From The Wall Street Journal:

Readers of history, like all readers, love an engrossing narrative: a conquest triumphant or repulsed, a great man brought to ruin by his flaws. The story doesn’t have to have heroes and villains, but it doesn’t hurt.

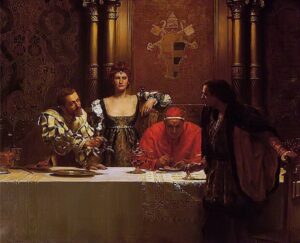

The intertwining chronicles of the Borgia and Medici dynasties offer rich material for such a narrative. Two of the wealthiest families in Renaissance Italy vied for supreme power, seizing thrones royal and ecclesiastic by force and cunning. The traditional version makes the Medici the heroes, philanthropic bankers who fostered the rise of humanism and science, commissioning masterpieces of art by Donatello, Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci. The villains, the Borgias, have become a byword of evil, covering the full gamut of the deadly sins, spiced with rumors of incest and occasional applications of poison.

Such history, when it is presented on the stage and screen—one thinks of Donizetti ’s opera “ Lucrezia Borgia, ” based upon a play by Victor Hugo, or of “The Borgias,” the TV series starring Jeremy Irons —can omit nuance and tailor facts as the story requires. But historians who seek a wide readership, while giving their readers the drama they crave, must honor the historical record in all its complexity.

Paul Strathern ’s “The Borgias: Power and Fortune” and Mary Hollingsworth ’s “The Family Medici: The Hidden History of the Medici Dynasty” (first published in 2018 and soon to be issued in paperback) present just such nuanced accounts. And they are not their authors’ first forays into the period, each having earlier staked a claim in the other’s dynasty, so to speak. In 2016, Mr. Strathern published “The Medici: Power, Money, and Ambition in the Italian Renaissance,” and Ms. Hollingsworth had previously published “The Borgias: History’s Most Notorious Dynasty” (2011). All four are fine books, authoritative and well-written, by independent scholars who know how to make the past come alive without turning it into pulp.

Both authors begin their Medici chronicles with a scene of high drama, then dial back to the beginning and progress chronologically, alternating between fully rendered scenes and brisk summaries. Mr. Strathern starts with the Pazzi conspiracy, one of the bloodiest passages in Italian history. In the late 15th century, the Medici ruled Florence as princes in all but name, led by young Lorenzo de’ Medici. In 1478, a rival clan, the Pazzi, plotted to seize control of the city. Mr. Strathern opens with a vivid scene of Lorenzo and his entourage riding to Mass. His younger brother, Giuliano, walks behind them, accompanied by his friends Bernardo Bandini and Francesco de’ Pazzi.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (Sorry if you encounter a paywall)

No love for the Sforza family? A mercenary working for the Duke of Milan, who ends up as the Duke of Milan himself. There’s a lesson to be learned there.