From Electric Lit:

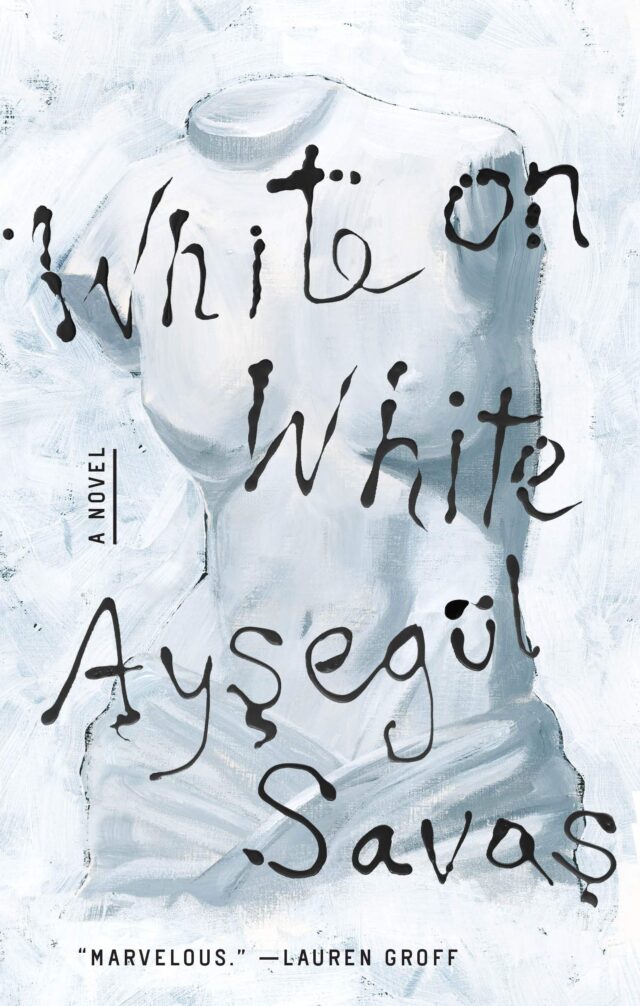

I loved Ayşegül Savaş’s first novel Walking on the Ceiling and have been pressing it into everyone’s hands for the past two years. I approached her second novel, White on White, with excitement and some trepidation, wondering whether I would love it as much. Well, the answer is yes. How exhilarating to be swept off my feet once more, torn between wanting to savor every sentence while also wishing to rush through to the end! Savaş’s writing is unadorned and yet perfectly attuned to the poetry and strangeness of everyday life. It surprises you with kernels of wisdom, such as “We make ghostly twins to carry the weight of our desires.” The world she describes is both recognizable and slightly off-balance, and nothing is ever what it seems at first glance. It is writing that I devoured in a few sittings and then returned to over and over again.

The premise of White on White is simple—a young student moves to a new city and becomes a confidant of sorts to the landlady, Agnes, a striking and magnetic artist, who very soon unsettles the narrator with her intimate monologues. Much of the novel is shaped by scenes in which the student listens to Agnes reflect on her art and recount memories of her marriage, children, and friendships with other women. At times I was reminded of Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima. Both narrators spend a year in a new apartment that is flooded with light. The passage of time feels hazy and is often marked by the change in seasons. There is an undercurrent of tension, barely perceptible at first, that intensifies throughout and makes it impossible to look away.

The excerpt below recounts Agnes’s years as a new mother and her relationship with her young au pair, beautifully exemplifying what I loved most about Savaş’s novel: the stories within stories, showing how what we remember from our past illuminates the way we see ourselves; the dissonance of memories within a family and how those breaks in understanding reveal an unwillingness or inability to see. At the end of this passage, the student feels that Agnes has “left out a part of the story.” One of the pleasures of reading White on White comes from exploring those omissions and being never quite sure what to believe. I reveled in this ambiguity: the constant shifts in perception, my expectations overthrown with each story.

Link to the rest at Electric Lit