From The New Yorker:

In Lindsey Hilsum’s book “In Extremis: The Life and Death of the War Correspondent Marie Colvin,” there is a passage describing Colvin’s ordeal behind Chechen-rebel lines over Christmas of 1999. After coming under sustained Russian bombardment outside Grozny, the American-born reporter, then aged forty-four, was forced to trek out of the war zone over the snow-covered Caucasus mountain range to reach safety in neighboring Georgia. There were many bad moments, and, at one point, driven to exhaustion, Colvin considered lying down in the snow and sleeping. It was the opposite impulse of the one that drove her forward throughout her life. Colvin survived her Chechen experience and a dozen or more equally dangerous episodes during her twenty-five years as a war reporter, but, a month after her fifty-sixth birthday, in February, 2012, her luck ran out, in Syria. The Assad regime’s forces fired mortars into the house where she was staying, in the rebel-held quarter of Homs, and she was killed.

Colvin’s life has been memorably chronicled by Hilsum, a friend and colleague who lived and worked alongside Colvin in many of the same war zones, and whose home base was also London. (Full disclosure: I knew Colvin and am a friend of Hilsum’s.) At a time when the role of women is being reëxamined and has rightly galvanized public attention, Colvin’s tumultuous life has inspired a number of recent accounts, including the feature film “A Private War,” starring Rosamund Pike as Colvin. But it is Hilsum’s biography, written by a woman who both knew Colvin and had access to her unpublished reporting notes and private diaries—a trove of some three hundred notebooks—that seems to most closely capture her spirit.

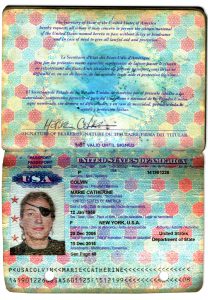

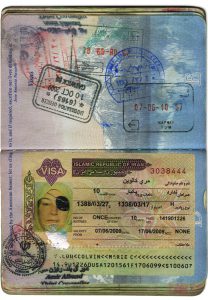

As told by Hilsum, Colvin’s life was an unreconciled whirl of firsthand war experiences—many of them extremely dangerous and highly traumatic—London parties, and ultimately unhappy love affairs, laced through with a penchant for vodka martinis and struggles with P.T.S.D. Colvin was a Yank from Oyster Bay, Long Island, and Yale-educated, and she wanted to follow in the footsteps of the trailblazing war correspondent Martha Gellhorn—her Bible was Gellhorn’s “The Face of War”—but she never wrote a book herself, and was little known to her countrymen, making her name, and the bulk of her career, instead, inside the pages of Rupert Murdoch’s Sunday Times, a British broadsheet with a tabloid soul. From 1986 onward, when the Sunday Timeshired Colvin, the editors appear to have happily taken advantage of her lifelong hunger for professional affirmation, a chronic willingness to throw herself into danger in order to get scoops, and her considerable personal charm, which, early on, earned her the trust of roguish political players like Yasir Arafat and Muammar Qaddafi.

Link to the rest at The New Yorker