From Writer Beware:

That’s right, boys and girls–it’s another of my posts about hinky contest rules.

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you’ll know I publish a lot of these. That’s not because I like repeating myself…it’s because bad contest legalese is depressingly common, especially in contests conducted by high-profile organizations or individuals, such as HBO’s “Lovecraft Country” short story contest, or T.A. Barron’s Once Upon a Villain flash fiction contest, or the Sunday Times/Audible Short story award, or any number of others. Because it’s so common, though, it never hurts to put out another warning….especially when a contest offers the kind of prize money that’s sure to attract droves of writers.

In a twist, though, I’m not just going to talk about greedy legalese, but also about how one contest sponsor responded to criticism and made it better.

The Medium Writers Challenge is an especially rich contest, with a $50,000 grand prize, $10,000 for four finalists (one of the finalists will be the grand prize winner, so one person will actually win $60,000), and 100 honorable mentions who will each receive $100.

. . . .

To enter, writers choose a prompt, create an essay of 500 words or more, and publish it on Medium. A prestigious slate of judges that includes such luminaries as Roxane Gay and Natalie Portman will select four finalists, one for each prompt, and then choose the grand prize winner and the honorable mentions. The deadline to enter is August 24, 2021.

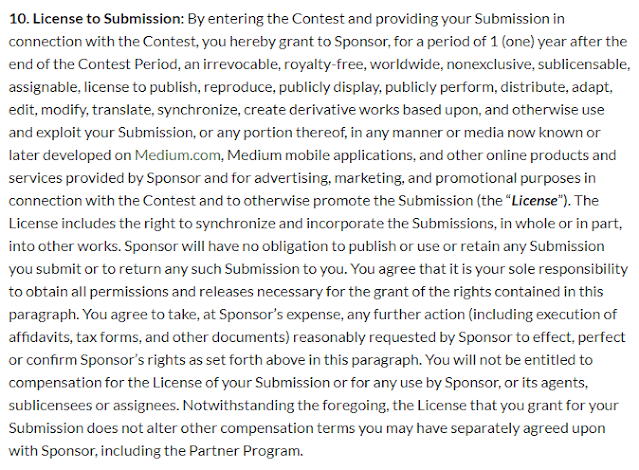

Moving on to the fine print, namely this paragraph of the official rules:

The concern was with the license writers grant simply by entering the contest, the wording of which gives Medium “an irrevocable, royalty-free, worldwide, nonexclusive, sublicensable, assignable” license to do pretty much anything it wants with any entry, whether or not it’s a winning entry.

This kind of language is extremely common, especially, as I’ve mentioned, in high-profile contests. The intent isn’t so much a nefarious scheme to steal writers’ rights or bind them to eternal servitude, as it is a shortcut for contest sponsors, who don’t have to fuss around with contracts for winners because they’ve already agreed to terms. It’s very easy to mitigate such language–for instance, by releasing non-winning entrants from the license once the winners are declared–but, carelessly or lazily or just sharkily, depending on how many lawyers formulated the rules, many contest sponsors don’t bother, even though it means that they retain rights they likely have no interest in and no intention of ever using.

In Medium’s case, though, they did take steps to mitigate. Note the second line of the paragraph, which limits the license to one year from the end of the contest period (presumably that’s the August 24 deadline). In other words, this is not the perpetual license that some other contests demand: it has an endpoint, after which it expires.

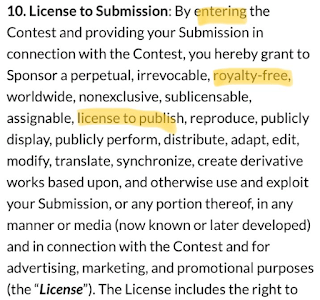

Here’s the interesting thing, though. Paragraph 10 didn’t always read the way it does now. This is the original version, the one that got people upset:

Note the difference: there’s no limit on the grant period. In this version of the contest rules, the license really is perpetual.

Link to the rest at Writer Beware®

In PG’s experience with large organizations, ignorance or stupidity can be just as destructive as evil intent.

If we rule out evil intent on the part of Medium (which seems to be the case if you read the entire OP), we’re left with ignorance and stupidity. These two characteristics can cause problems either individually or in conjunction with each other.

Drawing on his study of human nature, here’s how PG thinks this mess probably went down:

- Somebody in editorial at Medium could see that the publication would be short on content at some time within the next few months. Perhaps no one could think of new story ideas or maybe the business owners had cut back on budgets for commissioned articles so the cupboard was rapidly becoming bare. Staff writers had been squeezed dry and had no more good writing in them for awhile (or maybe they were fired, if they ever existed).

- The inevitable question followed: “Where can we get content for nothing?”

- One of the stock answers: “Let’s hold a writing contest and we’ll feature the winning entries in next month’s issue!”

- Scramble time.

- “Suzie, think up a theme and draft two or three good paragraphs about the contest. Run them past a couple of other people for quick takes. Make it sound sexy, cool and current.”

- “Bob, organize the summer interns to screen the entries and forward anything decent to you. I know you’re going to have to hold their hands, but that’s why you run the interns.”

- “Prizes! Hercule, figure out some cool prizes, but remember the budget. The main prize is being published.”

- “Thanks for reminding me, Heloise, we need to have rules. Go look for our last contest and use those. If we didn’t have a last contest, use Google to find some rules online.”

- “OK, team, you know what to do. Get going!”

See? No sign of ill will towards authors in sight.

Unfortunately, when the author of one of the submissions (they came in third in the contest) wins the Nobel Prize for Literature and another submitter hits the New York Times bestseller list, even though the summer interns are long gone, somebody at Medium will remember the names, look back and decide there’s a book there – “Famous Entries to Our Contest from People Who Made It Big!”

Unfortunately, one of the published entries is a seriously steamy piece by a best-selling Christian author who has since turned her life around and headed in the opposite direction without looking back.

In conclusion: READ THE FINE PRINT, EVERY BIT OF IT!

If you’re too busy to read the fine print and figure out what it means, don’t enter the contest.

To enter, writers choose a prompt, create an essay of 500 words or more,

“Choose a prompt?” What does that mean?

Sounds like they have a list. (Haven’t checked, not interested.)