Note from PG – Following are brief excerpts and a few images from a much longer online exhibition from the Yale University Library. As usual, you’ll find a link to the exhibition at the end.

PG notes that, in his opinion, the Yale exhibition is better organized and constructed than most online art/design exhibition he has seen elsewhere and is definitely worth a visit if you have any interest in Ms. Wharton or the interior and exterior architecture in which she lived and where she set many of her books.

From at Yale University Library Online Exhibitions:

One century ago, Edith Wharton (1862–1937) published The Age of Innocence, a novel that has become one of her most beloved works. Less known is her first full-length publication, an 1897 interior design treatise titled The Decoration of Houses. Wharton’s keen interest in architecture and the design of interiors and gardens remained with her throughout her career. While she published novels, stories, poems, and nonfiction, she directed the design of her homes, from her country estate The Mount in Lenox, Massachusetts, to her New York City residence on Park Avenue.

. . . .

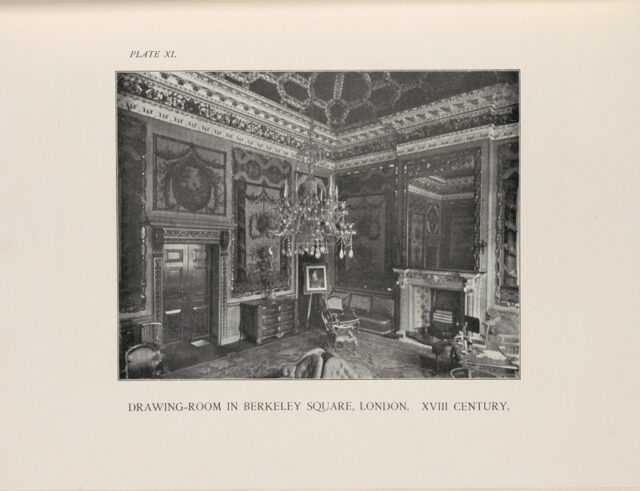

This exhibit focuses on Wharton’s treatment of the drawing room, known to her as a female space during a period of limiting gendered customs. In the world she describes in much of her writing, the drawing room was a specific sort of sitting room to which women would traditionally “withdraw” following dinner. The drawing room was also a space in which women could spend their days and receive guests. As such, drawing rooms provide a particularly rich context for understanding Wharton’s elite New York City society at the turn of the twentieth century and the role of women within it.

. . . .

Though written in 1920, The Age of Innocence is set in the elite New York City society of the 1870s—the world in which Wharton grew up. The novel unfolds from the point of view of Newland Archer, who is engaged to May Welland but in love with Ellen Olenska, who has escaped an unhappy marriage to a Polish count and returns to the New York City community of her youth. In her autobiography, A Backward Glance (1934), Wharton describes the writing of The Age of Innocence in the context of the extreme sense of loss she felt following World War I and the 1916 death of her dear friend and fellow writer Henry James. “Meanwhile I found a momentary escape,” she writes, “in going back to my childhood memories of a long-vanished America.”

Wharton recalls showing a passage of the manuscript to a trusted friend, Walter Berry, who responded that he enjoyed the manuscript, but that he and Wharton were “the last people left who can remember New York and Newport as they were then, and nobody else will be interested.” As proven by the novel’s great success, Berry’s prediction did not come true.

Wharton is best known as a writer of fiction. But her entrance into the world of writing occurred with the publication of The Decoration of Houses in 1897. Together with Ogden Codman, Jr., Wharton composed this treatise on interior design—her first full-length book.

Wharton and Codman had become friends when she asked him to help her decorate and make alterations to the house that she and her husband had recently purchased. In her autobiography, Wharton notes the unconventionality of such a choice. She writes that “the architects of that day looked down on house-decoration as a branch of dress-making, and left the field to the upholsterers, who crammed every room with curtains, lambrequins, jardinières of artificial plants, wobbly velvet-covered tables littered with silver gew-gaws, and festoons of lace on mantelpieces and dressing-tables.”

Wharton and Codman sought a more straightforward aesthetic for their interiors. They believed that “interior decoration should be simple and architectural.” Simplicity was crucial, in response to rooms cluttered with objects like those they describe in the colorful list quoted above. Wharton and Codman also stressed the importance of a close relationship between architecture and interior design. Rather than remaining completely separate from architecture, interiors should reference the exteriors of buildings and the structures of spaces.

With the principle of simple and architecturally informed interior design, Wharton and Codman set off to write. The only problem: Wharton found that she “literally could not write in simple and precise English the ideas which seemed so clear in [her] mind.” She eventually overcame the challenge, and The Decoration of Houses met with great success—she later referred to this publication as “a touchstone of taste.”

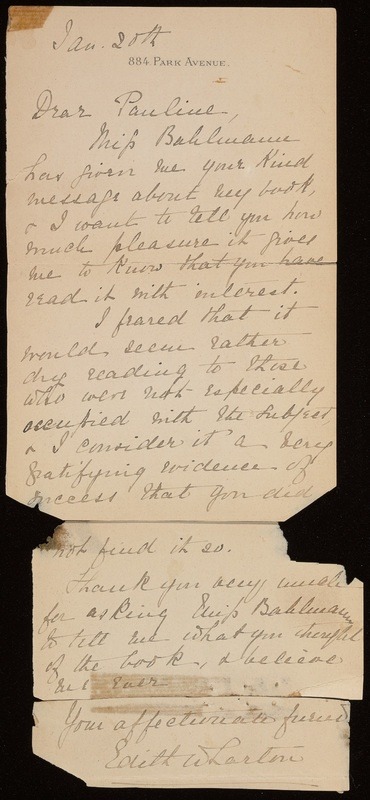

After the publication of The Decoration of Houses, Wharton received a message from a friend complimenting her work. Wharton responded in the letter below:

“…I want to tell you how much pleasure it gives me to know that you have read [The Decoration of Houses] with interest. I feared that it would seem rather dry reading to those who were not especially occupied with the subject and I consider it a very gratifying evidence of success that you did not find it so.”

. . . .

The Drawing Room

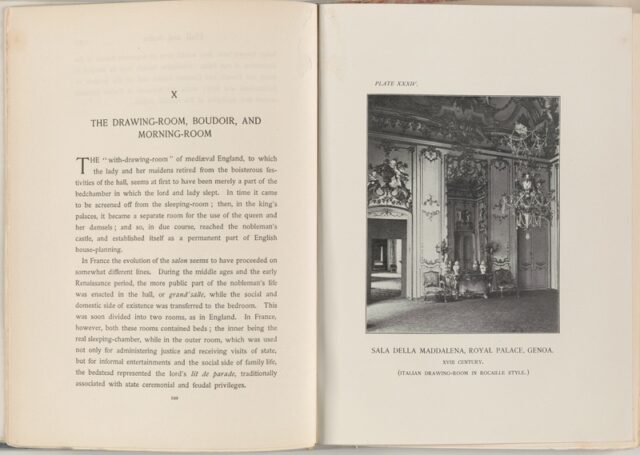

Wharton and Codman discuss the drawing room in a chapter titled “The Drawing-Room, the Boudoir, and Morning-Room.” These spaces are related through their association with women in Wharton’s society, but differ in terms of the level of privacy allowed. The drawing room could be both public and private, whereas the other two rooms were more personal.

In The Decoration of Houses, Wharton establishes the foundation of her understanding of the drawing room. The chapter begins by mentioning “the ‘with-drawing-room’ of mediæval England, to which the lady and her maidens retired from the boisterous festivities of the hall.”

The aristocratic European origin that Wharton and Codman identify for the drawing room applies also to the examples, shown below, that they reference throughout the book. Following the discussion of the room’s origins, this chapter charts the development of the drawing room through later examples into two distinct forms: the salon de famille and the salon de compagnie. The former was a more private space for family members and close acquaintances to gather in, whereas the latter was a more public, ceremonial space. Regardless of the type of drawing room, Wharton and Codman emphasize that comfortable, timeless furniture best suits this frequently occupied space.

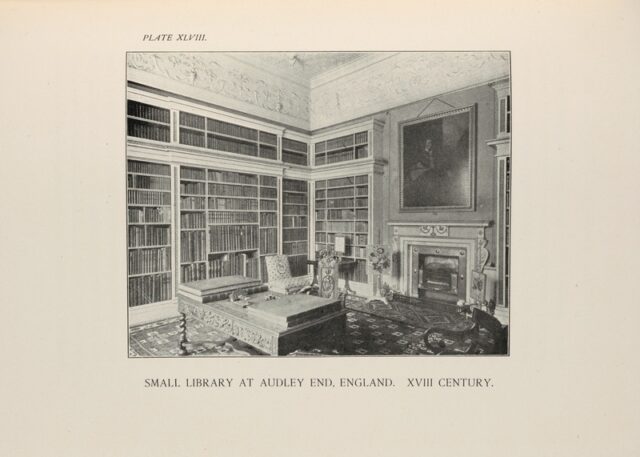

The drawing room is often discussed as a foil for the library: while the former was considered a women’s space in Wharton’s world, the latter was associated with men. The way that people in Wharton’s society used and moved through these spaces plays out in much of Wharton’s fiction, including The Age of Innocence.

Link to much more at Yale University Library Online Exhibitions