From Kenilworth Books:

There is a great deal of social pressure in the book industry to be smiley and gushingly positive all the time – and we are, when it is appropriate. The many authors whose work we love, and the many small publishers in particular whose work adds so much to what we offer as an independent bookshop, we will support with all our strength. But every now and then someone has to find both the courage and the words to explain that something is not right (even if they are damned for it) and to try to make suggestions as to what needs to change.

. . . .

The British Book Industry has a monstrous fair-trade and exploitation issue skulking beneath the surface which is slowly suffocating everything – it needs to be dragged in to the light and be seen for what it is.

Discussion about having a fair-trading arrangement for the production and selling of books needs to be moved up a gear; we need a pricing agreement that is coupled with a covenant about the fair treatment of authors. I’ve spoken to authors and illustrators who have been told off and threatened by their publishers for commenting on, or even just for sharing our previous blogs – making all but the bravest less willing to add their experiences to the discussion, except privately. Oddly perhaps, I’ve had the same experience with publishers; half a dozen publishers, both large publishing houses and small independents have contacted me privately with words of encouragement, telling me that the pressure on them to release books to Amazon, WH Smith and the supermarkets at extremely high discounts is embarrassing, crippling to their profit margins and has been the catalyst that has changed the nature of their business and not, they feel, for the better.

. . . .

Our friends in indie bookshops across the country are heading to Parliament soon to meet and discuss the plans put forward by The Big Green Bookshop for an Alliance of Independent Bookshops. The initial proposal included a plan for indie bookshops also to secure higher discounts from publishers – enabling them to compete in a low-price war. It is important that all booksellers understand what happens when a book is discounted, and who it is who feels the burden of this discount culture the most.

. . . .

The moment I go to the publisher and request a higher discount, the royalty rates for the author start to creep lower. When the Net Book Agreement was removed we were in a pre-digital world, no one had anticipated the arrival of e-readers (even though the first model of the Kindle in 2007 sold out within just a few hours) or the growth of leviathan that is Amazon – and as a result no one expected that trade discounts, even when ‘liberated’ from the constraint of the Net Book Agreement, would go above 55%. But they rocketed to much higher, and in cases now some retailers are demanding more than 70% discount on books from the publisher – meaning that the royalties back to authors, which are tied closely in to the rate of discount, are also decreasing year on year.

. . . .

Many authors however are struggling; writers with thirty years’ experience and many dozens of important and successful books to their name, are living on their over-drafts, taking second jobs to make ends meet, surviving by their partner’s incomes, or realising that they can earn more money by not writing but by doing events based on previous books. I spoke to one prominent, award-winning writer who told me ‘I have produced more than 200 books in 30 languages; many of my titles have sold over 1 million copies, I have a stack of awards – and yet I have not yet earned out the £10,000 advance I was given to cover two years’ work, and struggle to make ends meet‘. I’ve met writers who, just to enable them to continue in their chosen profession, are borrowing money from relatives, who have moved abroad for a lower cost of living and many whose thoughts of giving up are so dominant that I think it is fair to say that there is a prowling mental health risk too.

. . . .

The royalty arrangements for authors are so complex that the vast majority of authors do not even claim to understand them. If you know an author well enough to ask, please get them to show you their royalty statement – what you’ll see is a standard 10% of the recommended retail price for a new hardback book but then a separate and much lower rate for ‘discounted sales’ and another lower rate for ‘online sales’ (Amazon). When you have a complex contract, a lot can be hidden, intentionally or otherwise. That 10% as a full price royalty is only for hardbacks. On paperbacks it is, as a standard, 7.5% – with variations. And royalties are different again when a book is prepared for export. Royalties can go up according to sales and over time – but only once an author has earned out the advance on a royalty (if there is an advance).

. . . .

On ‘Special Sales’ (of which more later) the terms are, as standard, 10% of publisher’s net receipts, but when that book is so heavily discounted, that equates to about 3% of rrp – so for a £1 book, and author gets between 2p and 3p. It is important too that we start to question the level of transparency when out-dated agreements underpin the entire industry.

. . . .

In economic terms the issue is not only one of fair apportionment but also of clarity of who takes the risk. I can already hear publishers and trade magazine writers shouting ‘The publisher! The publisher takes the risk’. Yes, certainly the publisher is taking much of the financial risk, and many of the smaller publishers are making very modest profits indeed as a result. However, they are not taking all the risk. By firing out huge numbers of books, placing marketing behind a few and leaving the others to sink or swim, the culture of large-scale publishing is pushing a huge part of the risk back on to the authors, whose remuneration is already low. On the face of it writers, as a producer of goods, have a low production cost – they work largely alone, at home, with minimal tools. And this is the way that the publishing industry generally views authors now – they are cheap producers. And if one gives up because they can’t make ends meet, there will always be another easily and cheaply obtained.

. . . .

The largest retailers seem to be in control of pricing and the perception of value, while the large publishers place themselves in importance far above the authors and illustrators on whose work they rely.

. . . .

Large retailers are demanding higher and higher discounts from the publishers and the publishers are protecting profits by using the antediluvian complexity of authors’ contracts and royalty arrangements as a cushion. Royalties are not protected in any way against either a publisher’s decision to discount, or a retailer’s demand for a discount. I hear from publishers that presence on Amazon is now prerequisite for sales success – a lack of presence there now seems to mean that other retailers won’t take it and reviewers won’t cover it; so publishers would say that they have little choice but to fall in with the demands made for 53-70% discounts. If the net revenue by the publisher then is only 30% of cover price, the author will get 30p of a £10 book, not the 60p they would have got had it been sold at a standard 40% trade discount.

. . . .

Many authors struggle to make any claim to their back catalogue of work, even when the publisher has no intention either of supporting the development of that author, or of ever re-publishing older books. Authors are having their perceived value, along with their incomes, reduced year on year. Few rights, dubious contracts, low income.

. . . .

In addition to this there are several murky areas of publishing about which we should all be concerned – ‘Special Sales’ is one that leaps to mind. This is when a publisher can sell on an author’s backlist (the author having little choice because of, again, contractual arrangements) to a company that will then produce the book to sell at very low price at discount stores, through catalogues or at book fairs. In this case, the author’s royalties are even lower: just 2-3%, while the publisher will take 60-70% of the profit with the books being printed at extremely low cost.

Link to the rest at Kenilworth Books

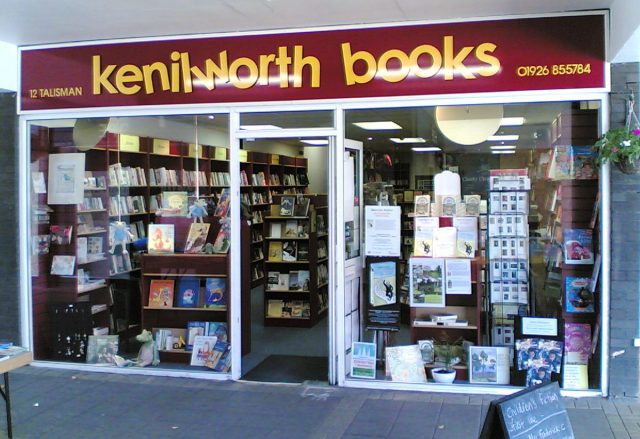

Kenilworth Books is a small bookshop located in Kenilworth, England. Kenilworth is located in Warwickshire, about 6 miles from Coventry in the West Midlands.

.

.

Neither the OP or the bookshop’s website identifies the author of this piece, but PG’s best guess is that the author is either an owner or manager of the bookshop.

In either case, PG found the OP to be quite insightful and well-written. Clearly, the author of the piece understands the book business very well and is familiar with the way authors are commonly treated by traditional publishers.

The gravamen of this article and the previous one PG posted from The Bookseller that appears immediately below is that publishers are killing their own industry by the way they treat authors and most booksellers.

A book industry comprised mainly of large publishers and Amazon is not a place in which publishers would find quiet lives.

On the one hand, Amazon pays indie authors much higher royalties than traditional publishers do. On the other hand, Amazon always wants to be the lowest-priced seller of goods, so the publishers’ margins will come under greatly-increased pressure.

If publishers’ short-sited pricing tactics squeeze physical bookstores out of the market, the publishers’ main advantage in the eyes of most traditionally-published authors – access to physical bookstores – will be gone. Barnes & Noble is teetering on the edge of collapse so, in the US, publishers won’t have any large customer who can purchase a wide range of physical books in large numbers other than Amazon.

PG suggests that, in early 2018, smart authors will keep as many options open as possible.

He further suggests that an author signing a traditional publishing contract:

- with non-compete and option clauses and

- royalty provisions structured to make it likely the author’s effective royalty rate will be well below the “standard” royalties that are always listed first in these contracts and

- that will last the rest of an author’s life and then some

- is the archetype of an author failing to keep her options open.

And, of course, traditional publishing contracts are always subject to assignment and sale, so the dedicated and experienced book people working for the publisher who romance the author into signing the publishing contract won’t last long if the publisher is acquired by a venture or distressed property financial type. If an author thinks present-day royalty statements are difficult to understand, wait until she sees the statements the new owners create.

> publishers are killing their own industry by the way they treat authors and most booksellers.

—

authors: why should they care? The slush pile is always full. Besides, most publishers would prefer to deal with agents anyway.

booksellers: There are still a few mighty chain stores, like dinosaurs not quite submerged in the tar pits, but the publishers’ important customers are the warehousers and distributors, higher up in the food chain from squicky bookstores, much less customers.

Sure, there are a few cases of author-publisher and publisher-bookstore sales, but those aren’t the rule. Normally the publishers operate at least one step removed from those who write their product and those who purchase it.

1. Amazon, through Prime, manages to deliver goods in two or so days. It has figured out how to warehouse, stock, and ship so efficiently that it makes money even on such fast delivery.

Bookstores and publishers could junk the returns policy (which is a killer for bookstores and wasteful for publishers) if publishers were able to ship to bookstores on a similar two-day schedule. Bookstores could reorder a particular title daily, if necessary, as they see how that title fares. The risk of having unsold copies on the shelves at the end of a book’s effective life would be close to zero.

2. That author of 200 books (romances, I suppose; no one writes so many histories or biographies) has seen several of them sell more than 1,000,000 copies yet still can’t cover a smallish advance. The royalties must be a few pennies per copy.

If an indie author sells 1,000,000 copies at the lowest efficient price at Amazon, $2.99, he makes about $2.05 per copy or $2,050,000 in all.

Last year, according to the Census Bureau, the average household income in the U.S. was $59,000. If an average working career is 40 years, that comes to $2,360,000. In other words, an indie author whose book sells 1,000,000 copies would earn 87% of what most households earn in a lifetime.

It’s a wonder to me how an author whose books have sold in the millions of copies hasn’t by now managed to purchase a few South Sea islands.

Amazon shipment is pretty quick, but that is only for existing merchandise. If they don’t have it sitting in their warehouse, it isn’t available. Amazon doesn’t produce the product, so their situation is significantly different from the publisher.

Publishers produce, stock, and ship. Amazon stocks and ships.

Publishers package and ship.

They don’t stock much these days of POD. 😀

And they don’t contribute anywhere near enough value to consider them a production player.

They’re middlemen. Like Agents. Like Ingram. Like Amazon.

They used to have almost-final say on what got to market but that power is gone.

Publishers produce the paper product that is sold to consumers. After production, they have something to package. That is their competitive advantage.

They are far more than middlemen like agents. Without them we would not have the widespread availability of books we enjoy today. That is far more than any agent does.

The people who finance, distribute and sell books are just as necessary to today’s book industry as any author. Like authors, they are necessary, but not sufficient.

And POD? That’s production.

Job printers produce the paper product that is sold to consumers. No major publishing house owns its own printing plant.

Exactly.

It’s just another deal.

Corporate publishing is all about deals and nothing but deals. That is not production.

Reminds me of, “If you’ve got a business – you didn’t build that.”

POD is packaging.

You’re falling into the cult of pulp trap.

Simple question: what is the product?

Is it the song or the movie or the disk it is packaged in?

Is it the corn or the can?

Is it the story or the file you downloaded?

Middlemen add value.

Good ones add a lot of value. Bad ones add negative value.

But adding value doesn’t make them producers.

When it comes to books the producer gets tbe copyright. Publishers don’t own the copyright, not even in Europe, where they are lobbying the Brusselcrats to declare publishing a creative act entitling them to ownership of a slice of copyright. In the US that isn’t even in the discussion and when Random House tried it in court tbe court made it clear it wasn’t going to fly so tbey ended up settling with ROSETTA.

https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/print/20021111/22822-rosetta-random-house-settle-e-book-lawsuit.html

If Random House were producers of the book they would have won at first motion instead of losing motions repeatedly. so they settled to avoid a full rout and Rosetta settled because throwing RH a few crumbs was cheaper than fighting to the end.

Dead tree pulp is just a delivery vehicle; packaging. Contracting with a printing plant to package a story is not production.

POD is packaging.

You’re falling into the cult of pulp trap.

No trap. POD can involve just the production of the books, or it can include production and packaging.

Simple question: what is the product?

The paper book with included content sold to retailers and subsequently consumers.

“It’s a wonder to me how an author whose books have sold in the millions of copies hasn’t by now managed to purchase a few South Sea islands.”

MC Hammer money management?

Expensive writing shacks all over?

Really high taxes?

(Astrid Lindgren, of Pippi Longstocking, was taxed 105% of income one year in 80’s SWEDEN.)

Real bad contract advice?

They only said the most recent one hasn’t earned out.

Maybe the other 199 sold better.

Making money is only half the story; keeping it is the other half.

Reminds me a little of some of Shatzkin’s posts. Intelligent but their insider viewpoint makes it almost impossible for them to understand and get it right. What the article is arguing for is basically government regulation of pricing, not at the upper level but the lower. Which will not in any event work for long, even if adopted.

The problem is publishers do not want to adapt to lower prices, instead dealing with the issue by making sure that the others in the process bear the cost, mainly the authors. The reason why the authors bear the cost is that the publishing contracts they sign are so bad that they mandate this. This is within the control of the publishers. Logically, the starting point of this article seems to be that the costs of discounting fall on the author, therefore we must limit discounting so the author to be treated fairly. Nowhere in the article is the responsibility for the authors bearing the brunt of the discounting placed squarely where it belongs, with the publishers. Therefore there is absolutely no consideration of the publishers (or even bookstores) bearing their share of the consequences of lower pricing. Of Publishers giving authors fairer contracts where the risk falls to the Publisher or at least shared.

The fact is that many publishers if not most are structured in a way that the new price levels will not support. They are bloated by the new standards and need to become leaner, more efficient operations. Out of all of the participants in the process, it is only the author who has little scope to become more efficient, though having said that many successful Indies have become much more prolific and are doing really well. Bookstores must also do their share. I think, for instance, that the costly and wasteful practice of “returns” is doomed and must be replaced by better inventory management. Amazon has shown what can be achieved in this regard,

Books are not special snowflakes. The Publishing Industry is not worthy of Government intervention to preserve its outdated business model and bloated structure. It is even less worthy because of the exploitative nature of this model. Whilst it is sad to see fewer bookstores, I’m sure some members of past generations mourned the fact that horses and buggies are no longer to be seen along our roads. Does anyone believe that legislative action banning motor vehicles would have saved those industries?

The article is an honest attempt by an insider to help authors and help bookstores, though sadly not to help the consumer. But it overlooks completely the elephant in the room.

Lost in all the discussions of forcing publishers to pay authors more is the legacy contracts. Those are signed, sealed, and archived. Terms fixed for life + 70.

Authors took their $10,000 advances and their $3000 advances or whatever and now they live with the deals they agreed to.

Authors (circa 2009) with older contracts traded half the ebook royalties for a couple points extra pbook royalty and thus helped make 25% of net the baseline for ebooks, ensuring ebooks give big publishers the boost in margins the OP now bemoans.

Too late they notice the beans weren’t magical.

Best they can do is negotiate new deals but until they stop signing the old deals in significant numbers they have no leverage. In the UK, at least, they sort-of recognize it and have been calling for government to step in and negotiate for them.

https://www.thebookseller.com/news/soa-seeks-new-law-protect-authors-323847

As somebody once said: “Now that’s a likely story!”

In the past, authors who wanted to publish had very little choice but to sign these disastrous contracts. Consumers were not the only ones to suffer. I feel very sorry for the authors who are stuck with these deals. The contracts were and are unconscionable.

I have little sympathy for authors who sign these contracts today. Yes, it seems most people don’t like change, but when there us a much better alternative available and it is refused? Perhaps it’s Stockholm Syndrome.

Government is not there to solve these problems and will not retrospectively abrogate these old contracts or alleviate their effects. There is no public interest case to do anything of the sort, nor do authors groups have the influence or money to lobby and procure such legislation. There is now a perfectly viable alternative which solves not only the authors remuneration problem but most of the other problems associated with the old oligopoly. For instance, I am often amused with the sometimes strident calls for publishers to embrace more diversity. It is too late. Publishers no longer control this. You want to publish, just upload to KDP. And, as an added advantage, the market will decide the degree of diversity that the public wants. The Gatekeepers are gone.

I wonder… Does this bookseller truly value authors the way he says he wants the BNPs to? Do you think he ever carries any indie author’s books in his store?

And all the hand wringing about publisher being pressured to discount their books? If I remember correctly, Amazon used to pay the publishers their wholesale prices regardless of what they sold the books for, but that made the publishers unhappy, too.

“And all the hand wringing about publisher being pressured to discount their books? If I remember correctly, Amazon used to pay the publishers their wholesale prices regardless of what they sold the books for, but that made the publishers unhappy, too.”

Yes, and when Amazon ‘lowered’ the discount on their pbooks they whined …

And I think this bookseller only values he himself being able to sell books, so the publishers selling books cheap to places like Sams/Cosco/Amazon means he isn’t making any money. The reason he whined abot publishers hurting writers is all those free-range ebooks – which also hurt his sales …

Hmm, looks like most B&M bookstores are doomed because the publishers won’t pay most writers enough to make it worth it to the writer to offer the publisher their story.

Online ‘bookstores’ can offer to sell a writer’s ebooks for a lot less and still pay the writer more per sale than the book publishers wish to – more bad news for B&M bookstore (and without have to drive somewhere where they might not even have the book you’re looking for.)

Hmm, looks like most B&M bookstores are doomed because the publishers won’t pay most writers enough to make it worth it to the writer to offer the publisher their story.

Do we have any indication publishers are having a hard time getting manuscripts to fill their schedule? They certainly face an unfavorable external environment, but it’s not because authors are holding back product.

Many authors have gone to eBooks and Amazon, and maybe publishers are only getting half the submissions they once did. If so, that half is a sufficiently high supply that competition among authors keeps the publishers well supplied with cheap manuscripts.

They keep throwing as much stuff at the wall as ever.

But the stuff doesn’t stick as well as it used to.

Isn’t the lower peak sales numbers for “bestsellers” evidence that the number of manuscripts remains sufficient to fill the slots but the appeal of the submissions isn’t as broad as it used to be?

After all, they keep blaming the books for the declines.

Isn’t the lower peak sales numbers for “bestsellers” evidence that the number of manuscripts remains sufficient to fill the slots but the appeal of the submissions isn’t as broad as it used to be?

That is one explanation, but we also might simply be seeing the effect of all the increasing supply of available books.

In the past, books passed out of retail circulation on a regular basis. Now, the book stays on the eRetailer shelf. Each new eBook is an incremental increase in the number of easily available books.

All the newly freed independent authors also make incremental additions each time they hit the Amazon KDP Upload button.

And then we have the backlist taking its place on the eRetailer shelves.

The available supply is no longer flushed out as it once was.

There hasn’t been a recent Harry Potter phenomenon, but I’m not sure that tells us much about the appeal of the available supply. The days of the blockbuster may be over.

And evidence that publishers have all the books they need for their schedule? All we have to do is look at how authors are low-balling their offers. These things have nothing to do with fair treatment of authors. It’s a game of market power, and competition among authors for publishers is so strong, authors’ offers sink.

Authors don’t make offers to publishers. Publishers make offers to a select few authors, take it or leave it. Those offers have been falling sharply because the publishers themselves no longer have the market power to ensure a large enough sale to justify the old contracts.

There are bids and offers. A buyer bids, and a seller offers.

If a seller doesn’t like a bid, he offers higher. If he likes the bid, he offers at the bid and makes a trade.

There are so many authors, they are competing with each other and offering books at lower and lower prices. If authors want to know why they get awful contracts, all they have to do is look at how many authors are trying to sell to the same bidder. The bidder just picks and chooses.

Amazon KDP is a great case study. Zillions of authors offer their books at prices lower that what had prevailed in the print world. Note all the articles we saw about the race to the bottom.

Then Amazon got in the game and created KU. Authors took advantage and offered even lower.

Walt Kelly put it well. “We have seen the enemy, and he is us.”

And the saddest thing of all is that so many excellent new writers (no matter how old they are) who produce high-quality books in any genre are simply unable to receive adequate compensation for their fine work even if they are lucky enough to be “discovered,” regardless of whether they go the traditional or indie route now.

Amazon’s KDP and KU graphically illustrate the concept of “a blessing and a curse.”

“Do we have any indication publishers are having a hard time getting manuscripts to fill their schedule?”

No, but we do have lots of indication that writers are skipping the publishers, which means not only do those publishers have no control over a growing percentage of the e/a/books out there for readers to find – but they aren’t getting a cut of the money those readers are paying (and the writers are making more on each sale than they would have with a publisher.)

As the publishers aren’t offering the readers e/a/books for the prices they want to pay, sales are down – and as there are easier ways of getting even the overpriced publishers’ books, bookstores are feeling it even more (we need only read the OP or watch B&N sink to see this.)

“Many authors have gone to eBooks and Amazon, and maybe publishers are only getting half the submissions they once did. If so, that half is a sufficiently high supply that competition among authors keeps the publishers well supplied with cheap manuscripts.”

Oh, so true! But they aren’t the only game in town any more, and they don’t seem to be getting the better manuscripts that they used to – and those they do get they still overprice the ebooks so even a ‘good’ ebook won’t sell.

They need to change how they treat writers or soon the only writer offerings they get will be from my dog …

They need to change how they treat writers or soon the only writer offerings they get will be from my dog

Like every other market, they will change when they have to. Bidders don’t high-ball when producers are low-balling.

In most of these articles, the fundamental supply problem and the resulting competition among authors is ignored. Authors will get what they want when there are fewer of them.

I think it may be that writers who are not as good (which may or may not improve) or not as confident in their own work if it is good (which has more potential to improve) are low-balling, but those who are both good and confident enough to know it seek other options if not offered a good deal by publishers up-front. And if it gets to the point where all the good authors are indie and all that publishers have to choose from are amateurs and wanna-bes, then it won’t matter how many of those they have; the reading public will still migrate toward the indie side because that’s where the books that are actually good will be. It’s not about supply of authors in general so much as supply of GOOD authors.

I think this is especially true when certain types of authors and certain types of books (wrong politics, “dead” genres/tropes, etc.) are getting rejected by publishers no matter how good the book actually is, in favor of books the big publishers think are “important”, the ones they want people to read but which may have only a small actual audience, no matter how boring or poorly-written those books may be.

Every first book is written by an amateur. Some are very good.

And most first books, nowadays, are not coming from traditional publishers at all.

Of course not. Most novels of any kind are not coming from publishers. With no barriers to entry, they flow to the Amazon KDP Button.

And many some of those amateur novels are very good.

Some are indeed good, and so are many.

“On the face of it writers, as a producer of goods, have a low production cost – they work largely alone, at home, with minimal tools.”

The highest cost for any business is its employees, more specifically compensating its employees for their TIME spent doing whatever they were hired to do, which is why when any business is in financial trouble the first thing they do is reduce their workforce somehow.

Good writers spend enormous amounts of TIME to create their works. They do not have a “low production cost” at all, but actually have a very high production cost that is all too often simply ignored by anyone who is not a writer, and all too often ignored or discounted by writers themselves. And, if indie, a writer’s TIME cost quickly rises when marketing and perhaps some distribution is also taken into account.

How much is a writer’s time worth? How much is YOUR time worth?

The highest cost for any business is its employees, more specifically compensating its employees for their TIME spent doing whatever they were hired to do, which is why when any business is in financial trouble the first thing they do is reduce their workforce somehow.

That is true of many businesses. But we can observe the author business doesn’t fit that model. Authors keep expending time year after year without making anything. This would normally be seen as “financial trouble.” But, authors keep on expending time.

This is why publishers give them awful contracts. They know the authors will keep on producing regardless of how much time is expended, and they know the authors will lower prices to the publisher by accepting the awful contracts. Authors are competing with each other.

In most other businesses, producers would stop delivering product, and go do something else. That reduces supply to the processors and pushes prices up.

The authors who keep on spending time without getting any return have a technical name in the business. They are called ‘hobbyists’. Most of the hobbyists have no discernable talent and can’t produce work of any commercial value: ask anyone who has ever read a publisher’s slush.

Good and skilful writers can find work elsewhere, and have been doing so now for many years.

How much does an author on KDP have to make before he leaves the ranks of the hobbyists?

I am hard pressed to understand why the difference between 60p and 30p (resulting from discounting or Amazon’s agreement) could ever be enough to sign one of PG’s contracts. I must be really stupid to be unable to see the attraction. Just sayin’.

Sorry, I misstated that. I meant one of the BPH contracts that PG refers to, not one for which he was in any way responsible. My apologies.

The OP tries to create a tight linkage between publisher discounting and the decline of royalties.

It could also use an editor for length.

Hence the call for “fair trade”.

As if making readers pay more would:

A- Change the predatory terms in the contracts already signed…

B- Convince publishers to do away with volume discounts…

C- Magically conjure up enough traffic to make up the unit sales lost to video, gaming, and indie publishers.

Fantasy Island?

Not even Mr Roark could conjure up any of those miracles, much less repeal price elasticity.

The system is broken.

It can’t be fixed.

It can only be replaced by a new system.

Those that get it are already acting on that reality.

The rest, pine for zero discount miracles.

‘I have produced more than 200 books in 30 languages; many of my titles have sold over 1 million copies, I have a stack of awards …

Well, that sounds impressive in and of itself. And like a great platform for going indie, if he/she is bored with the 10,000 pound advances. It’s not as if they’re vulnerable to the “tsunami of swill” slur, so why not?

With articles like this I feel like the mom in the “Joy Luck Club” who recognizes the importance of knowing your own worth. Why put up with crappy publishers who treat you like dirt? Kick them to the curb. You’re worth it!

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry after reading this. Talk about Titanic deck chairs and utter cluelessness… Methinks the author of the OP is living on Fantasy Island, but sans a happy ending.

None of the “steps” listed in the piece will have any effect whatsoever on the disruptions and changes underway in retailing, either in publishing or any other area.

These efforts are doomed.

Note that as a UK article, the term “fair trade” applied to books refers to price fixed books. Booksellers there still

pine for the Net Book Agreement declared illegal in 1990.

There are an awful lot of missing pieces in this story.

It is about the survival of bookstores, not authors. And many people don’t go to bookstores any more.

Bookstores are full of that marketing concept, inventory. Guesses about what will sell. A bookstore is required to look full – or people won’t even go in. Turnover has to be large to pay rent and salaries.

But the product is art, not a necessity like food. So, instead of people going in to buy predictable quantities of staples, and a few temptations every week, the category is optional.

They want publishing and bookselling to be rolled back in time (waves to the buggy-whip manufacturers) to where the options were 1) bookstores, and 2) libraries. Not going to happen.

In the current reality, it is almost impossible for bookstores to compete with online book purchasing. Amazon is trying – with an extremely limited model. The booksellers are almost completely out of that loop.

They also have to face (instead of suppressing and ignoring) the fact that their former model depended mostly on a limited set of white authors. With an occasional very lucky or very determined outsider.

I feel sorry for all those who refuse to see that things have already changed, and make themselves useful in the existing order, instead of the past, but legislation is, at the very best, a stopgap measure. A finger in the dike. It can’t turn back time.

Even I, a severely disabled person for almost three decades, have retrained myself – from scientist to novelist. Granted, I’m not going to make a living at it soon, if ever, but I didn’t have to – except that it’s what I taught my children: prepare to change, try to anticipate, and do it on your terms if possible.