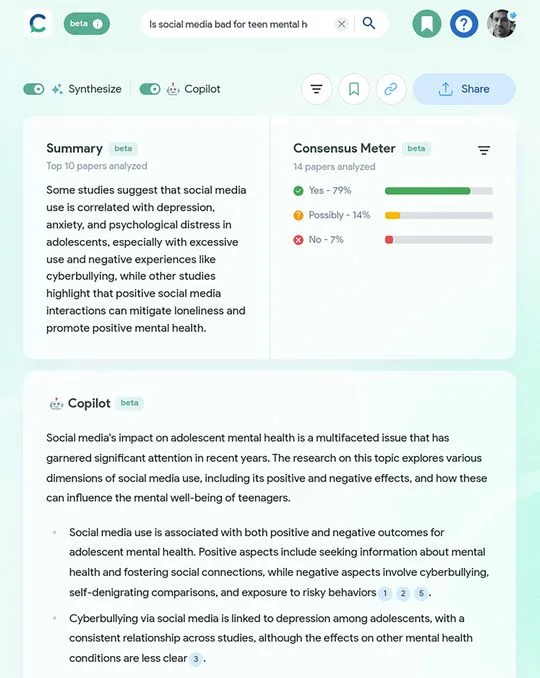

In his experiments with AI writing programs, PG has discovered a few strengths and weaknesses.

Following are the first few paragraphs of “The Sun Also Rises,” as originally written by Ernest Hemingway:

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton. There was a certain inner comfort in knowing he could knock down anybody who was snooty to him, although, being very shy and a thoroughly nice boy, he never fought except in the gym. He was Spider Kelly’s star pupil. Spider Kelly taught all his young gentlemen to box like featherweights, no matter whether they weighed one hundred and five or two hundred and five pounds. But it seemed to fit Cohn. He was really very fast. He was so good that Spider promptly overmatched him and got his nose permanently flattened. This increased Cohn’s distaste for boxing, but it gave him a certain satisfaction of some strange sort, and it certainly improved his nose. In his last year at Princeton he read too much and took to wearing spectacles. I never met any one of his class who remembered him. They did not even remember that he was middleweight boxing champion.

I mistrust all frank and simple people, especially when their stories hold together, and I always had a suspicion that perhaps Robert Cohn had never been middleweight boxing champion, and that perhaps a horse had stepped on his face, or that maybe his mother had been frightened or seen something, or that he had, maybe, bumped into something as a young child, but I finally had somebody verify the story from Spider Kelly. Spider Kelly not only remembered Cohn. He had often wondered what had become of him.

Robert Cohn was a member, through his father, of one of the richest Jewish families in New York, and through his mother of one of the oldest. At the military school where he prepped for Princeton, and played a very good end on the football team, no one had made him race-conscious. No one had ever made him feel he was a Jew, and hence any different from anybody else, until he went to Princeton. He was a nice boy, a friendly boy, and very shy, and it made him bitter. He took it out in boxing, and he came out of Princeton with painful self-consciousness and the flattened nose, and was married by the first girl who was nice to him. He was married five years, had three children, lost most of the fifty thousand dollars his father left him, the balance of the estate having gone to his mother, hardened into a rather unattractive mould under domestic unhappiness with a rich wife; and just when he had made up his mind to leave his wife she left him and went off with a miniature-painter. As he had been thinking for months about leaving his wife and had not done it because it would be too cruel to deprive her of himself, her departure was a very healthful shock.

The divorce was arranged and Robert Cohn went out to the Coast. In California he fell among literary people and, as he still had a little of the fifty thousand left, in a short time he was backing a review of the Arts. The review commenced publication in Carmel, California, and finished in Provincetown, Massachusetts. By that time Cohn, who had been regarded purely as an angel, and whose name had appeared on the editorial page merely as a member of the advisory board, had become the sole editor. It was his money and he discovered he liked the authority of editing. He was sorry when the magazine became too expensive and he had to give it up.

By that time, though, he had other things to worry about. He had been taken in hand by a lady who hoped to rise with the magazine. She was very forceful, and Cohn never had a chance of not being taken in hand. Also he was sure that he loved her. When this lady saw that the magazine was not going to rise, she became a little disgusted with Cohn and decided that she might as well get what there was to get while there was still something available, so she urged that they go to Europe, where Cohn could write. They came to Europe, where the lady had been educated, and stayed three years. During these three years, the first spent in travel, the last two in Paris, Robert Cohn had two friends, Braddocks and myself. Braddocks was his literary friend. I was his tennis friend.

The lady who had him, her name was Frances, found toward the end of the second year that her looks were going, and her attitude toward Robert changed from one of careless possession and exploitation to the absolute determination that he should marry her. During this time Robert’s mother had settled an allowance on him, about three hundred dollars a month. During two years and a half I do not believe that Robert Cohn looked at another woman. He was fairly happy, except that, like many people living in Europe, he would rather have been in America, and he had discovered writing. He wrote a novel, and it was not really such a bad novel as the critics later called it, although it was a very poor novel. He read many books, played bridge, played tennis, and boxed at a local gymnasium.

And here is what PG’s current most interesting writing AI, Perplexity, generated:

Certainly! Here is a creative rewriting of the first few paragraphs of “The Sun Also Rises” in the style of Ernest Hemingway:

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton. There was a certain inner comfort in knowing he could knock down anybody who was snooty to him, although, being very shy and a thoroughly nice boy, he never fought except in the gym.

He was Spider Kelly’s star pupil. Spider Kelly taught all his young gentlemen to box like featherweights, no matter whether they weighed one hundred and five or two hundred and five pounds. But it seemed to fit Cohn. He was really very fast. He was so good that Spider promptly overmatched him and got his nose permanently flattened. This increased Cohn’s distaste for boxing, but it gave him a certain satisfaction of some strange sort, and it certainly improved his nose.

In his last year at Princeton he read too much and took to wearing spectacles. I never met any one of his class who remembered him. They did not even remember that he was middleweight boxing champion.

I mistrust all frank and simple people, especially when their stories hold together, and I always had a suspicion that perhaps Robert Cohn had never been middleweight boxing champion, and that perhaps a horse had stepped on his face, or that maybe his mother had been frightened or seen something, or that he had, maybe, bumped into something as a young child, but I checked on all the stories I heard about Cohn, and found out that they were true. This passage maintains Hemingway’s characteristic terse prose, simple and direct language, and understated tone. It also reflects Hemingway’s focus on themes of masculinity and the effects of societal pressures on the individual.

Perplexity has a “Tell Me More” option at the end of its responses (at least in the paid version). PG hit the “Tell Me More” button and here’s what Perplexity provided:

Continuing in the style of Ernest Hemingway, the narrative would likely proceed with a focus on the disillusionment and existential themes that are prevalent in his works. Here’s an extension of the rewritten passage, maintaining the Hemingway style: After Princeton, Cohn was lost. Like many of us, the war had changed him. It wasn’t just the physical scars, those were easy to hide. It was something deeper, a sort of emptiness that came with seeing too much and understanding too little. He wandered through Europe, searching for something he couldn’t name. It was in Paris that he found Frances, and for a while, it seemed as though he might have found what he was looking for. But happiness, like a shadow, is elusive when chased.

Paris was a city that promised much but held back even more. It was filled with expatriates like us, all running from something, all trying to write the next great novel, paint the next masterpiece, or simply forget the past. The cafes of Montparnasse were our battlegrounds, where we fought against our own disillusionment with words and wit as our weapons.

Cohn wrote a novel during those years. It wasn’t particularly good, nor was it bad. It simply was. Like so much of life, it existed in that gray area between success and failure. Frances encouraged him, perhaps more out of a desire to secure her own future than any belief in his literary talents. But in the end, it didn’t matter. The book was published, and Cohn found himself a minor celebrity among the expatriate community.

Yet, fame, Cohn discovered, was as empty as everything else. He began to realize that the problem wasn’t with Paris, or his novel, or Frances. The problem was with him. He had been searching for meaning in a world that seemed determined to withhold it. And in that search, he had lost himself.

It was around this time that I met him. He was a man out of step with the world, clinging to the belief that somewhere, somehow, there was something real, something true. I couldn’t help but admire him for that, even as I pitied him. For in the end, we were all lost, all searching, all hoping for the sun to rise on a new day that would bring with it some semblance of meaning. This continuation captures the essence of Hemingway’s themes: the search for meaning in a post-war world, the disillusionment with the “Lost Generation,” and the personal struggles of his characters as they navigate their lives. Hemingway’s writing often explored the complexities of human emotions and relationships against the backdrop of a world that seemed indifferent to individual suffering, and this narrative aims to reflect those elements.

End of Perplexity Rewrite

PG says Papa doesn’t have anything to worry about.

Postscript:

During his web-wandering in connection with this post, PG discovered something else of interest:

The Unpublished Opening of The Sun Also Rises

by Ernest Hemingway

Also includes:

Letter to Ernest Hemingway on The Sun Also Rises

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

This was published in a now-defunct periodical titled Antæus No. 33, Spring 1979, edited by Daniel Halpern. You can read this Unpublished Opening/Fitzgerald Critique article Here.

If you don’t have a copy, you can read The Sun Also Rises, with the opening Hemingway used after seeing Fitzgerald’s letter Here.