From The Wall Street Journal:

Today, when public language can seem slippery or unreliable, we might, for pleasure as well as reassurance, check in with the masters of English poetry. They may sometimes use gibberish, gobbledygook or balderdash for fun but, in the end, they leave us delighted rather than confused. Some kinds of nonsense are consoling.

Consider Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky.” For nearly 150 years, it has provoked happy squeals in children, and inspired serious analyses in lit-crit scholars. The poem comes from “Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There” (1871), the sequel to “Alice in Wonderland” (1865). Its origin goes further back. Stanza one appeared, in 1855, in “Mischmasch,” a periodical Carroll made for his family:

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

On its face, this may seem like nonsense, and in fact Alice herself has problems with it: “It’s very pretty, but it’s rather hard to understand.” She’s wrong. It may distort sense, but it is not nonsense. If you know English syntax and parts of speech, you know immediately that “toves” and “wabe,” like “borogroves” and “raths,” are nouns, even if you have no idea what else they are. “Gyre” and “gimble” are verbs, “mimsy” and “mome” adjectives. “Brillig” and “outgrabe” are ambiguous. In poetry, all words are important, and the odder they are, the more provocative.

. . . .

Carroll’s creatures, like his words, initially seem weird. But they, too, have meanings or insinuations, in context. Carroll tried to help (or perhaps to confuse) his reader. In the book, Humpty Dumpty offers Alice some definitions. He calls toves “something like badgers” but adds they are also like lizards, and like corkscrews. Carroll’s notes in “Mischmasch” have it a bit differently: A tove is “a species of Badger with smooth white hair, long hind legs and short horns like a stag” that lives “chiefly on cheese.”

Subsequent commentators have made their own interpretations. A variorum edition of the work (such as Martin Gardner’s “The Annotated Alice”) resembles a scholarly Bible or Talmud, with layers of commentary heaped on prior commentary, as one scholiast responds to another.

Is there an original truth? Or is the poem’s meaning the sum total of all the possible interpretations? Whom to believe? As Alice might say, “curiouser and curiouser.”

. . . .

“Snicker-snack” is delicious. And “Galumphing” and “chortled,” words of Carroll’s own invention, have entered our shared vocabulary. We have inherited his creations, the words as well as the characters. They are no longer strange but familiar, part of our linguistic stock in trade.

In poems, sounds gather meaning through suggestion. (This is why rhyme is important.) “Wabe” sounds like “wave,” and “Callooh! Callay!” isn’t far from “Hip-Hip, Hooray!” Some of the words are original portmanteau coinages. “Frabjous” combines “joyous” and a hint of “fabulous.” “Mimsy,” according to Humpty, is “flimsy” and “miserable.” No wonder everyone loves “Jabberwocky”: it turns readers into etymologists. They can make their own definitions.

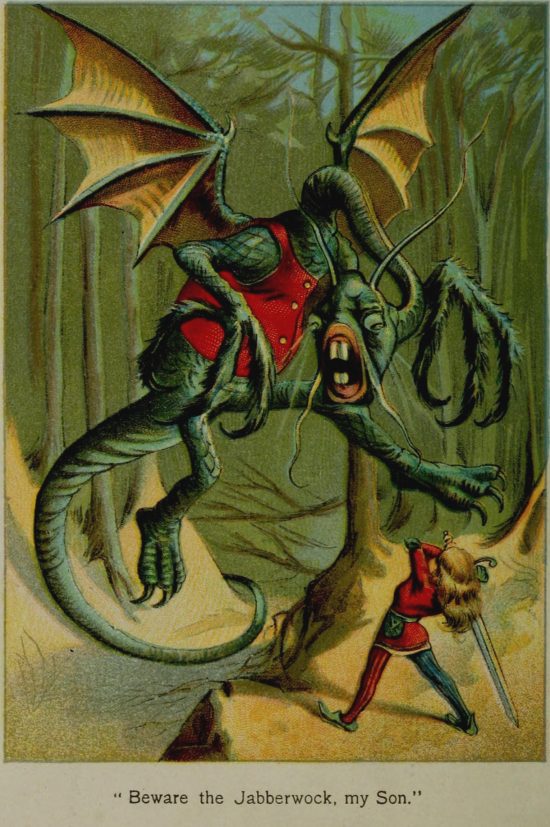

John Tenniel’s famous illustration is itself a visual portmanteau. It enhances Carroll’s vivid language—which doesn’t really describe the beast—and gives the poem a greater frisson. The Jabberwock is like one of those ancient mythical creatures composed of heterogeneous parts. His neck is a dragon’s; he has rabbit teeth and bat wings. Oh, and he’s wearing a waistcoat.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)