From The New York Post:

Brooklyn federal prosecutors want an ancient artifact known as the “Gilgamesh Dream Tablet” returned to Iraq — where it was looted years ago before being sold to an unwitting Hobby Lobby for the arts and craft chain’s bible museum.

Brooklyn US Attorney Richard Donoghue’s office filed a civil action Monday asking that the $1,674,000 artifact, dating to 1600 BC, be handed over to the Iraqi government.

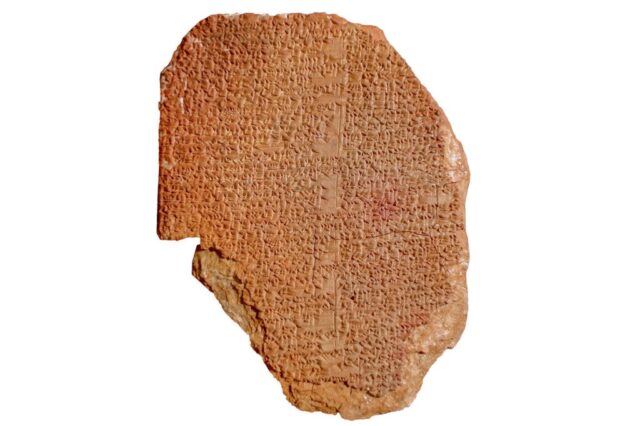

The Sumerian epic poem written in cuneiform on the clay tablet is considered one of the world’s oldest pieces of literature, officials said.

“Whenever looted cultural property is found in this country, the United States government will do all it can to preserve heritage by returning such artifacts where they belong,” said Donoghue in a statement.

“In this case, a major auction house failed to meet its obligations by minimizing its concerns that the provenance of an important Iraqi artifact was fabricated, and withheld from the buyer information that undermined the provenance’s reliability.”

Federal agents seized the 5-by-6-inch work in 2019 from the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC.

In April 2003, an unnamed antiquities dealer purchased the tablet along with a number of other items from another dealer in London, prosecutors said.

In 2007, that dealer sold the tablet for $50,000 to another buyer, and allegedly provided a fake provenance letter, falsely claiming it had been legitimately obtained at an auction in 1981 before laws were passed restricting the importation of Iraqi artifacts.

The tablet was later sold by an unnamed international auction house to Hobby Lobby Stores in 2014, in a private sale for an eye-popping $1,674,000 for display at the Museum of the Bible.

Three years later, a museum curator contacted the auction to clear up some contradictory information about the item’s origins.

Despite inquiries from the museum and Hobby Lobby, the auction house failed to disclose details about how they had obtained the artifact and withheld the false provenance letter, which it knew would not hold up to “scrutiny in a public auction,” prosecutors wrote in court papers.

It’s unclear whether the museum, which cooperated with the investigation, alerted federal authorities to the suspected theft.

The piece is known as the “Gilgamesh Dream Tablet” since it contains a portion of the poem in which the protagonist describes his dreams to his mother.

Hundreds of thousands of artifacts have been looted from archaeological sites throughout Iraq since the early 1990s and sold on the black market, officials said.

Spokeswoman Charlotte Clay said the museum fully supports the effort to return the tablet to Iraq.

“The museum, before displaying the item, informed the Embassy of Iraq on Nov. 13, 2017, that it had the item in its possession but extensive research would be required to establish provenance,” she said in a statement.

Link to the rest at The New York Post

Here’s what the tablet looks like:

Provenance: Important, Yes, But Often Incomplete and Often Enough, Wrong

From Artnet News:

This essay addresses provenance issues in the context of a sale. Of course the provenance of a piece is an important factor in determining its authenticity, but how important to the seller and buyer is knowing that, for example, there were three private owners between the artist and the current owner. If one of those owners was Paul Mellon or a major museum, it might be very important. And, have the buyer and seller made that importance clear in their sale agreement?

• • •

Ask anyone at the next gallery opening or museum exhibition and you will find nearly universal agreement that the provenance (lit. “origin”) of a work of art is important.1 In fact, a New York federal judge recently observed that “[i]t is a basic duty of any purchaser of an object d’art to examine the provenance for that piece…”

Less clear is whether the standards that exist in the art world about what should be included in the provenance are followed with any regularity or even can be followed as a practical matter. While theoretically intended to be a “chain of title” that should include every owner of the work since its creation, provenance typically tends to be a non-exclusive listing of interesting facts concerning the background of the work, such as notable former owners (at least those who are willing to have their identities disclosed) and the exhibition of the work at prestigious venues. Should galleries which held the work on consignment be listed? Does a seller have potential liability if the provenance provided to the buyer turns out to be inaccurate in any material respect? What if it is merely incomplete?

Before addressing those questions, it is useful to consider how provenance is relevant to sales of art. Art litigation generally falls within one of three categories: disputes concerning ownership, disputes concerning authenticity, and, to a lesser extent, disputes concerning value. The provenance of a work may bear on each of those potential areas of dispute. Obviously, to the extent provenance represents a chain of title, it may bear quite directly on a dispute concerning ownership. (If “H.W. Göring, Berlin” is listed in the provenance, that is probably a red flag).

More typically, provenance will be scrutinized where questions of authenticity arise. A few years back, an issue arose concerning the authenticity of a century-old sculpture attributed to a 20th-century artist of iconic stature. The work was sold to a prominent collector through an auction house with a certificate of authenticity from a qualified and appropriately-credentialed scholar of the artist’s work. According to the provenance provided at the time of sale, the work had been acquired in Paris after World War II by an art history professor from an Ivy League university. When questions of authenticity arose several years later, an Internet search and a few telephone calls to the university revealed that no such art history professor ever existed. Also left off the provenance was the fact that just months prior to the multi-million dollar sale to the prominent collector, the work had been purchased from an obscure antique store owned and operated by someone who had served jail time for art insurance fraud. Had these “errors and omissions” in the provenance been discovered at the time of the sale, the sale itself and several years of costly litigation would have been avoided.

Many works of art acknowledged to be authentic carry some risk that in the future questions of authenticity may arise. After all, experts sometimes change their minds, new experts may disagree with the old consensus, and new facts or technologies may emerge. An impeccable provenance that can be verified serves to mitigate that investment risk. On the other hand, we have seen that a dubious provenance may itself be used as circumstantial evidence that the work is a fake. Thus, even where authenticity is not currently an issue, an inaccurate or incomplete provenance still could give rise to a claim in the future.

Recently an art dealer faced a claim that the provenance he provided with a painting was incomplete because it did not include all of the owners going back to the artist. According to the disgruntled buyer, this omission was material because the provenance included a gallery involved in a well-publicized forgery scandal and, therefore, the painting would be hard to re-sell at an appropriate price without a verifiable provenance going back to the artist. Significantly, the painting had been sold at auction a decade earlier and the dealer had provided the current buyer with exactly the same pre-auction provenance as the prominent auction house had provided at the time of the auction sale. The dealer did not think to second-guess or investigate the completeness of the provenance provided by the auction house and did not have the resources to do so. Previous owners of the work did not want their identities disclosed due to privacy concerns (which is not uncommon), so a more complete provenance was not even feasible. Nevertheless, the buyer claimed that he had been promised a “verifiable provenance” and sought to revoke the sale. The buyer did not contend that the work was not an authentic painting by the famous artist, but merely that it would be hard to re-sell without a complete and verifiable provenance going back to the artist. Although the dispute ultimately was resolved without litigation, this episode starkly highlights the potential risks a seller may be assuming by providing—without qualification—a provenance that he or she has no real reason to doubt.

Link to the rest at Artnet News

Forging Papers to Sell Fake Art

From FBI News:

Michigan art dealer Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz grew up in a family of artists. His namesake uncle, Ian Hornak, was famous among Hyperrealist and Photorealist painters, and his mother was a gifted painter as well.

Spoutz became an artist in his own right—a con artist peddling fakes. His specialty was forging the paperwork that he used as proof of authenticity to sell bogus works.

His deceit finally caught up to him on February 16, when he was sentenced in New York to 41 months in prison on one count of wire fraud for defrauding art collectors of $1.45 million. The judge also ordered Spoutz, 34, of Mount Clemens, Michigan, to forfeit the $1.45 million and to pay $154,100 in restitution.

Spoutz’s scam was straightforward but well executed. He contacted art galleries or auction houses and offered for sale previously unknown works by artists such as American abstract impressionists Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Joan Mitchell. The art did not appear in any catalogs or collections of the artists’ known works, said Special Agent Christopher McKeogh from the FBI’s Art Crime Team in our New York Field Office.

“He was selling lower-level works by known artists,” explained McKeogh, who worked the case for more than three years with fellow agent Meridith Savona and forensic accountant Maria Font. “If it’s a direct copy of a real one, the real one is going to be out there and the fraud would be discovered.”

Before paying thousands of dollars for works of art, collectors and brokers want assurance the work is real—especially if the work is previously unknown, McKeogh said. Among other things, they look at the provenance—the paper history of an item that traces its ownership back to the original artist—for proof.

Spoutz, who also owned a legitimate art gallery, understood the value of provenance. He forged receipts, bills of sale, letters from dead attorneys, and other documents. Some of the letters dated back decades and looked authentic, referencing real people who worked at real galleries or law firms. Spoutz also used a vintage typewriter and old paper for his documentation.

The old typewriter turned out to be the smoking gun in the case. “We could tell all of these letters had been typed on the same typewriter,” McKeogh said. The type of a letter allegedly sent from a business in the 1950s matched the type in a letter allegedly sent by a firm in a different state three decades later. Spoutz also mistakenly added a ZIP Code to the letterhead of a firm on a letter dated four years before ZIP Codes were created.

Another red flag was that many of the people referenced in the letters were dead. And some of the addresses were in the middle of an intersection, or didn’t exist at all. “All these dead ends helped prove a fraud was being committed,” McKeogh said.

When marketing his fakes, Spoutz stopped just short of saying the works were authentic. “He tried to give himself an out and said they were ‘attributed to’ an artist,” McKeogh said.

. . . .

Spoutz produced the fake provenance, but not the fake art. “Spoutz was not known as an artist. He had a source he kept going back to,” McKeogh said. The FBI used experts in the field and artist foundations to determine the works Spoutz sold were forgeries.

Many of the fakes passed through auction houses in New York City, McKeogh said, and a suspicious victim eventually contacted the FBI. McKeogh inherited the case about three years ago, when another agent retired.

Although Spoutz has been sentenced, McKeogh and Savona do not believe they have seen the last of the fakes he peddled. The FBI recovered about 40 forgeries; there could be hundreds more that were sold to unsuspecting victims. “This is a case we’re going to be dealing with for years. Spoutz was a mill,” McKeogh said.

Link to the rest at FBI News

The OP’s are all dealing with the fringes of intellectual property, but, in each case, the original creator (or the individual creating the forgery) took something that had little to no intrinsic value — clay in the case of the Gilgamesh Dream Table, blank canvases in the case of the paintings — and added value to it

ironically, it it had been left in Iraq, it’s very possible that ISIS would have blown it up like they did so many other historical artifacts

Makes one wonder how long any of these artifacts can survive discovery. Was King Tut better off left in the dark for a few thousand more years?

Relevant – and a great read – https://www.amazon.com/Mormon-Murders-Story-Forgery-Deceit/dp/1250025893