From The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works:

In early spring 2019, I started treatment on a Victorian-era publisher’s case binding bound in bright green bookcloth, never anticipating that this mass-produced binding would set into motion an engrossing exploration of a hidden hazard in library collections.

Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste (1857) had been requested for exhibit in the Winterthur galleries, and while working under the microscope to remove a waxy accretion, I was surprised to see the bright green colorant flake readily from the bookcloth with even the gentlest touch of my porcupine quill. I began to wonder whether this bright green hue came from a pigment rather than a dye, and if that might account for the lack of cohesion in the bookcloth’s colored starch coating. Aware of recent literature about Victorian wallpapers, apparel, and other household goods colored with toxic emerald green pigment, a dubious concern grew in my mind: could this same toxic pigment have been used to color nineteenth-century bookcloth?

In Winterthur’s Scientific Research and Analysis Lab, Dr. Rosie Grayburn conducted X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) on Rustic Adornments and identified the strong presence of arsenic and copper in the bookcloth. She followed the elemental analysis with Raman spectroscopy, confirming the compound copper acetoarsenite, or emerald green pigment. This revelation halted my treatment efforts and spurred us to create the Poison Book Project, an investigation of potentially toxic pigments used to color Victorian-era bookcloth. Working with library staff and conservation interns, we analyzed over 400 cloth-case publisher’s bindings in both the circulating and rare book collections at Winterthur Library. After an initial test batch in a range of colors, we decided to focus exclusively on green bookcloth for the initial phase of the project. We identified nine books bound in arsenical emerald green cloth, four of which had been housed in the circulating collection. We found a tenth emerald green binding on the shelf of a local used book store (and purchased it for $15). After scanning the Winterthur Library collection for emerald green, we reached out to The Library Company of Philadelphia. Their unique shelving practice of arranging the Americana collection chronologically allowed us to complete in a single day what had taken months to accomplish at Winterthur Library. Using Winterthur’s hand-held XRF device, we found 28 volumes among The Library Company’s nineteenth-century American and British publisher’s bindings that tested positive for arsenic. We will be expanding our data set even further in cooperation with the University of Delaware Library Special Collections.

Once we knew emerald green book cloth is not uncommon, we needed to understand what sort of risk it actually poses for library staff, researchers, and book collectors. We reached out to the University of Delaware Soil Testing Lab for quantitative analysis of a destructive sample of bookcloth. The results were higher than any of us had anticipated. A toxic dose of emerald green, when ingested or inhaled, can be as low as 5 mg/kg of body weight, and much lower, chronic doses have been linked to non-lethal health complications. The amount of emerald green colorant in the tested bookcloth averaged 2.5 mg/cm2. Pick-up tests conducted by rolling a dry cotton swab across the surface of the bookcloth also showed a significant degree of arsenic in the pigment offset. These tests were performed on a single binding, so further research is needed to understand whether all or most emerald green bookcloth exhibits this level of friability.

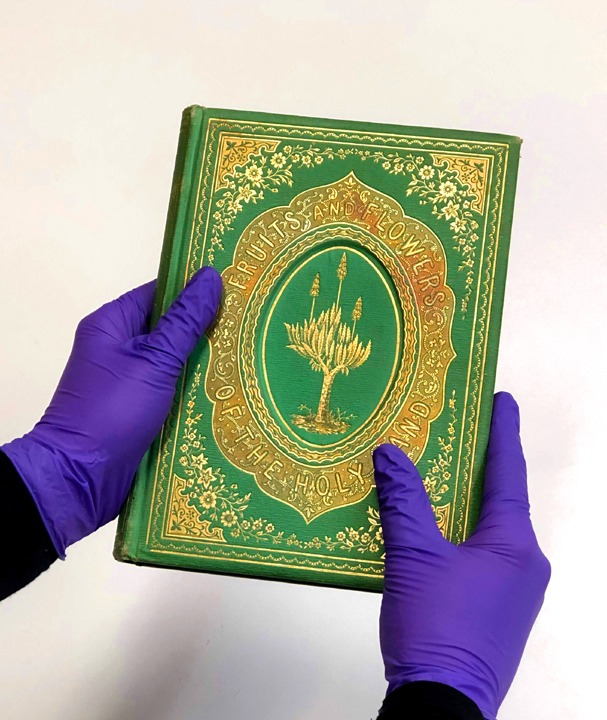

The director of environmental health and safety at the University of Delaware, Michael Gladle, provided us with context from an industrial hygiene perspective. Without a U.S. safety standard for arsenic exposure, as there is for lead, he cautioned us to consider any direct exposure unacceptable. Based on his recommendations, Winterthur Library will encourage patrons to turn first to digitized versions of books bound in emerald green cloth. However, given the nature of our researchers, who are attracted to our collections in American material culture primarily in their tangible form, we are also working to develop a safe handling protocol and training procedure. This conversation must involve multiple stakeholders including library staff, conservation staff, division leaders, industrial hygiene consultants, and legal counsel. For staff who must handle these books, wearing nitrile gloves followed by hand-washing is our current best practice. Winterthur Library has relocated all emerald green books into the rare book collection, where they will be stored in a single location. Storing the books together will make cautionary labeling easier and more effective and will also facilitate safer salvage response in case of a collections emergency. Emerald green books are individually sealed in zip-top, polyethylene baggies to isolate the friable pigment and to prevent offset from the bookcloth rubbing against neighboring books on the shelf. For conservators who must treat a book bound in emerald green bookcloth, Michael Gladle strongly recommends wearing nitrile gloves and working under a certified chemical fume hood, because the use of liquid adhesives or heat can increase the risk of arsenic exposure.

. . . .

Currently, project interns are working on scanning the Winterthur Library collections for chromium-based pigments, which are significantly less toxic than arsenic but are still cause for concern when found in library collections. Next steps for the project will involve scanning for additional pigments; deeper archival research into the manufacture of nineteenth-century English bookcloth; partnering with other institutions to expand our data set of arsenical bindings; and creating a publicly-accessible, searchable database of bindings which have been analyzed at Winterthur and other institutions.

Link to the rest at The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works

I watched a historical documentary a few months about the Victorian house (Absolute History was the YT channel I believe) and this particular color/paper was widely used for wallpaper and the like in hundreds of thousands of homes during that time period. This stuff was used for decades and it was a fantastic way for a house to slowly kill their occupants.

So according to this story 5 mg per kg of my body weight is considered toxic, and the book binding when destroyed tested out at a whole 2.5mg per square cm. So if i were to weigh 200 pounds, I would need to eat 450 square cms of the book binding!

I think being exposed to radiation from bananas, grass, sunlight, and all other natural/organic radiation sources is probably a more relevant concern for me even if i worked in a historical library. I probably have a better chance of dying from blood loss from papercuts vs this toxic poisoning. But in case any of you are worried, my recommendation isn’t to wear gloves while handling the books. Maybe just decide to only eat a PORTION of the cover at one meal. Moderation is really the key for any good diet program.

given the nature of our researchers, who are attracted to our collections in American material culture primarily in their tangible form

(ie, they are luddites, and nothing can be done)