From SCOTUSblog:

Today, the court’s attention will be on the often glamorous worlds of Pop Art, rock photography, and glossy magazines. It will veer into “Lord of the Rings,” “Jaws,” “Mork and Mindy,” and “The Jeffersons.” And one of the lawyers participating today will try to bury a beloved television producer and social activist. But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

. . . .

And then it is on to the argument in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith, a copyright dispute over a photograph of the musician Prince. Rock photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who took the photo of a vulnerable and sensitive-looking Prince in 1981, when he was still an up-and-coming musical artist, is in the second row of the public gallery today.

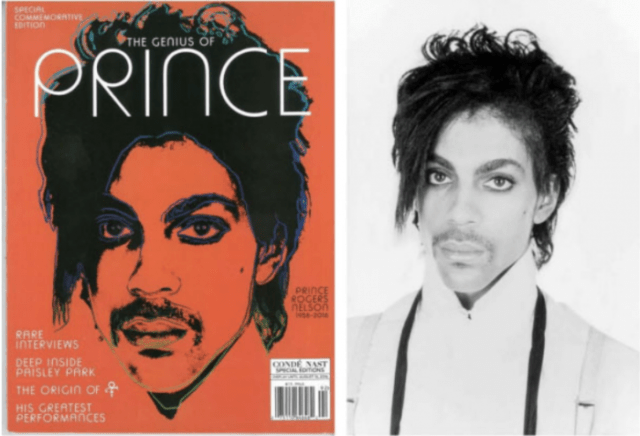

When Prince shot to stardom by 1984 with his “Purple Rain” album, Vanity Fair licensed Goldsmith’s photo for use as an artist’s reference for an illustration to accompany a profile of Prince. The artist they engaged was Andy Warhol, famous for his paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans and celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe.

Warhol cropped and silkscreened Goldsmith’s photo into a series of 16 images of Prince, now known as the Prince series. One of those — “Purple Prince” — ran with the Vanity Fair article. Another, “Orange Prince,” ran on the cover of a commemorative magazine that publisher Condé Nast issued after Prince’s death in 2016.

Goldsmith objected to the 2016 use as a violation of her copyright, though the New York City-based Andy Warhol Foundation filed suit pre-emptively to seek a declaration that the entire Prince series was a fair use under copyright law because, according to the foundation, Warhol’s images transformed Goldsmith’s photo into a new work with a different meaning or message.

Roman Martinez, representing the foundation, tells the court that “the stakes for artistic expression in this case are high. A ruling for Goldsmith would strip protection not just from the Prince series but from countless works of modern and contemporary art. It would make it illegal for artists, museums, galleries, and collectors to display, sell, profit from, maybe even possess a significant quantity of works. It would also chill the creation of new art by established and up-and-coming artists alike.”

Goldsmith is shaking her head as Martinez speaks. Throughout the argument, she will visibly show her disagreement or nod in agreement with various points made by the lawyers and justices. Elsewhere in the courtroom are several representatives of the foundation—President Joel Wachs, Chair Paul Wa, and Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer KC Maurer. I can’t see whether they are shaking their heads or not.

Link to the rest at SCOTUSblog

A more-qualified-than-any-of-the-current-justices commented, just about 120 years ago:

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251–52 (1903) (Holmes, J.) (citation omitted).

The less said about the contempt displayed by the editors of Vanity Fair and Mr Warhol for Ms Goldsmith’s photograph, the better. Neither “publicity” nor “the honor of being ‘appropriated’ by a Great Artist” matters here. As Justice Ginsburg noted a couple of decades ago concerning precisely those claims being made by yet another pillar of Establishment Publishing:

New York Times Co., Inc. v. Tasini, 533 U.S. 483, 497 n.6 (2001).

Whilst Justice Holmes was undoubtedly correct in his distaste for judges becoming art critics, does the burden placed on SCOTUS by the first factor in 17 U.S. Code § 107 leave them any choice? Or is this the result of the court choosing to take on this role when deciding earlier cases and developing the idea of the possibility of transformative uses of the copyrighted work?

I am no more qualified than a Justice of the Supreme Court to make artistic judgements but my feeling is that what is little more than a simplistic colour filter is being used to rip off the photgrapher, and that’s before taking into account the other three factors which definitely seem to favour Ms Goldsmith. But then I am not a lawyer and what seems obvious to a layman rarely convinces a court.

Mike, I think Justice Holmes’s point was that judges must be wary of imposing their own inexpert, restricted, more-Ivory-Towerish-than-any-academic, views on the “worth” of a creative work, specifically including whether what is in that work is “creative” or “original.” And in that sense, the fair-use aspects of this particular dispute should be evaded because there’s another ground on which this dispute can be resolved: Did whatever the Warhol Foundation (and Vanity Fair) “do” breach not copyright law, but the terms of the license agreement? One doesn’t reach any “artistic merit” or “originality” or “theory of transformative use”† question unless the examination of the license comes out a certain way (one of six distinct possibilities; the other five evade the fair-use question, one way or another).

On the other hand, I thoroughly agree that there is a duty to decide something here. (The decision not to decide is itself a decision. At times, that results in people like me, in my first career, meeting aircraft in Delaware and escorting the “cargo” to Robert E. Lee’s back 40…) I just don’t approve jumping to teh sexy copyright issue — if anything about copyright can come within a couple of miles of “teh sexy” — respects anything, including the copyright issue. And especially not in the context of “appropriation art” both “then” and “now,” and considering reuse of that “appropriation art” in ways not even contemplated by the parties to the license, and with multiple dead celebrities involved.

† With all due respect to the esteemed Judge Leval, he was operating outside of his expertise in formulating that theory. And it shows — not just in the overuniversality, but in the elision of “process” and “product.” Transformative use attempts to excuse “product defect” with “exemplary process”… and even the underlying description of “process” is not just overuniversalized, but a distinct minority view of creative process (even in the late 1980s and early 1990s when he was formulating the theory, before darned near anyone had heard of “remixes” and, more to the point, at a time that “parody” was considered not eligible for the fair use defense as a matter of law).

Transformative use is an important theory that deserves study as an intermediate model on the way from “ancient theory” to reality, analogous to the Bohr atom; it’s not fit for the purpose of actual work in the lab. Or on the canvas or printed page. The remaining text and 330 footnotes (so far) are for that law journal article that was interrupted by a 1500km move and surgery.