From The Wall Street Journal:

Earlier this year, the police in Eugene, Ore., said they had identified a serial killer who committed three murders from 1986 to 1988. The man, John Charles Bolsinger, had escaped attention so thoroughly for three decades because he had killed himself in 1988.

Investigators had stored DNA from the crimes, and recently plugged it into a genealogy database, zeroing in on Bolsinger by first finding his distant cousins. It is the latest in a growing string of cold cases solved by law enforcement using techniques developed by genealogy hobbyists. Take a DNA sample, identify a second cousin here, a third cousin there, and then use public records to reconstruct a killer’s family tree.

If you’re concerned about the privacy implications of this, you might think, “Well, I would never submit my DNA to one of those sites.”

Sounds reasonable? In fact, it is far too late to completely protect your genetic privacy via personal abstention. A brief exploration into the mathematics of genetics explains why it has become possible to track down killers—but also anyone—through distant relatives.

“If somebody wanted to use the skills of forensic genealogists to try to track you down through a third cousin, they could,” said Jennifer King, a privacy scholar at Stanford University.

To understand how exposed your genes potentially are, consider an obscure unit of measurement—the centiMorgan, or cM. (It is named for Thomas Hunt Morgan, whose experiments on fruit flies led to the Nobel Prize in 1933 for showing how chromosomes are inherited.) It lies at the heart of all the stories you read nowadays of people discovering unknown links through their DNA and genealogical research.

It gauges genetic distance, specifically the length of identical segments of DNA that two people share due to descent from a common ancestor.

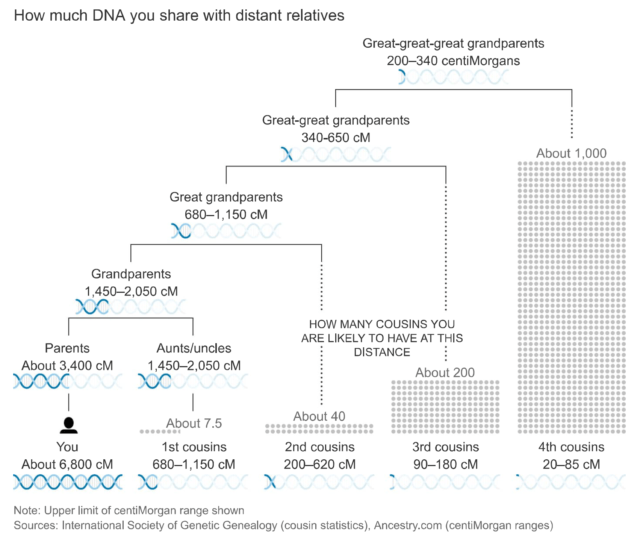

In general, people have about 6,800 cMs. A child inherits half their DNA—one set of chromosomes—from each biological parent. So child and parent will have around 3,400 cMs of DNA that match.

(Because of slightly different methodologies, the major testing companies report slightly different numbers.)

For every “degree of relatedness,” the length of shared cMs halves. An uncle or grandparent, one degree removed from parents, shares half as much DNA on average. That is 25%, or about 1,700 cMs. One more degree removed: A first cousin or great-grandparent shares half again, or around 850 cMs. And so on.

How much DNA you share with distant relatives

Even with all these halvings, very distant relatives out to fifth cousins share so much identical DNA that a common ancestor is the only possible source.

“I think most Americans don’t realize this,” said Libby Copeland, author of “The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.” “It’s a profound shift.”

It is easy to find distant relatives, because a typical individual has so many: according to various methods, around 200 third cousins, upward of 1,000 fourth cousins and anywhere from 5,000 to 15,000 fifth cousins.

This isn’t just relevant for crime scenes. There is no such thing anymore as truly anonymous sperm or egg donors, unknown fathers, or closed adoptions. They are all examples of scenarios where secrets involving parentage are easily solved by the centiMorgans. No court ruling or confidentiality agreement can erase this science.

An adopted child who doesn’t know his biological parent still shares 3,400 cMs with that person, and hundreds of centiMorgans with numerous cousins from that parent’s family. The child, or generations from now that child’s descendants, could upload their DNA to a database and by looking for matches with others who have uploaded theirs, discover some of those distant cousins. That would be enough to reconstruct his family tree and identify the parent, even though the parent never uploaded their DNA—the exact same process used to identify DNA in cold cases.

Katie Hasson, associate director of the Center for Genetics and Society, which advocates for protections against genetic information being abused, says that only collective action—not individual precaution—can address the privacy concerns this creates.

“Right now, forensic genealogy is very labor intensive and new, and being used for very serious crimes and cold cases,” said Ms. Hasson. “The likelihood it will be confined to that, without actual enforceable restrictions and regulations, is slim.”

The scale of testing is enormous: around 21 million samples on AncestryDNA, 12 million at 23andMe, 5.6 million at MyHeritage and 1.7 million at FamilyTreeDNA, according to data from the International Society of Genetic Genealogy.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)

This technique, at least in most cases, still only gives you a probability*. I would hope that even tech-savvy judges would require at least a bit more corroborating evidence before finding sufficient probable cause to issue an arrest warrant.

* Adding up the numbers given, assuming no duplicates between services, indicates that something around 10% of the population is “on file.” If you get as close as second cousins, that means you still have 36 potential suspects after the search tells you “close, but no cigar yet.” The pool only balloons at a greater distance – 180 at third cousins, 800 at fourth cousins, etc.

This does reduce the amount of LEO “legwork” required – but certainly does not eliminate it. (I hope that they had more than just this in fingering Bolsinger. Otherwise, there could be a killer wandering around out there that said “Huh, never knew I had a cousin John. Thanks for covering me, cuz!”)

For now it’s a starting point.

But 36 suspects (even 180) are manageable: alibis and can quickly whittle the list to a handful. Especially when the extended list is spread out cross coutry and not a KNIVES OUT scenario.

I have a problem with the whole concept, and do not trust large scale organizations to get things right, much less correct what they “believe” to be true when you point out that they are “wrong”.

I have lived in my house for 30 years. It was one of the first houses built in my Phase. I constantly have FedEx, UPS, the pizza guy, grocery delivery, etc…, coming to my house rather than to their intended destination, the house next door.

The house number is clearly posted on each garage, yet night or day, they come to my house and deliver stuff. They have done this since the beginning, I have always been here, the neighbors have changed out over time, yet I get the delivery, even though it is clearly labeled for someone else

– They are not actually looking at the house number, they are looking at their phone screen with Google Maps saying that this is their destination.

This clip from the movie Brazil is the perfect example.

Brazil (1985, Terry Gilliam) – Mistake? Haha. We don’t make mistakes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wzFmPFLIH5s

How many people will be “invited to assist the ministry of information with their inquires” when their DNA has been “suggested” to be the subject of that “inquiry”.

Yikes!

I think the WSJ had a How-To piece a few days ago on how to erase your house from Google Maps.

This was an issue in “The Great North Road” by Peter Hamilton. In it, a man was murdered in a strange way (the killer was an alien). The problem was that the man was a clone, and the question was: which of three clone-brothers was he descended from — helpfully their names started with A, B, and C — and which of the 100s in generation 2, 3, or 4 might he belong to?

Of course in that case, Brother C was living on a space station on one of Jupiter’s moons, and Brother B’s line usually lived on another colony around Sirius A/B, but as there’s “transporter” technology, that didn’t eliminate the possibility of someone visiting Earth and then being killed. Detectives had to lean hard on CCTV cameras and some future tech.

In the current day, the DNA “mugshot” won’t reveal if the person dyed their hair pink, was burned, or on the wrong-end of a knife fight, right? Or “had some work done.” Or, like that one politician who turned himself blue for some reason. I definitely would want to see more evidence in this case.

None of those tbings change the DNA. Which makes it more useful.

Relative and attribute matching narrows the field of suspects but real world convictions don’t rely solely on DNA. It *can* be the clincher, though. The new tech is an extension of the existing DNA tools.

Not to be forgotten: the DNA that was input into the system to start with can be tested against the fingered individual(s). It has to match. And in the real world we don’t have human clones yet.

Times change, tech evolves, and that applies to investigation as much as any other human endeavor. And rare though it might be, fingerprints can be erased:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lose-your-fingerprints/

DNA evidence fills in tbe gaps that might arise.

It might be worth revisiting the rise of fingerprinting. The case of the West Doppelgangers:

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/will-william-west-case-fingerprints/

And don’t forget the possibility of planting DNA evidence…the government (or individuals) would never do that, right? Oh, and police labs never make mistakes, mix up evidence, etc, right?

How often is it even worth worrying about?

DNA tests are faster tban they used to be but they’re neither easy nor cheap. They are used a lot less than TV makes it seem, even when there is good reason to.

For all the concern about police railroading people to “solve” a case, the real world issue is the opposite: lack of due dilligence.

Cold cases are legion. As are unprocessed rape kits:

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/08/an-epidemic-of-disbelief/592807/

Paranoia cuts deep, even if it is a survival trait.

A sense of perspective helps.

The man, John Charles Bolsinger, had escaped attention so thoroughly for three decades because he had killed himself in 1988.

Why does this concept make me think of this clip:

James Cagney in White Heat – Top of the World

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjzKiEs_pHI

It all goes into the Story folders.

Thanks…

Nice story.

But it’s only part of the story.

The bigger part is that as science gets better at understanding which genes are *associated* with specific trsits, especially physical ones, those stored DNA patterns encode more than relatives. They encode appearance:

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/24/science/building-face-and-a-case-on-dna.html

Already genetic sleuths can determine a suspect’s eye and hair color fairly accurately. It is also possible, or might soon be, to predict skin color, freckling, baldness, hair curliness, tooth shape and age.

Computers may eventually be able to match faces generated from DNA to those in a database of mug shots. Even if it does not immediately find the culprit, the genetic witness, so to speak, can be useful, researchers say.

“That at least narrows down the suspects,” said Susan Walsh, an assistant professor of biology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis who recently won a $1.1 million grant from the Department of Justice to develop such tools.

But forensic DNA phenotyping, as it is called, is also raising concerns. Some scientists question the accuracy of the technology, especially its ability to recreate facial images. Others say use of these techniques could exacerbate racial profiling among law enforcement agencies and infringe on privacy.

“This is another of these areas where the technology is ahead of the popular debate and discussion,” said Erin Murphy, a professor of law at New York University.

DNA, of course, has been used for more than two decades to hunt for suspects or to convict or exonerate people. But until now, that meant matching a suspect’s DNA to that found at the crime scene, or trying to find a match in a government database.

DNA phenotyping is different: an attempt to determine physical traits from genetic material left at the scene when no match is found in the conventional way. Though the science is still evolving, small companies like Parabon NanoLabs, which made the image in the South Carolina case, and Identitas have begun offering DNA phenotyping services to law enforcement agencies.

Illumina, the largest manufacturer of DNA sequencers, has just introduced a forensics product that can be used to predict some traits as well as to perform conventional DNA profiling. ”

“Now researchers are closing in on specific physical traits, like eye and hair color. A system called HIrisPlex, which was developed at Erasmus University MC Medical Center in the Netherlands, is about 94 percent accurate in determining if a person has blue or brown eyes, but less so with intermediate colors like green, said Dr. Walsh, who helped develop the technology.

HIrisPlex, which analyzes 24 genetic variants, is about 75 percent accurate for hair color, which can change as a person ages, she said.

Scientists look for genetic variants associated with physical traits the same way they look for genes that might cause disease: by studying the genomes of people with or without the trait or the disease, and looking for correlations. But this can be a complex task. ”

More at the source, including pretty pictures.

The NYT piece is 7 years old.

The tech is only getting better.

And TV writers have been using it for a while in shows “ripped from the headlines”. 😀

Excellent comment as usual, F.

I was in a group of about 30 men a few days ago and many had the free FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/) app on their smart phones.

The program has an option that allows you to see if you are related to anyone in the general vicinity (a few yards apart in this case) if they also have FamilySearch on their phones and turned on. (If you don’t want people checking out your ancestry, simply close the app on your phone/tablet

I quickly discovered that I was related to about a half-dozen of the other men. None were close relatives – typically the relationship information showed something like “7th cousin twice removed.” That meant we shared a common ancestor who had lived during the 14th century.

However, as the OP mentioned, someone who lived and was the mother/father of children who also married and had children, etc., has thousands and thousands of descendents. I’ve previously mentioned than it’s estimated that one in seven Americans is descended from someone who came to this country on the Mayflower and landed on November 11, 1620.

The latter fact was played for fun in a 1973 short story by Theodore R. Cogswell, “Probability Zero! The Population Implosion” as a tongue in cheek rebutal to the 60’s Malthusian fiction fad (and the CLUB OF ROME fallacious study that spawned it). Some were genuinely good (STAND ON ZANZIBAR, for one) but like most post apocalyptic dystopias, the fad died out of its own weight.

(The story treated all the ancestors in genealogy trees as being different people to show mankind was facing a tbousand year crisis that had reduced the world’s population from 100 billion ancestors to less than 4 Billion. So it behooved everybody to go and start making babies. Or at least practice. 😀 )

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?94197

If he were writing it today the hyperventilated crisis would be about the moon falling out of orbit or the sun going dark. The field has a long tradition of parody scientific reports.