From The Wall Street Journal:

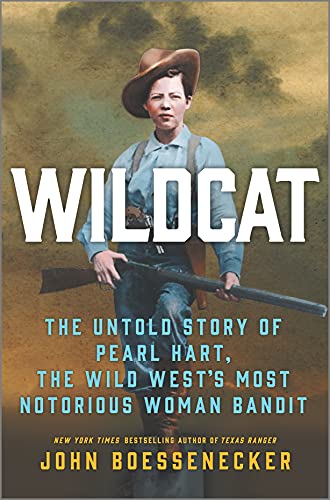

Near the end of “The Great Plains,” his classic 1931 study of the Anglo-American conquest of the nation’s midsection, historian Walter Prescott Webb acknowledged that, “since practically this whole study has been devoted to the men, [women] will receive scant attention here.” Much the same could be said even today about the genre of Western biography, in which books about famous men such as George Armstrong Custer, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and Sitting Bull proliferate, with relatively few volumes dedicated to exploring the lives of the region’s female characters. To be sure, figures like Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane have drawn their share of attention, but they are the exceptions that prove the rule. In “Wildcat,” the writer John Boessenecker offers for our examination the life of Pearl Hart, whom he deems “the Wild West’s most notorious woman bandit.” Alas, as a contribution to our understanding of the world of frontier women, it is a limited addition.

Mr. Boessenecker is ideally matched to his subject, having written 10 previous books, all with western settings, most focusing on outlaws and their badge-wearing pursuers. His subjects run from Tiburcio Vásquez, a 19th-century California bandido, to Frank Hamer, the Texas Ranger who—with help from other officers of the law—killed Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow in 1934. As with those earlier efforts, Mr. Boessenecker proves a tenacious researcher, with a particular knack for coaxing telling details from newspaper archives. For “Wildcat,” he also turned amateur genealogist and enlisted the help of one of Hart’s descendants, who shared with him extensive primary source material. “So in these pages,” he asserts, “appears for the first time the true and untold story of Pearl Hart, minus the falsehoods and folklore.”

She was born Lillie Naomi Davy in 1871 in Lindsay,Ontario, about 80 miles northeast of Toronto, and along with her eight siblings endured a chaotic and unstable childhood thanks to an alcoholic and abusive father, a man who served time for—among other offenses—the attempted rape, at knifepoint, of a teenage girl. One of the book’s strengths is Mr. Boessenecker’s obvious compassion for the plight of Lillie and her brothers and sisters. Lillie first ran afoul of the law at the age of 11, when she and an older brother stole a cow—twice—and sold it—twice—to unsuspecting buyers. Thereafter, she bounced around the Lake Ontario borderlands, and in Rochester, N.Y., married the first of her several husbands at age 16. She supported herself in part as a prostitute, and spent periods in correctional facilities in the United States and Canada.

With her sister Katy, Davy drifted westward through the Great Lakes during the early 1890s, known now by her alias, which was an homage to a prominent Buffalo madam. She reached Arizona in 1893, and soon fell in with a series of poorly chosen boyfriends while developing addictions to opium and morphine, indications of the poor judgment that led her and a partner, a shadowy figure named Joe Boot, to hold up a stagecoach in the scrublands between Phoenix and Tucson in late May 1899. As Pearl recalled, “Joe drew a forty-five, and said, ‘Throw up your hands!’ I drew my little thirty-eight and likewise covered the occupants of the stage . . . They were a badly scared outfit. I learned how easily a job of this kind could be done.” All the same, their haul was meager: $469 and a half-dozen six-shooters.

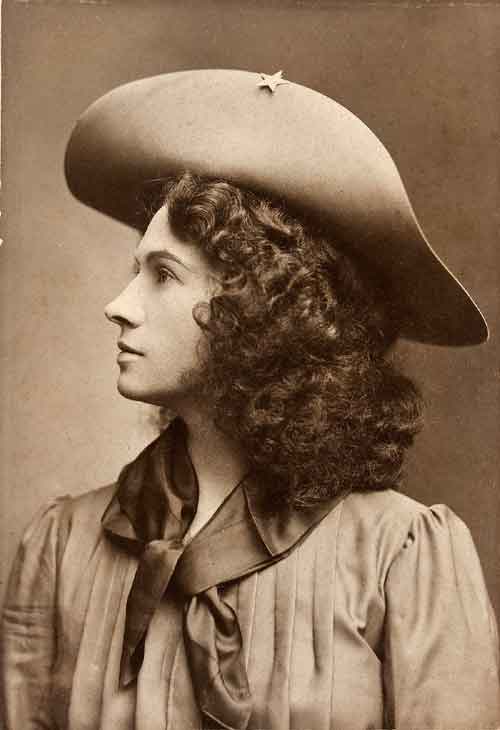

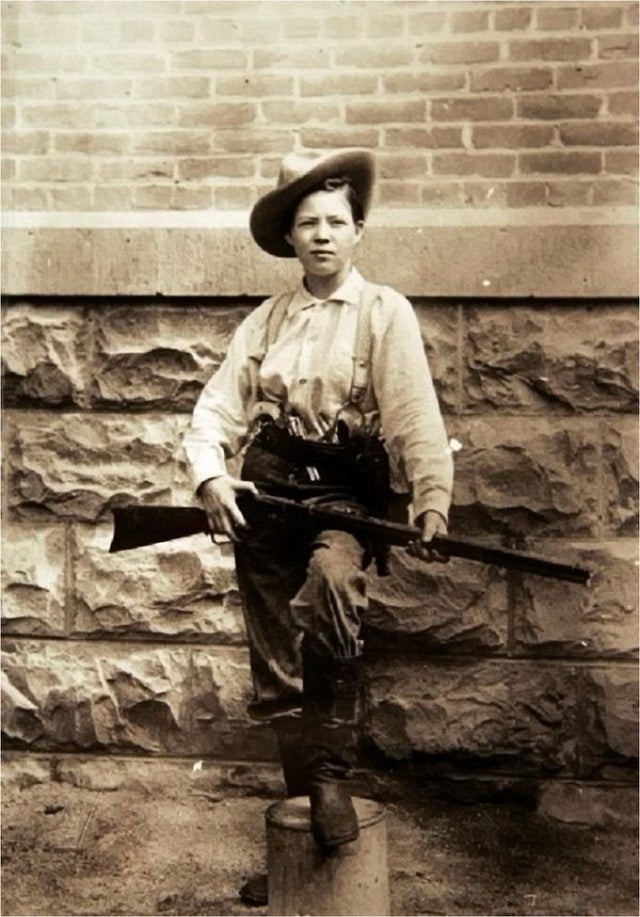

The pair was quickly apprehended and Pearl was soon confined to the Tucson jail, where her status as the sole female inmate—not to mention her affinity for men’s clothes—attracted the curious, including two locals who were recruited to interview her for a profile that ran in Cosmopolitan. The pictures that accompanied the article caused a national sensation: “In two photos she held her pet wildcat; in others she carried firearms . . . The public was simultaneously fascinated and shocked at the sight of a woman dressed like a cowboy and armed to the teeth.” In time she was relocated to the grim territorial prison at Yuma, but ultimately released in December 1902 thanks to a gubernatorial pardon. In later years she worked as an actress and tobacconist before slipping into relative obscurity. She died in Los Angeles in 1935, at age 64.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)

Hmm. Somehow I always thought Belle Starr was the most notorious.

She had a better publicist but she didn’t outlive her career:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belle_Starr

Outlaw notoriety is its own “reward”. 😀

Boessenecker’s biography of Frank Hamer, which you mention, is a great read. I’ll be glad to read Wildcat as well. Thank you for mentioning it, as I was not aware of it.

I love numbers.

The bit about the return of the stagecoach robbery being meager caught my attention: it ignores the economics of the time. $469 in 1899 is worth $15,500.17 today. Even for two people that’s a couple months’ living expenses. It was probably the most money either had seen at once. And the guns were worth fair coin too, a couple of dollars each then, around a hundred today. Folks robbed stage coaches then for tbe same reason they rob banks today: it’s where the money is. 😀

(Dollar a day wages were common at the time. Even in 1913, two dollars a day were common, even in the big industrial cities:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2012/03/04/the-story-of-henry-fords-5-a-day-wages-its-not-what-you-think/?sh=8136614766d2)

The other interesting thing is tbe date: essentially 20th century. Most wild west narratives focus on the post-war era and forget the west was wild all the way into the WWI years. Arizona and New Mexico didn’t become states until 1912. And then there was the Columbus Raid in 1916.