From The Paris Review:

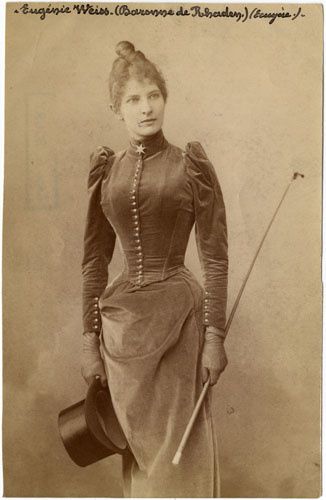

Most of the écuyères or horsewomen of the nineteenth-century circus left no trace of their own thoughts behind. Jenny de Rahden wrote a book. Whether she did it because she needed money or needed to put down her own side of the story after years of being spoken for in the European press—or both—is unknowable but she called it a roman or novel. I can’t tell how much of it is genuine. Jenny lived in an era before fact-checking and though her life was undoubtedly tragic, her style is sometimes melodramatic. “Does life really throw up these bizarreries, of which novelists and playwrights seem to possess the only secret?” she asks at one point. Perhaps calling it a novel gave her freedom to rewrite a messier past and fit it into more conventional romantic feminine tropes, rejecting the saltier stories written about circus horsewomen by male writers of the period. She was, after all, writing in 1902 when the century had barely turned and respectability remained a stifling life vest for women. She’d known its constrictions and buoyancy since birth: Jenny was not circus-born and she had become an artiste to support her father when he bankrupted them by gambling on the stock exchange. As a performer, her reputation as a lady was constantly at risk, not least because she supported not one but two men with her earnings. This dance around sex, money, masculinity, and respectability deformed her whole life—and resulted in a murder in her name.

Le Roman de l’Écuyère tells a familiar tale of a girl from a good family whose mother, as in the best fairy tales, died on hearing her first cries on a stormy night full of omens, and a father who, like Beauty’s, ruined the family with foolish business decisions. The good heroine refused to sell herself in a marriage that would restore the family, and instead bought three magical horses with the last gift her mother left her: an Arabian, a Trakehner, and the spotted Csárdás. Aged just seventeen, she took her father and her faithful aunt Tantante from Breslau (then part of the German Empire, now Wrocław in Poland) to Riga where a circus director and his jealous wife cheated her and stole one of her horses, and a distinguished gentleman at a local newspaper came to her aid like an excellent fairy godmother and ensured her success. On she went on a path through the woods peopled by circus directors who pinched wages, by their wives and daughters who did not want her above them on the bill, and by men who threw roses at Csárdás’s hoofs and rattled the door of her dressing room.

From Riga she went to Moscow, from Moscow to Saint Petersburg, where she was adored. One local aristocrat presented her with a huge golden stirrup as a tribute to her skill and charm. Another Baron asked the circus director, “Is there a way of doing something with the little one?” He was told that she was a good girl with a father and aunt in tow. He stared at her with such intensity that she fell off her horse, and of course he was there to scoop her up and take her home.

. . . .

In Copenhagen, a young Danish lieutenant called Frederick Castenschiold befriended both Jenny and the Baron but fell in love with Jenny. The Baron could not withstand the insult, and a duel was called. Jenny was told the men were going duck hunting. When she arrived in the aftermath, breathless from a performance and a train ride, dazzling circles vibrating before her eyes, she found her Baron bandaged with a Turk’s turban, smoking and laughing with his friends. Castenschiold was the army’s best fencer and her sailor husband preferred pistols—he had taken a saber swipe to the temple from the Dane. The matter resolved, they proceeded to the actual duck hunt. The Baron gave Castenschiold a photograph of Jenny. Castenschiold was reprimanded in person by King Christian for dueling over a circus performer.

. . . .

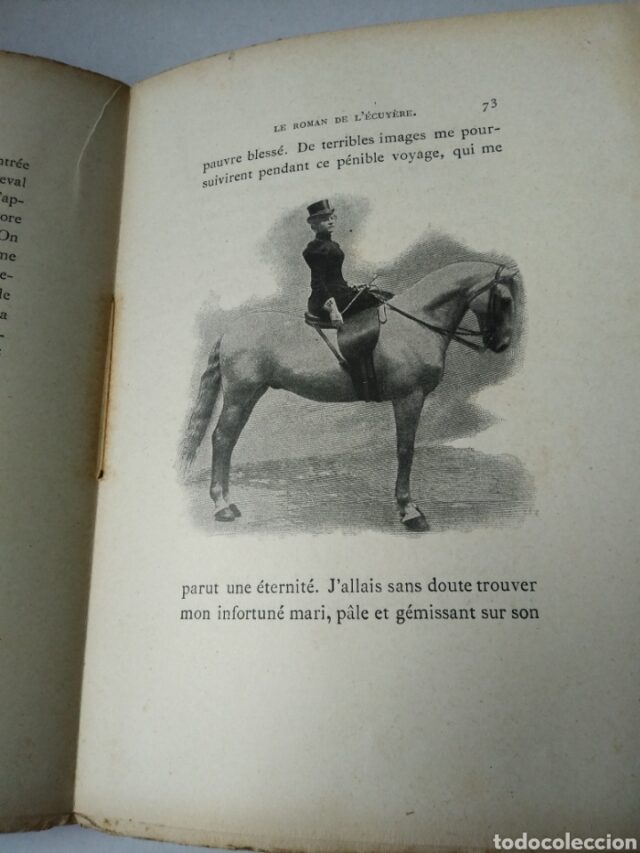

When Jenny first appeared at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris in October 1890, the critic and dramatist Jules Lemaître noted her conformation and that of Csárdás: “Very thin and very supple: a black thread; an elegant, dry little head, pale blonde hair tucked up under a top hat, with long kiss curls that cover half her cheeks and reach to the bottom of her ears, giving her pointy face a bizarre and disturbing air. She rides an equally bizarre big horse, pied as you’ve never seen before, riddled with ugly spots like ulcers, and which seems to be made of damp cardboard. She’s a Baudelairian horsewoman.”

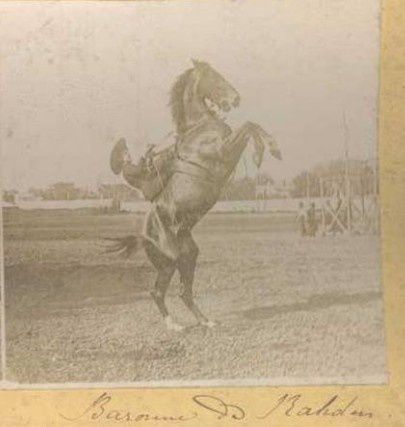

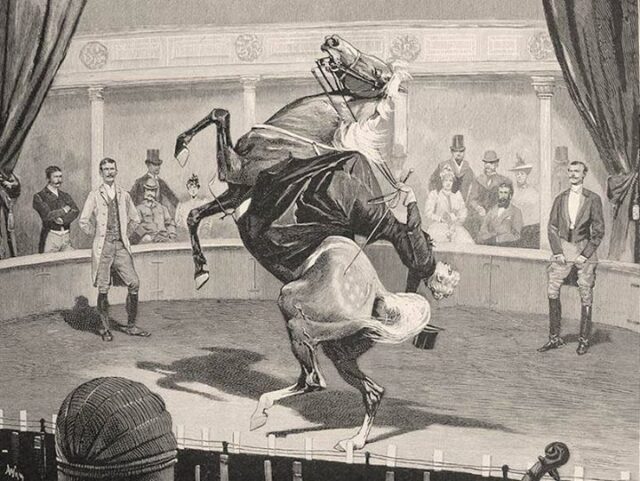

Lemaître could not look away. “I don’t know if what she does is difficult, but it’s very arresting. At one point, the horse rears straight up, and the slender horsewoman bends right over backwards and dangles her head low … She has a bizarre fashion of saluting too, a composite of a feminine curtsey and a masculine salute. Go see her. In short, she’s very fin de siècle. I don’t know exactly what that means, but that’s what she is.”

. . . .

In Turin in May, the Baron managed two duels in one day after a count sent Jenny love letters “in the language of Dante” and, peeved that she did not respond, brought friends to her next performance and blew a whistle throughout. The Baron slapped him; honor was demanded. The Baron slashed the count’s neck with a saber (the count survived), refreshed himself with some marsala, then tackled the count’s friend, the best fencer in Italy, who caught the Baron’s face and then, after “halt” was called, stabbed the Baron in the shoulder. The Baron throttled him and knocked him over. Nobody’s honor was satisfied, but the duels were at least over.

At Asti, another man threw white roses into the ring as Jenny performed, and her horse, startled, leapt into the audience and landed on an old lady, who had to be paid off from Jenny’s meager buffer against destitution. In Lisbon, there was a man who was sure he could perform Jenny’s best trick. He came to the circus with his wife and son, strapped a Mexican saddle to his horse so he would stick, and up he and his horse went in a rear and didn’t stop till they were both on their backs and his leg was broken. So then all of Lisbon was angry that their best “sportsman” had been injured by a woman’s circus trick.

. . . .

Madrid. Seville. On an afternoon’s outing, Jenny seized a man’s revolver and shot a runaway fighting bull that had disemboweled two mules and turned on her carriage. Malaga. Barcelona. Here, as Jenny joined the Circus Allegria, the Danish lieutenant Castenschiold reappeared like a bad penny, trailing tales of Monte Carlo debts and army discharges. He had been, he said, in Egypt and fighting rebels in the Sudan. He had no money and would like to work in a circus. When the Baron questioned him, he waved a knife at the Russian. The Baron turned his back, and the next day word in the circus said that Castenschiold had left for the Americas. He had not.

. . . .

August 23, 1890. Jenny was standing backstage beside her horse before her performance, the Baron at her shoulder, when Castenschiold materialized before them in the corridor that ran around the circus arena. The Baron, seeking to avoid what was barreling toward the three of them, turned and walked away around the curve of the corridor. Castenschiold spun on his heels and ran in the other direction, hurrying to meet him. They clashed. The Dane raised his stick and struck the Russian. The Russian drew his revolver and his fingers convulsed on the trigger. Jenny, buttoning her gloves, heard the two shots. Then two more.

She found the Dane bleeding on the floor, asking for someone to bring him two photographs—of his mother and of Jenny. The Baron walked past Jenny without seeing her. “Tell my wife I did my duty,” said his mustache, as he asked for an absinthe at the circus bar. The police took him into custody. Castenschiold died twenty hours later. In his rooms, they found a portrait of Jenny and a box containing unsigned letters from a woman, and more photographs of the Baronne de Rahden. In accordance with Castenschiold’s dying wish, this box was burned.

. . . .

The Paris papers sent their best men to cover the Baron’s trial, and when Jenny was fenced into another cramped space—the witness box—another story emerged in the questions the lawyers put to Jenny and her father. That tale splits away from the spare account of proceedings that Jenny the author later gave.

. . . .

Jenny stood with her teeth gritted, refusing to answer most of the questions posed to her:

“You perhaps encouraged Castenschiold a little to pursue you?”

She lowers her head without saying yes or no.

“The evening before the murder your husband hit you and your father.”

“I don’t remember.”

The Baron was unmoved. When the jury withdrew, the reporters saw her go to him, “with the moist eyes of a beaten dog that wants to be beaten again,” and say a few words in German to her grim, furious husband. He smiled.

The judge told him off for letting his wife risk her life in the circus. One reporter suggested that he was defending his meal ticket as much as his wife’s honor. But the Baron was deemed not guilty—this was self defense, not premeditated murder—and finally, his composure cracked and he cried. The women in the courtroom swooned at the romance of it. Jenny nearly collapsed; she had leapt out of the square of fences once again, but where had she landed? One reporter saw the Baron as he went to collect Jenny after the trial: “They remained silent for a moment; he always glacial; her frozen, cheeks scarlet, eyes shining.” As he took a step toward her, she backed up in fear and ran away weeping.

Who is being melodramatic here? Jenny, the landlady, or the court reporter? Jenny sums up the court case in a brief chapter of her memoir and does not mention the heliotrope dress or her own interrogation. She is a faithful, distressed wife willing the jury to set her husband free. One journalist notes that the Baron was the “defender of her glory and her virtue,” and “she loved him in that role.”

Link to the rest at The Paris Review

The Baroness reminds PG a bit of a woman he dated prior to meeting Mrs. PG. No horses or duels were involved, however.