From Publishers Weekly:

(PG Note – The author is a Slovenian publisher)

Nowadays, when everything is just a click away, people around the world have come to expect the latest installment of great TV series such as The Handmaid’s Tale or Game of Thrones to be delivered to their screens more or less simultaneously with the original release, together with corresponding subtitles in Croatian, Macedonian, Serbian, Slovenian…. There are many people involved with the production, and the security risks are extremely high, but still—the magic happens.

It is therefore somewhat surprising that in book publishing we’re witnessing a discriminating practice that has become increasingly common in recent years. In fact, this is now a sort of a status symbol, which divides major from merely big or important authors. At my Slovenian publishing company, Mladinska Knjiga, we still receive Mr. Barnes’s or Mrs. Hawkins’s or Mr. McEwan’s or Mr. Nesbø’s or Mr. Walliams’s new novels way ahead of publication (Mr. Nesbø even kindly provides the complete English translation for those who are not translating from Norwegian!), whereas this is not the case with authors (brands?) such as Dan Brown, John Green, or J.K. Rowling. Even Harper Lee’s second novel, Go Set a Watchman, was strictly embargoed until publication of the English edition. And now Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments faces the same issue.

The reason given is always the same: security. We were told by Atwood’s agency: “If this manuscript leaks, the consequences are huge, and therefore we have to have a strategy that minimizes the risk.”

A strategy? Some (well, most) of us are obviously not trustworthy. But there’s more. Initially a universal practice, this “strategy” is not without exceptions now. For example, the German version of The Testaments is scheduled for simultaneous publication with the original—so is the Spanish one and the Italian one. Is this then just a variation on a good old theme of “paying more” ? (One wonders how much of this is known to authors themselves, all fine people, who are usually sincerely grateful to each of their publishers from all around the world.)

The Booker shortlist was just announced, and it includes The Testaments. This is great news. It means that the book is good. But what it also means is that the jurors were given the manuscript ahead of publication, too. How did security procedures work in this case? I would rather not speculate, but let me just say that this only made us even more furious.

. . . .

In the case of The Testaments, we were particularly disappointed because we had initially been promised the manuscript in March (just enough time to publish more or less simultaneously), only to later be told that we’ll have to wait until September 12.

Why is this so crucial? We will lose the global promotional momentum and lose face in the eyes of our readers, booksellers, and librarians: the book is published, so where’s the Slovenian version? Most of them will think that the publisher is rather sloppy and slow.

The bottom line: we will sell less. And this is as important for German publishers as it is for Slovenian, Slovakian, and Icelandic publishers. Literary bestsellers are extremely rare. Therefore, one must seize every selling opportunity, and publishing simultaneously with the original edition is an especially effective one.

Sure, there are those houses that will hire multiple translators to finish the translation in two weeks, enabling the hasty publisher to publish the book just in time for the Christmas season. But would you really want to see or read the result? Margaret Atwood is a very fine author, one of the best. Her books deserve a committed translator and proper editorial dedication. And this takes time. So here is another factor that speaks against this strategy—the author’s reputation is at stake.

Link to the rest at Publishers Weekly

PG suggests that large publishers are almost religiously attached to their superannuated ideas about how to promote and advertise the books they release. Based upon shared folklore that the world is breathlessly awaiting the next release from OldPub in New York, they believe that a relative handful of chosen bookstores and an exclusive review in The New York Times will move the sales needle like it did before most people buy books online and the Times print circulation is plummeting.

Passive Voice

The Catalan publisher of the Testament is also critical of the English language tradpublishers. The Catalan edition will come out later because the Spanish translation has to come out first. Further there are cases where the Catalan publishers get the manuscripts either 6 months later or not at all. Worse some titles can’t be published in Catalan because the foreign rights aren’t released

So there seems to be a bias towards regional/minority languages by Anglophone tradpublishers

xavier

Take a look at this…

https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/bookselling/article/81168-testaments-off-to-recordbreaing-start.html

The book has sold 125 thousand copies and they are hard at work printing 500 thousand more.

How much water did independent bookstores carry?

Sounds about right.

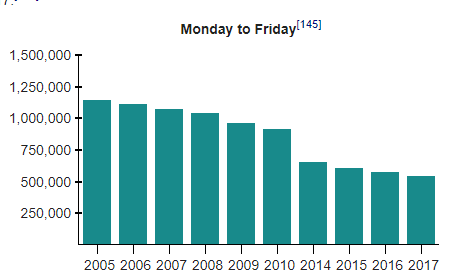

All non-chain stores combined add up to just under 5% of pbook sales. That’s why tradpubs mostly leave them for Ingram.

Amazon and the chains move over 85% of pbooks.

PG suggests that large publishers are almost religiously attached to their superannuated ideas about how to promote and advertise the books they release.

I see promotion and advertisement for paper towels, cars, TVs, and movies. I don’t look for it, but I see it. I don’t see anything for books.

Tradpubs do advertise: a few books a week, in the New York Times, the New Yorker, and a few NY-based literary jornals.

And tbey do promote: a week books at a time, usually by a big name legacy author, on a paid-for location in the front of B&N and a few other chains.

So it’s not zero. Just almost-zero.

And not affecting casual readers at all, who mostly come out to buy on buzz.

And when you consider the bulk of non-casual readers buy online…

But, hey! “It worked for granpappy.!”

Make that “a few books at a time”…

Two things. One is the fear the pirates will have the book out on the internet well before the publishing date (and piracy be the only way to obtain said book before the publishing date – and the preferred method of getting the book after the publishing date if it’s overpriced.) And two is if negative reviews get out before the ignorant buyers can buy the silly thing. (I think it was the over-hyped ‘Hulk’ movie that went from a block-buster success to a dud when the east coast warned the west coast not to bother with the thing.)

“And this takes time. So here is another factor that speaks against this strategy — the author’s reputation is at stake.”

Funny, but most publishers don’t seem to worry too much about the writer and are quick to drop them if their reputation might cause a problem.