From The London Review of Books:

Nominally a book that covers the rough century between the invention of the telegraph in the 1840s and that of computing in the 1950s, The Chinese Typewriter is secretly a history of translation and empire, written language and modernity, misguided struggle and brutal intellectual defeat. The Chinese typewriter is ‘one of the most important and illustrative domains of Chinese techno-linguistic innovation in the 19th and 20th centuries … one of the most significant and misunderstood inventions in the history of modern information technology’, and ‘a historical lens of remarkable clarity through which to examine the social construction of technology, the technological construction of the social, and the fraught relationship between Chinese writing and global modernity’. It was where empires met.

. . . .

Long before it could be a technological reality, the Chinese typewriter was a famous non-object. In 1900, the San Francisco Examiner described a mythical Chinatown typewriter with a 12-foot keyboard and 5000 keys. The joke caught on, playing to Western conceptions of the Chinese language as incomprehensible, impractical and above all baroque: cartoons showed mandarins in flowing robes, clambering up and down staircases of keys or key-thumping in caverns. ‘After all,’ Thomas Mullaney writes, ‘if a Chinese typewriter is really the size of two ping-pong tables put together, need anything more be said about the deficiencies of the Chinese language?’ To many Western eyes, the characters were so exotic that they seemed to raise philosophical, rather than mechanical, questions. Technical concerns masqueraded as ‘irresolvable Zen kōans’: ‘What is Morse code without letters? What is a typewriter without keys?’ A Chinese typewriter was an oxymoron.

The earliest alphabetic typewriters were devised at a time when orthographic Darwinism was fashionable. In the 1850s, the naturalist Henry Noel Humphreys suggested that the Chinese ‘never carried the art of writing to its legitimate development in the creation of a perfect phonetic alphabet’. Bernhard Karlgren, in his Philology and Ancient China (1926), led a vanguard of alphabetic supremacists, arguing for the characters to be replaced with a phonetic system. Over the following decades, scholars would even suggest that the writing system, by depressing literacy, ‘inhibited the development of a democratic literate culture’. More recently, Derk Bodde and William Hannas have claimed that the Chinese writing system inhibits creativity and the capacity for independent thought. These are corollaries of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which holds, in its strongest forms, that language limits thought. A language incompatible with typewriter keys was incompatible with modernity, and bespoke an equally incompatible country.

. . . .

With the dominance of Remington’s single-shift machine over its competitors, index and double-keyboard typewriters that promised greater flexibility for non-Western languages faded from view. Decades of ‘minimal modification’ followed, reaching peak futility in the system adopted to send messages by telegraph, which required operators to familiarise themselves with 6800 characters assigned a code between 0001 and 9999, a task about as conducive to productivity as memorising pi. ‘Whether Morse code, braille, stenography, typewriting, Linotype, Monotype, punched-card memory, text-encoding, dot matrix printing, word processing, ASCII, personal computing, optical character recognition, digital typography, or a host of other examples from the past two centuries,’ Mullaney writes, ‘each of these systems was developed first with the Latin alphabet in mind, and only later “extended” to encompass non-Latin alphabets.’ For nearly two centuries, China had been a left-handed kid in a world of right-handed scissors.

. . . .

By the early 20th century, baihua, or ‘plain speech’, reformers were making arguments that recall Boulez’s line about having to set the Louvre on fire before civilisation can be freed. The founder of the Communist Party, Chen Duxiu, was among those calling for a ‘literary revolution’, a revolt against the ‘ornate, sycophantic literature of the aristocracy’ and in favour of the ‘plain, expressive literature of the people’. Baihuaproponents were also driven, at least in part, by frustration at decades of effort to reconcile Chinese characters and Western-derived systems. The early script reformer Qian Xuantong argued that the reform of systems had to begin with characters, ‘if we wish to get rid of the average person’s childish, naive and barbaric ways of thinking’.

. . . .

Unlike moveable type, which developed in China earlier and independently of the West, the typewriter has always been a foreign import. As such, its most successful inventors have tended to be boundary-walkers themselves, versed in both cultures if not entirely fluent in both scripts. The first machine marketed as a ‘Chinese typewriter’ was invented in 1888 by the American missionary Devello Sheffield, his goal less to create a typewriter than to replace the missionary’s intermediary, the opinionated Chinese clerk. ‘They usually talk to their writer,’ Sheffield wrote, ‘and he takes down with a pen what has been said, and later puts their work into Chinese literary style … The finished product will be found to have lost in this process no slight proportion of what the writer wished to say, and to have taken on quite as large a proportion of what the Chinese assistant contributed to the thought.’

. . . .

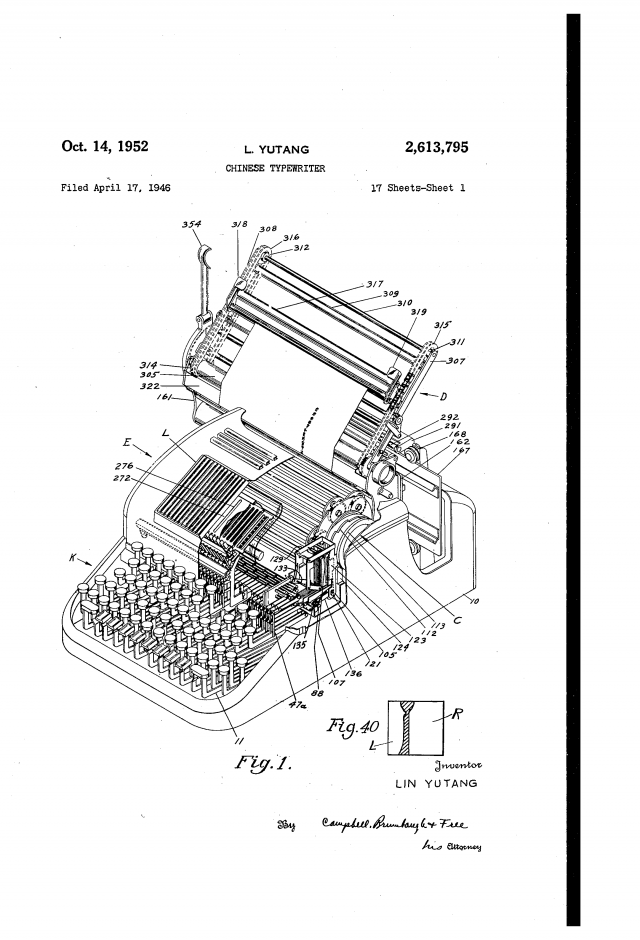

Part of the problem with these early typewriters is that they didn’t much resemble typewriters. The typewriter’s attraction was not only its usefulness, but its cultural cachet. One thinks of the famous image of Chinese dignitaries gathered around a Gatling gun. The point was being in a position to announce: ‘We have the technology!’ Inventors worried that if the typewriter were altered for the Chinese market, ‘the resulting machine [might] prove entirely illegible and unrecognisable to the Western eye … And if unrecognisable to the world as a typewriter, would it be a “typewriter” at all?’ And so it is unsurprising that engineer Shu Zhendong’s eminently typewriter-like typewriter was the first to be mass-manufactured. The Commercial Press in Shanghai, Republican China’s busiest printer, sold at least 100 units a year of ‘the Shu-style typewriter’ between 1917 and 1934 to customers as various as the Chinese Consulate in Canada and the Chinese postal service.

. . . .

Briefly, following Japan’s defeat, Chinese manufacturers were able to reclaim the market by selling copycat Wanneng machines, or even selling Wanneng machines directly, without pretensions to originality or patriotism. One Shanghai company sold a ‘People’s Welfare Typewriter’ – slapping a name borrowed from Sun Yat-sen on a Wanneng. The Communist government engaged in the same practices on a grander scale, seizing the Japanese Typewriter Company and rechristening it the Red Star Typewriter Company. In the 1950s, resistance to Japanese machines finally collapsed: the Shanghai Chinese Typewriter Manufacturers Association was created out of a consortium of ten Chinese typewriter companies – their enduring legacy would be the ‘Double Pigeon’, a sprightly Wanneng-based number that would dominate the market for decades to come.

Link to the rest at The London Review of Books

Here’s a link to The Chinese Typewriter

I recently visited Vietnam, which changed their alphabet to the Latin alphabet. Big difference in being able to read signs. But then I didn’t spend years and years learning the Chinese alphabet. The Vietnamese Latin alphabet writing was developed by a Portuguese missionary in the 16th century. It wasn’t until Ho Chi Ming in the 1950’s that changed the alphabet to the Latin writing, I was told. The reason was that the Western World used the Latin alphabet and that’s where business and technology was, which Vietnam needed. At least that was a smart move on his side.

Fascinating. Typing must be interesting on such a typewriter, and dependent on the typist.

Many language developments were made by missionaries – oral languages to some kind of a character-based written approximation, translations, dictionaries – but this one, of having the Chinese assistant tweak the meaning, hadn’t occurred to me.