From The Los Angeles Review of Books:

After the publication of Whiskey Tales in 1925, things were looking up for Jean Ray. This debut collection earned him recognition from, among others, Maurice Renard, who called Ray “the Belgian Poe.” Sadly, Ray’s bright literary future darkened all too soon: on March 8, 1926, he was arrested and incarcerated. Contrary to the legend, which Ray himself helped perpetuate, he was charged not with smuggling alcohol but “misappropriation of funds” concerning his literary journal. His publisher promptly cut Les Contes du whisky from its catalog and canceled two subsequent collections. Ray, aged 38, found himself in a cell in Ghent’s De Nieuwe Wandeling prison, where he would spend three years.

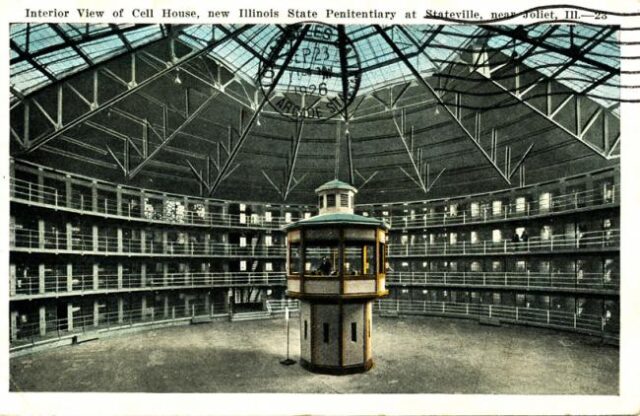

De Nieuwe Wandeling (“The New Promenade”), which first housed inmates in 1862, was inspired by the 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s design for the most efficient institutional building. A rotunda with an observation post at its center, Bentham christened his ingeniously baleful brainchild “the panopticon” (from the Greek word for “all seeing”). The devilishly clever detail is that the central observation post is installed with blinds, preventing the prisoners in the surrounding cells from knowing when (or if) they are being observed. As Bentham puts it in Panopticon, or the Inspection-House (1791), inmates constantly face “the apparent omnipresence of the inspector […] combined with the extreme facility of his real presence.”

Bentham’s italicized phrases help bring into focus the eerie atmosphere of the tales in Ray’s second collection, Cruise of Shadows: Haunted Stories of Land and Sea (1931) — all written during his incarceration. In almost every story, a narrator finds himself confronted by an “apparent omnipresence” of malevolent intent — sometimes from physical objects themselves — only to discover a real (if inscrutable) “presence” that means him no good. It is as though Ray channeled into his fiction the isolation, gloom, and, most of all, the unobservable presence of watchful eyes he endured within the quaintly named “New Promenade” panopticon. Imprisonment even marked Ray’s language: as translator Scott Nicolay points out, the three most frequently used words in the book are tumulte, clameur, and gifle — the last rendered as “smack” or “slap,” the sound of a bare foot hitting the cold stone floor of a cell. In the opening story, “The Horrifying Presence,” the unfortunate gold prospector, distinguished (to borrow Nabokov’s phrase) by being “ideally bald,” thus describes first hearing the “presence” outside his hut: “Footsteps on the ground outside, quite clear, like sharp little smacks [gifles].” He calls the invisible stalking entity simply “the thing.” Here, the bald prospector is — like many of Ray’s characters — telling others about his fearful encounter with the Unknown [l’Inconnu].

The Unknown, however, pervades Ray’s work not only because it is (or can be) terrifying, but also because it acts as shorthand for the way the stories repeatedly stage his characters’ groping for the words needed to capture what cannot be firmly grasped: the mystery shaping what is said. In “Dürer, the Idiot,” the narrator, another unfortunate soul who has had to confront the incomprehensible, reflects: “Our intellect demands a prelude for every event. It has a horror of the instantaneous and expends three quarters of its power in an effort to anticipate. It wants to come at all things by a gentle slope.”

This kind of ruminative aside, in the face of that which does not abide rumination, is typical of Ray’s style. During their walk along “a narrow street of the old town, a street of dark gables,” the narrator sees his companion, Dürer, suddenly make “the most peculiar gesture, as if he meant to grab my arm,” and then dash through the open door of a “little pink and green house” — never to be heard from again. This little house magnetizes the narrator, causing him to dream strange dreams. Toward the end of the story, when he watches a door open on its own inside the selfsame house, his intellect is floundering: “I turned my eyes once more to that straw of common sense adrift upon the lonely ocean of my terror.” This response is understandable, given that even the furniture prompted him earlier to say: “I stared with suspicion at lifeless objects like armoires and chairs[.] […] Has it ever struck you, the hostile attitude of some piece of furniture, familiar and inert among the others?”

Link to the rest at The Los Angeles Review of Books

Following are a couple of examples of panopticon prisons.