From The Paris Review:

Our era is a digital one, to be sure, but libraries of physical books are still holding on defiantly, even triumphantly. According to the Library Map of the World, there are over two million public and school libraries on planet Earth. Of these, 103,325 are in the U.S. and 12,570 in my native Australia. Globally, the number of private libraries is much larger still—because who is to say that even a humble shelf of Penguin or Pocket paperbacks doesn’t qualify as a private library?

The census of American libraries spans a wonderful diversity of institutions, from modest municipal book rooms and mobile libraries to the grand collections of such hallowed places as the Morgan, the Folger, the Huntington, and the Smithsonian. Surveys of library users reveal a passionate attachment to these institutions, one that is voiced in very human terms. The word love is an emotion often expressed toward libraries, and not just on “Love Your Library Day.” Libraries are places in which people are born—as authors, readers, scholars, and activists. (Think Eudora Welty, Zadie Smith, John Updike, and Ian Rankin.)

Public libraries are of and for the people. Fundamentally democratic, they usually do not ask visitors to justify their presence or pay an entry fee. Fewer and fewer such nondiscriminatory and noncommercial spaces exist in our towns and cities today.

. . . .

There is a magic, too, of creation. How many great and minor works were inspired by and assembled inside library reading rooms and amongst the stacks?

Libraries have a strange potency that is hard to capture in the arid, bureaucratic calculus of inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Throughout much of the Western world, though, that calculus dictates how public funds are spent.

Fortunately some rules are made to be broken. In the U.S., Canada, and Australia (but less so in Britain) public libraries continue to be well resourced. We seem to have an innate sense of the value of libraries and the need to preserve them—notwithstanding the impossibility of counting all of their outputs.

Throughout history, the loss of libraries in war and conquest has been an appalling constant. In 2003, for example, priceless books and manuscripts were looted from Baghdad’s Archaeological Museum, National Archives, and National Library. Losses included six-thousand-year-old clay tablets, medieval chronicles, calligraphic manuals, and an irreplaceable collection of Korans. In an especially bitter twist, some of the lost books had survived an earlier onslaught, in which Mongol invaders threw plundered books into the Tigris to build a makeshift bridge of paper and parchment.

The destruction of books has always carried a peculiar power. There is no better way to extinguish a culture than to destroy its books. Even seemingly routine disposals—of old newspapers, magazines, journals, dust-jackets—can cause bitter angst and trigger a protective reflex.

Link to the rest at The Paris Review

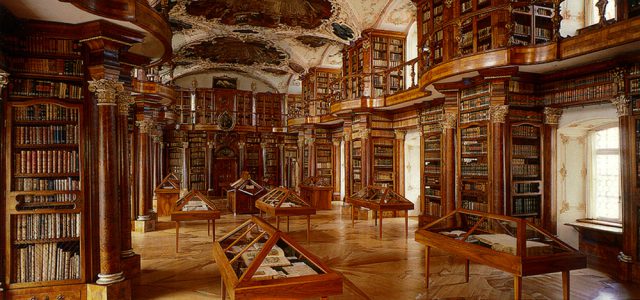

PG recently discovered (alas, online and not in person) The Abbey Library of St. Gaul. Here are a couple of photos (click on photo for a larger version):

.

Gorgeous is the right word. I want to visit!

Ooooh! Thanks, PG! These gorgeous photos made my day!