From Book Riot:

While many book lovers would find it hard to not finish a book over the course of 365 days, this is the reality of over half of US adults. In a new study conducted by WordsRated, an international research and data group focused on reading and the publishing world, 48% of adults finished a whole book in the last year.

The American Reading Habits survey asked 2,003 American adults about their reading habits over the last year. This study was done as a means of offering a different perspective on reading than what’s typically offered via groups like PEW. Rather than define reading as a broad spectrum of activities, WordsRated had two criteria: the book must be print or digital (aka: no audiobooks, despite the fact audiobooks are indeed reading) and the book must have been finished in whole.

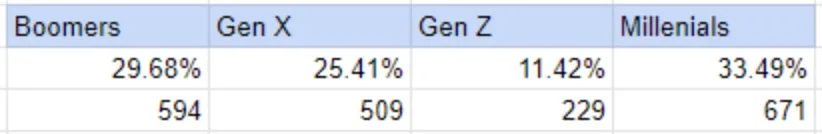

As seen above, those surveyed included roughly 30% of those in the baby boomer generation, 25% of those considered generation x, 34% of those considered millennial, and 11% of those considered generation z. The three largest groups of adults were roughly equal.

. . . .

While it is certainly surprising to see that nearly 52% of those polled did not finish a book in the last year, that 48% did is still pretty impressive. The act of finishing a book as the definition of reading here definitely gives a wholly different perspective–how many of those 52% include people who pick up a magazine or flip through a cookbook or try something and set it aside? How many listen to audiobooks exclusively?

. . . .

The data also show that a quarter of the same adults have not read a full book in 1 or 2 years, while 11% more have not read a book in 3-5 years.

A tenth of adults have not read a full book in the last 10 years.

Link to the rest at Book Riot

One of the reasons PG chose to excerpt this is the disconnect between the research group and the BookRiot people about whether listening to an audiobook is reading.

What do we think about that?

For PG (and, likely, almost everyone else), reading an ebook or paper book takes far less time than listening to an audiobook of the same same title. That might classify an audiobook listener as one who is more committed to spending time enjoying or learning from a book than someone doing the same thing as an ebook or on paper.

On the other hand, PG zones out while listening to the radio or music all the time and this almost never happens to him with an ebook or paper book. (If it does, PG will start a new book.)

This raises a couple of questions for PG:

- What’s the comprehension level for information taken into one’s brain via ebook/pbook vs. audiobook?

- Any difference in remembering what one has read between words on a screen/paper vs audio?

Many years ago, PG remembers reading that comprehension/understanding/remembering was better for a person reading from paper than on a screen. This was at a time when a screen was hooked to a computer and a keyboard, not a device like an iPad or smart phone.

In PG’s unscientific observation of himself, he doesn’t think that there is any difference in comprehension/attention for him regardless of whether he reads something on a screen of any sort vs. on paper. He does consume about 95% of the new information he encounters on a given day on some sort of screen and 5% (or maybe less) on paper.

Damn, yet another example that I’m a minority. I finished my first book of the year on 02 January, having gotten a good start during some noncompetitive football game broadcast windows.

Minority which way, C.E.? I’m reasonably sure that I finished a book on 01 January. I usually do, as after being up way too late the night before, I don’t have energy to do anything at all strenuous on New Year’s Day. (I stopped being at all interested in the games a long time ago.)

Minority in the “less than 50% have finished a book this year” per the OP.

I would have finished one on 01 January, but Reasons kept me from doing as much reading as I wanted to that day.

While I haven’t really picked up a book since Jan 2020 (public library closed for about 2 years), I still listen to a crap ton of podcasts, having discovered them in mid 2018. I think listening is the same thing as reading. I’m trying to get back into the swing of things with reading a book, but discovered that the time needed to properly enjoy a book is something I do not have anymore (thank you certain Asian country for ruining my life since 2020), so often I read in a max of 15 minute increments spread out over a couple of weeks. Haven’t done audio books since the downgrading of books on c.d.’s to simply being a niche market some 15+ years ago, but I still equate listening to a podcast to reading.

Hmm. I would equate podcasts more to listening to a radio show in years gone by. Just a different delivery method.

A couple of thought questions on whether “audiobooks” are “books.”

First – is a blind person (who has not been taught Braille, or does not have a Braille version available for what they want to consume) not a “reader”?

Second – and I don’t know about other people on this – I read by consuming text on paper or on a screen; I do not like audiobooks. But I “convert” that into “audio” in my brain. Would that not make the text into an “audiobook” in essence?

Opinion – Whether one “reads” by text or by audio is truly a personal preference, which should be neither lauded nor denigrated by someone with a different preference. Which preference may vary for some people depending on the text being read. Myself, I do prefer poetry when it is read by a good speaker – or “today’s Bible reading” when done by a good speaker, even when it is a prose section of the Book.

Oh, I would also note that some people can effectively multitask – “read” an audiobook, with complete comprehension, while doing other things. If only I were able to perform the same trick, I would have many more hours of productivity to show in other pursuits (theoretically, at least).

Is a performance of Shakespeare a play?

That then gets into “audiovisual” delivery.

Thing is, everything does get somewhat blurry – as, except for the very few people that can pull off ad-lib acting, everything starts as written text. (Or written musical notation, if you want to be liberal.)

As I noted, I classify audiobooks as “books,” since text is converted in my mind to audio. That audio, of course, is not what a narrator would provide – possibly inferior, although I do hear, say, female dialog in female voices, child dialog in child voices, etc. – which only the very best of voice actors can really provide in a recording.

I do much better with audio and listen to about 55 per year. I also read about 20 physical books per year. I don’t like reading on a screen. It’s hard on my eyes. For many of the articles PG links, I use a plug-in called Read Aloud or push to an app called Pocket where AI reads to me. I listen at faster speeds (same for podcasts) so I can consume a 75,000-word book in about three hours.

Reading is only one way to consume information. I’d suspect that most people comprehend better with reading in print or electronic but some do far better with audio. Since I need much of that audio for ghostwriting projects, I’d suggest my retention compares equally with physical reading. I love physical books but audio provides me the chance to consume much more than I would otherwise.

When my mother read Goodnight Moon to me in the late 1960s, I consumed it that way. And I retained it.

D – Your comment triggered a recollection of another study that found, essentially, that people could listen much faster than anyone can speak (and be understood). That’s not difficult to understand if someone is listening to recorded words rather than in-person where the brain is more fully immersed by facial expressions, gestures and individual mannerisms that are integrated with the words being spoken to understand the complete message.

I don’t do any public speaking any more, but, when I did a lot (invariably to groups of lawyers), I always preferred a setup that let me walk around rather than hiding behind a podium with a fixed microphone because it allowed me to communicate better because I could use my whole body.

Ditto for trial work. I hated it when a judge made the attorneys stand in one place instead of permitting them to move around. I particularly liked to get closer and closer to a witness I knew was lying to increase the pressure on him/her. (Yes, both genders lie and each gender includes good liars and bad liars. (I can’t speak to more genders than two because those were the only genders I interacted with back in the day.))

If my recollection is correct, speeding up a recorded human voice as you do doesn’t interfere with understanding of most listeners.

Correct.

Humans can easily understand audio at up to 210 words per minute (versus 105 in dictation) as long as pitch and volume are properly adjusted. This once hard process is now trivial with dozens of apps (most free) for Windows alone. Most of tbe better text-to-speech apps do it and many work with existing audio files, typically MP3s.

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/06/the-rise-of-speed-listening/396740/

Anybody interested in trying be sure to use an app with pitch control to prevent narrators sounding like ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS.

I don’t put much credence in any of these surveys.

The answers you get from surveys like these are a function of the questions you get and how you choose to interpret replies. You can (and usually do) get the answer you want.

In this case the first question I have (as always) is whether they distinguish between textbooks, catalogs, referencd books like legal and medical compendia, hardware and software manuals and, above all, The Bible (plus other religious books).

The last group is particular critical: 78% of the US reports as religious and in particular 35% identify as evangelical. So by asking about “reading a book at least in part” they are bound to get a lot of positives from the religious, as well college students and other professionals who read books as part of their jobs. Especially if they don’t clarify what kinds of book they are looking to pimp.

Meaningless.

(There is more to literacy than books in any form. Thst century is long gone.)

The one thing of (minor) significance is that unlike the typical book survey, they no longer exclude the ebook “fad”, only audiobooks (regardless of whether one may or not want them listed).

Now, this one is marginally interesting…

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/21/who-doesnt-read-books-in-america/

…even if it suffers the same definition faults as the other book surveys.

What I am seeing in those figures is hope for the future:

Gen X is only slightly less likely to read a book than the Baby Boomers; the Millennials are MORE likely to have finished a book in the last year. That’s encouraging, and something we need to build on.

The Gen Z is a young group, who may either not have BEGUN reading (the youngest are 2 years old), or are too busy with school-related reading to do it for pleasure. Once they become adults, they may be more inclined to pick up the habit, particularly if they find a genre that speaks to their interests. There are considerably fewer of them in the survey – about 1/3 fewer adults than other groups. Too small a group to make a sweeping assertion about their reading habits.

But, clearly, a significant portion of the population DOES read.

My response to reading that was – “Uh, no. That’s called listening.”

What a strange assertion.

I guess maybe they mean it is arguably equivalent in the sense that “all those words act on your brain and you comprehend something”?

I think it’s probably time for another study on how reading paper is superior to reading on a screen. Is the screen really reading?

I think you’re correct about another study being useful, E.

The one I referenced has to be quite old now.

I’m not qualified to give a definitive answer on listening to a book being the same as reading a book, but I can point out the confounding variables.

Listening involves someone speaking and the word rate will vary from say 100 to 200 words per minute; shmaaaybe (stolen from Craig Alanson’s Skippy character).

Reading depends on the literacy level of the reader and will generally be faster than talking. Perhaps a minimum of 150 words a minute, averaging around 350 to 450 words per minute, up to say 700 to 900 words per minute. Again, shmaaaybee!

What I can say with some authority is that learning modalities play a part. A learning modality is the sense input that a person favours: some will listener to the explanation, some have to visualize the solution, some are doers, some have to writer it out.

So when teaching ways to handle problems (basically the majority of mental health issues), the therapist has to match their teaching to the clients learning modality, with the caveat that the therapist ideally wants the client to learn using more than one modality.

TL;DR: It’s complicated.

Speed is certainly one thing. I read so much more quickly than someone can speak that impatience inevitably gets in the way of my enjoying an audiobook, as does keeping my attention if I attempt to multi-task with anything more complicated than driving a long distance. An audiobook is a performance like theater (or even real life), where pauses and timing are part of the show, and while I can read all day long, I can’t watch/hear a show all day long the same way.

Worse, I am one of those who actively hates getting important or complex information orally. I would much rather read something important than hear it. “In one ear and out the other” is just as true for me as “believing what I see with my own eyes”.

Book Riot’s assertion is gibberish: a classic example of “not even wrong.” Whether or not listening to an audiobook is “reading” is a matter of definition, not of fact. This is exactly as a statute begins with a section of definitions. These are not assertions of any great truth: merely clarifications of how the words are used in the rest of the statute. Book Riot uses a definition that includes listening to audiobooks. WordsRated used, at least in this study, a definition that excludes listening to audiobooks. Book Riot could have sensibly asserted that the study would have been more useful had it included them (or even better yet, split out the categories). But instead they went with looking foolish, not understanding the issue yet eager to opine on the subject.