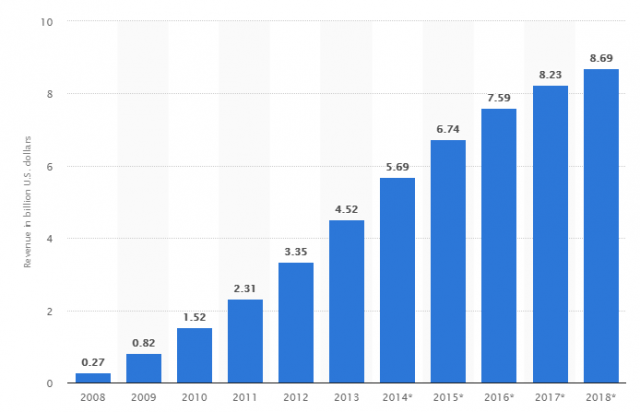

From Statista:

The timeline presents data on e-book sales revenue generated in the United States from 2008 to 2013, as well as a forecast until 2018. The source expects the revenue will grow from 2.31 billion in 2011 to 8.69 billion in 2018.

. . . .

In the United States, the e-books industry has grown tremendously in the past decade, primarily due to a higher supply and demand of e-book devices and applications, but also due to lower prices compared to hard copies, as well as ease of travel and storage. However, forecasts suggest that the number of e-book users in the U.S. is expected to fall from 92.64 million in 2015 to 88.45 million in 2021.

Many e-books are available through American public libraries, which, since 2003, have an increasingly popular e-book lending model of both fiction and non-fiction titles for different audiences.

Link to the rest at Statista

I find it odd that non-fiction doesn’t fare so well in digital. Search-ability and cross-referencing are most useful in non-fiction. I’ve been disappointed with the progress of eReading devices. I expected them to improve more and faster than they have. I would still be happy with my original Kindle if I hadn’t left on a plane seven or eight years ago. But I don’t think I would care to use a 10 year old laptop. If eReaders had evolved more rapidly, I think digital non-fiction would be much stronger. I find paper is still easier to navigate when the subject is complex. With the processing speed and storage available now, someone should be able to come up with something that would improve the experience.

BTW, I’m not sure I understand what you mean by “windowing.” Do you mean libraries are a distorted sample? I won’t argue with you there. If you mean some publishers avoid selling to libraries, I can only comment that when our acquisitions team decides the collection needs an item, they don’t hesitate to go outside the regular Ingram, B&T, etc. channels. (Often Amazon.) Without checking the numbers, I’d guess about a quarter of our book-buying budget goes directly to AMZN.

On the digital side, we are largely limited to what Rakuten offers us, which is a strangle hold that I would love to break, but so far, the grip just gets tighter.

Windowing is the practice of holding new releases from a specific channel to favor another.

Like movie studios giving movie theaters a three month (maximum, usually) exclusivity window before releasing the movie first to digital sales and disk saoes, then pay per view rentals, then premium video Channels like HBO, then ad-supported cable, etc.

Traditional publishing (except Ballentine, early on) windowed most mass market paperback releases to drive hardcover sales and in 2009 tried doing it with ebooks but the outcry and reduced sales meant they backtracked within three months.

They recently brought the concept back to libraries:

https://the-digital-reader.com/2018/07/19/tor-books-is-now-windowing-library-ebooks/

You *should* be seeing more pbook checkouts when the matching ebook is being withheld for up to 40 months so the only option is to check out the print edition. Especially with the high pricing of the Agency Part Deux ebooks.

Thanks. New vocabulary for me. There is a project that is studying the impact of libraries on book sales. https://www.panoramaproject.org/ They imply Macmillan is supplying data from the Tor windowing experiment among the project’s data sources. The project is a bit self-serving — the board has more librarians than publishers and initial funding is from Rakuten, but I’m waiting to see what they come up with.

My anecdotal experience is that library-users buy more books than non-library-users.

The consensus has long been that libraries bring exposure and help sales which is why so many Indies look for ways to try to be available in libraries.

Of course, Macmillan and Penguin (most notably among the BPHs) see libraries as a threat. Both have long been hostile to libraries. Not that the others are terribly friendly.

https://the-digital-reader.com/2011/11/21/penguin-ebooks-pulled-from-overdrive/

There really hasn’t been any progress in the utility of reading software. There is incredible potential for non-fiction, but I suspect it’s a minefield of copy and copyright issues.

If the non fiction is straight narrative, with little complexity, I’ll read an eBook. But the default is paper.

Imagine a simple application where one highlights a passage, clicks, and that passage is added to a separate file. Click another, and it gets added. Then print the separate file. Or read the separate file on the eReader.

This is just one simple, obvious feature. There are a zillion others.

An app like that exists.

It is called OneNote.

It’s free on several platforms.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsoft_OneNote

I know people who live their work lives in it.

It can aggregate, annotate, and organize, text, images, audio, video, pretty much everything. It understands voice as well as handwriting. It is probably one of the reasons Edge displays epubs and pdfs as.

I’m familiar with One Note. Can it operate through the Kindle, let one highlight, click once, and add the item to a One Note file?

The technology isn’t a problem. But, embedding that programming in eReader software seems to be lacking.

Adding to my wish list, I’d like to click and save a thumbnail in the margin. each thumbnail would be a link to a page in the book. Great for graphs, diagrams, tables. It could be modeled after all the #2 pencils I now stick in pages.

From my very narrow rural library knothole view, I see two trends: paper books are gaining. Slightly. Five years ago, ebooks were saving our circulation numbers. Paper was dropping, ebooks were soaring. Currently, paper is picking up, digital circulation continues to rise, but not soar.

My anecdotal experience is that both paper and digital have their places. People who live on screens grasp paper in relief from work. But digital is undeniably cheaper, more portable, lighter weight, more easily accommodates vision issues, and digital search-ability and cross-referencing is a boon.

I see more paper in the future than I once thought, but digital will continue to thrive.

The question with paper is: what kind of book?

With digital the answer is easy: narrative text. Mostly genre fiction.

Print? Not so simple. A lot of print categories have no viable digital equivalent. And with some publishers windowing libraries…

Gotta love mindless linear extrapolation.

Too bad the BPHs proceeded to flatline their own ebook sales right after the last measured point. Whatever portion of sales the BPHs contributed to the 2013 number has since declined, masking the growth from other publishers. And then there’s Kindle Unlimited and Scribd…

A proper extrapolation would have to factor in the technology adoption curve and the more or less artificial adoption explosion due to the shift in pricing models in 2010-2011. Which is to say the 2012-13 numbers were probably unsustainable to start with.

As a wag, I’d say realistic current numbers would probably show little growth from the projected 2014 number. Just a WAG, though.