From Public Books:

In 1879, Alphonse Bertillon joined the Parisian police department. At the time, people who committed multiple crimes were having a good run of it—branding had been banned and fingerprinting had not yet been widely adopted. Officers’ memories, as Richard Farebrother and Julian Champkin have detailed, were the main remedy against repeat offenders, who gave false names, claimed it was their first offense, and were able to avoid serious consequences. The only alternative for 19th-century law enforcement: sifting through stacks of notecards cataloging prior arrests, which were completed idiosyncratically and organized haphazardly.

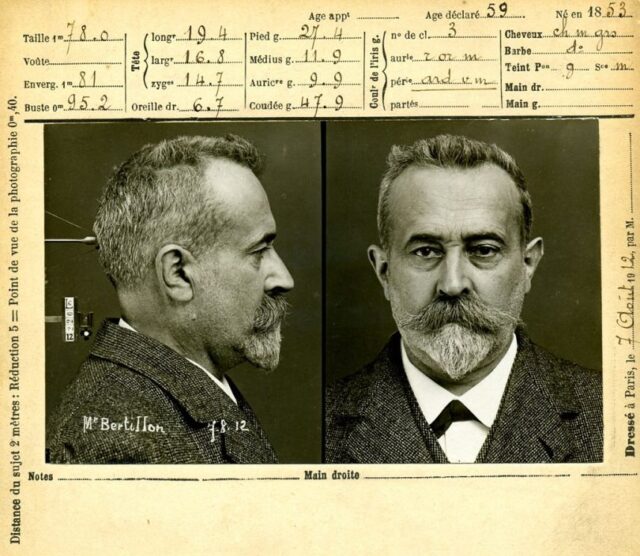

Struck by the system’s inefficiency, Bertillon created a cunning new method to identify alleged offenders. He envisioned “giving every human being an identity, an individuality that is certain, durable, invariable, always recognizable, and which can be established with ease.” Photography had just begun to arrive on the scene, and Bertillon recognized its potential for cataloging people who had been arrested. He pioneered the idea of seating accused people in the same chair, set a standard distance from the camera, and photographing them at standard angles. In so doing, Bertillon invented the mugshot.

More than a century later, face surveillance has gone digital. In January 2020, journalist Kashmir Hill revealed that a secretive start-up company called Clearview AI had scraped photographs from untold numbers of websites, collecting more than three billion pictures (now closer to 10 billion) to fuel face recognition technology used by law enforcement. The public was horrified. But the massive consentless collection of face data for carceral purposes is a foundational approach to face surveillance that originated with the two men who developed it, first as an analog technique and later as an automated technology.

As Bertillon’s story makes clear, the earliest applications of face surveillance were also not rooted in consent. Nearly 150 years ago, using images of faces to identify people who’d committed crimes was done without permission of those portrayed. Law enforcement officers were the primary users. And that tradition continued when Woodrow Wilson “Woody” Bledsoe automated face surveillance in the 1960s.

These essential flaws cannot be corrected with greater accuracy or oversight. Despite more than a century of time for potential introspection about face surveillance, it seems that law enforcement has not truly grappled with the collateral consequence of its expansion: the elimination of privacy for everyone. Instead, more law enforcement agencies are adopting face surveillance as you read this article. Face surveillance began as a carceral technology, and that application continues to ensure that the technology will be available, attractive, and financially advantageous to law enforcement and the companies who serve it.

Bertillon and Bledsoe’s work assumed that law enforcement personnel should have the power to surveil the faces of the people they were supposed to protect and serve. Today, law enforcement continues to buy into that belief. But Bertillon’s and Bledsoe’s stories reveal that face surveillance was flawed from the start and illustrate why those flaws persist.

Bertillon believed that “every measurement slowly reveals the workings of the criminal. Careful observation and patience will reveal the truth.” His approach, as Kelly Gates details, was not actually intended to reveal the inner workings of the individual—unlike physiognomy, an old, racist pseudoscience that postulated that certain facial features predicted criminality. Bertillon’s use of scientific measurement seemed a stunning development. He coupled his mugshots with intrusive measurements of people who had been arrested, such as their arm length and head circumference, to create measurements collectively known as a Bertillonage. He was assisted by Amelie Notar, a woman with impeccable handwriting whom he met crossing the road and who later became his wife.

It seemed improbable that an arrested person would share the same Bertillonage with any other person (though that assumption was ultimately proven wrong). Bertillon’s mathematical approach to identifying people who had allegedly committed crimes was popular and effective. Ultimately, Bertillonage identified more than 3,500 repeat offenders in its inaugural decade.

Bertillon himself became quite famous. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle referred to his own famed detective, Sherlock Holmes, as the “second highest expert in Europe”—after Bertillon, of course. But his methods proved fallible.

In 1903, a Black man named Will West arrived at the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. As was the standard procedure, identification clerks took his Bertillonage and matched the measurements with one William West. Police expressed no surprise that Will West was a repeat offender, nor that he denied being one. But upon investigation, Will West was discovered to be an entirely different man serving a life sentence for murder in the same penitentiary. The two men had identical measurements, something Bertillon and other police had believed impossible.

The fallibility of Bertillonage is among the least problematic aspects of Bertillon’s legacy. When he was not photographing people who had been arrested, Bertillon was writing a book called Ethnographie Moderne: Les Races Sauvages—translated, Modern Ethnography: The Savage Races. Bertillon also concocted a handwriting test used in the Dreyfus Affair, a now infamous case of government anti-Semitism. His participation in the trial spurred his brother, married to a Jewish woman, not to speak to him for years.

By the turn of the century, Bertillon’s “science” had been discredited. But the mugshot lived on. And it fueled generations of corporations, governments, and researchers curious about mathematically measuring the faces of people accused of committing crimes.

Link to the rest at Public Books