From The Wall Street Journal:

Fans of the Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) can take comfort in his inexhaustibility. My case is probably typical. I began reading him in my 20s, some 40 years ago, and have turned to him regularly, if in spurts, ever since. In a recent tallying-up I discovered I’d read 18 of his novels, or roughly one every two years. But there are 47 novels in all, leaving me with nearly 30 to go—some 60 years of Trollope to unfold. I find the image heartening: myself as an advanced centenarian, still with a few unread novels before me.

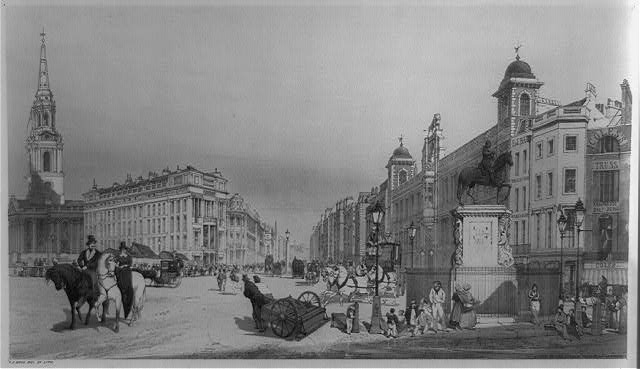

Trollope occupies a peculiar—a distorted—place in the American imagination. Fate has conspired, with the able assistance of the BBC, to portray him as a creator of landscapes so English that, under his spell, the rest of the planet falls under a distant haze. Trollope once remarked, “Visitors to England who have not sojourned at a country-house, whether it be the squire’s, parson’s, or farmer’s, have not seen the most English phase of the country.” Those country houses loom large in the BBC’s fetching Trollope adaptations, emerging in the 1970s with the vast 26-episode “The Pallisers,” continuing in the ’80s with the seven-episode “Barchester Chronicles” and extending into our century with “He Knew He Was Right” and “The Way We Live Now.”

Readers who first meet Trollope via television may be surprised to discover that in his time he was a footloose cosmopolite. Most of his early wanderings were business travel. Trollope worked for 33 years as a civil servant in the British post-office system, 20 of these years in Ireland, where the ghost of his disastrous childhood (“I was ill-dressed and dirty” and “despised by all my companions”) was successfully laid to rest. (“But from the day on which I set my foot in Ireland all these evils went away from me.”) He was later dispatched on post-office business to Egypt and Malta and Cuba. Still later, as a full-time author, he kept journeying abroad and wound up claiming five different continents as backdrops for his books: Europe, North America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It would be hard to name another 19th-century European novelist whose work was so far-flung.

Trollope’s six Palliser novels are often regarded as the crowning summit of his ranging, mountainous output. They make up a loosely bound set. Conceived singly rather than collectively, they were published over 16 years, in the midst of other projects. What chiefly unifies them are their overlapping characters and their ongoing, clamorous obsession with parliamentary politics, especially the seesawing battle between Conservatives and Trollope’s own beloved Liberals. Pursuing a lifelong dream (“to sit in the British Parliament should be the highest object of ambition to every educated Englishman”), Trollope once stood unsuccessfully for the House of Commons, and the Palliser sextet might be viewed as a benevolent revenge upon an unobliging electorate.

The final—and to my eyes the finest—volume in the series, “The Duke’s Children,” has a curious publication history. In 1878, when he submitted the novel, Trollope was in a slough, commercially and critically, and his publisher convinced him to excise 65,000 words from the outsized manuscript. For more than a century, this was the “Duke’s Children” known to the world. But in 2015, on the occasion of Trollope’s bicentennial, the Folio Society published a deluxe limited edition of the restored text in England, and Everyman offered a hardcover in the States. The book, edited by the American scholar Steven Amarnick, now appears in paperback, as an Oxford World’s Classic (678 pages, $16.95). At long last, all the children of “The Duke’s Children” are fully born.

The duke of the title is Plantagenet Palliser, probably the most memorable and certainly the noblest of Trollope’s creations. When we meet Plantagenet, in “Can You Forgive Her?,” he’s a commoner, but life has soaring grandeurs in store for him. With the death of a titled uncle, Plantagenet becomes the Duke of Omnium. And as a shyly reluctant but ever-dutiful politician, his rise is meteoric: initially, Chancellor of the Exchequer; eventually, Prime Minister.

In addition to unrivaled power (“the leading man in the greatest kingdom in the world”), Plantagenet represents something else no less notable: the near-mystical blending of traits that constitute the ideal “English gentleman.” For Trollope, as for his contemporary Gerard Manley Hopkins, the concept subsumed the personal within the national. As Hopkins put it: “If the English race had done nothing else, yet if they left the world the notion of a gentleman, they would have done a great service to mankind.” Trollope in his posthumous autobiography observed, “I think that Plantagenet Palliser, Duke of Omnium, is a perfect gentleman.” He added, acknowledging the daunting ambition of his task, “If he be not, then I am unable to describe a gentleman.”

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)