the building or draw on the knowledge of librarians. They resent that the needs of researchers, and imperatives of storage and preservation, were deemed to be less important than the desire for grandeur and monumentality. And, unknowingly, they express an abiding tension between practical design and aesthetics, between librarians and architects, which has a curious history.

. . . .

In The Evolution of the American Academic Library Building (1997), Kaser argues that libraries should be designed to preserve materials, facilitate functionality, and attain beauty, but he admits that “very few have done all three.” As Kaser explains, there were no academic libraries in the United States until the mid-nineteenth century. Early American colleges tended to be small and religious, so at Yale and Brown, for example, the library shared space with the chapel. (Round libraries, such as the one designed by Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia in 1826, were also common.) In 1840, the University of South Carolina erected the first freestanding library, a classical edifice with four imposing columns at the facade. The next were built, in the Gothic style, by Harvard in 1841 and Yale in 1846. Harvard’s library was modeled after Kings College Chapel, built in Cambridge in 1446, and Yale’s on Trinity College, built in Dublin in 1732; both chapel-like structures exemplify the influence of ecclesiastical architecture on library design. While the earliest continental libraries were rectangular with perimeter shelving, the Classical and Gothic revival libraries in the United States featured an “alcoved hall with double-faced book presses extending inward between the windows in the two longer halls,” writes Kaser. Some libraries added clerestories with galleries that allowed for more shelving and also gave the impression of cathedrals.

. . . .

Librarians and architects were already at odds in the late nineteenth century, when librarianship and architectural practice were being professionalized. (The American Library Association was founded in 1876, the American Institute for Architects in 1856.) Many librarians felt that architects ignored their needs and created buildings that emphasized grandeur over functionality. William Frederick Poole, the librarian at the Chicago Historical Society and the founder of Poole’s Index to Periodical Literature, was one of the most outspoken opponents of such designs, which he saw as wasting space and pointlessly imitating churches. At a meeting of the ALA in 1881, Poole delivered a fiery speech against the “vacuity” of the new Peabody Institute Library in Baltimore. “The nave is empty and serves no purpose that contributes to the architectural effect,” he argued. “Is not this an expensive luxury?”1

Poole went on to propose that additional floors be created and that books no longer be relegated to the aisles, which would allow for the storage of 717,000 instead of 150,000 volumes. He suggested that books be classified according to “four grand divisions or departments of knowledge,” with each getting a separate floor and reading room, accessible by elevator. Then he returned to the long-standing relationship between libraries and religious edifices:

Why library architecture should have been yoked to ecclesiastical architecture, and the two have been made to walk down the ages pari passu, is not obvious, unless it be that librarians in the past needed this stimulus to their religious emotions. The present state of piety in the profession renders the union no longer necessary, and it is time that a bill was filed for divorce. The same secular common-sense and the same adaptation of means to ends, which have built the modern grain-elevator and reaper are needed for the reform of library construction.

Link to the rest at Triple Canopy

PG will not prognosticate on the future of the physical library, but personally finds it far more convenient to locate books online than in a physical edifice.

That said, PG things physical libraries should be grand and glorious.

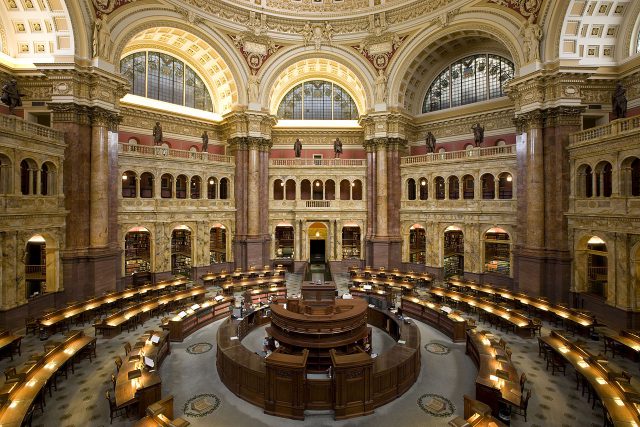

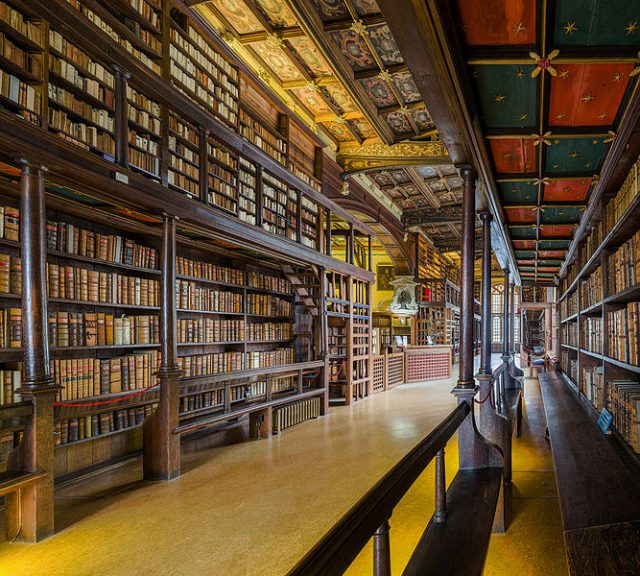

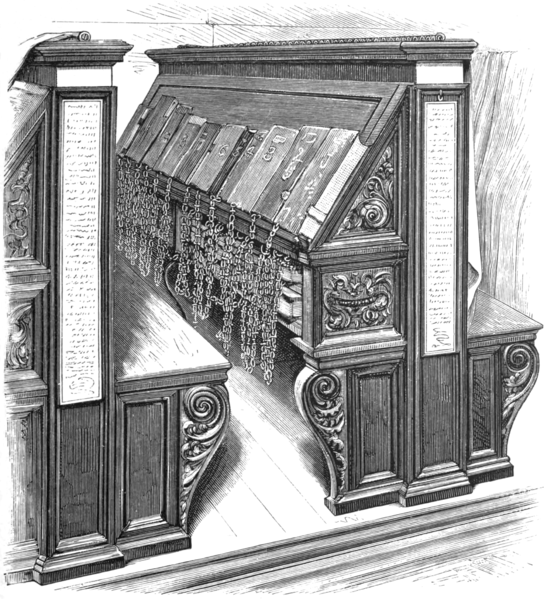

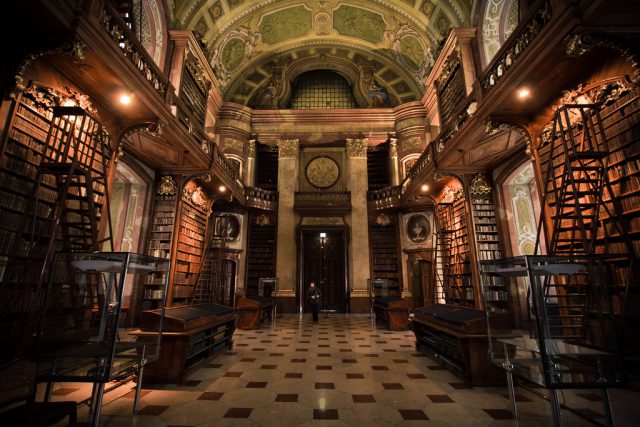

Here are a few he likes:

.

.

.

.

I adore all of those libraries, PG, practical or not!

But I admit the chains set me back a minute. My first thought was to wonder if they felt the need to chain the scholars down, rather than the books. 😉

Perhaps the readers felt so lightheaded after ingesting so much magnificence they grasped the chains in order to anchor themselves back in reality.

Seriously though I think the chains date back to a time when books were scarce and the thievery of them was a flourishing business.

I love that image!

But I think you’re right. Those books were probably worth several years wages – each!

“My chest feels a little lighter and my head swims a bit, as when stepping into a cathedral and being drawn heavenward.”

As it should. Even a small library can stir feelings of inspiration and wonder; a great library should, in its physical presence, echo the raising of consciousness and the growth of knowledge it contains.

If the ‘great’ library is so concerned with raising consciousness and inspiring wonder that it sacrifices 80 percent of its capacity to hold books (Peabody Institute: 150,000 instead of 717,000), just how great is it?

Like many a church, they can be grand or practical. 😉