From Writer Unboxed:

I suspect we all know people who will walk in a room and say something like, “I still can’t believe she’d quit on me.” I’m married to one of them.

It’s obvious there is conflict, so this might end up being a good story, but right now the comment is floating in space. I’ll need more words to understand it. Who is this woman? Where did he see her? When did this happen—ten minutes ago? Is he still chewing on something from his youth? Or is this a future action that worries him?

One thing is for sure: to assume that I can read his mind is a sweet yet preposterous overestimate of my editorial prowess. I suppose that’s what happens after you’ve been married a few decades.

But judging from the manuscripts I see, it can also be what happens when you are on your umpteenth draft of a novel and can no longer remember which version of which facts are on the page. For that reason, it can be helpful if at some point, before sending your manuscript to beta readers or developmental editors, you take one pass to make sure that you’ve set each scene appropriately.

Although reportage is different than story-building (for more on this you can check my previous post on paragraphing), borrowing the journalist’s 5 W’s can inspire a set of useful questions that will ensure that the scene you’re building is also giving the reader the information she needs.

Who took action, and who did it affect?

What happened, exactly?

Where did it take place?

When did it take place?

Why did it happen, and why does it matter to this particular story and this particular protagonist?

Wait—didn’t you say 3 W’s?

The bare minimum we need at the outset of a scene is the who, when, and where. With that information, “I still can’t believe she’d quit on me” gains context:

It’s been ten years and Simone’s clothes still hang in the back of my closet. I still can’t believe she quit on me.

~or~

I still can’t believe what just happened at the office—Joanna up and walked out on our partnership.

~or~

I backslid at Ed’s retirement lunch; I couldn’t resist the shrimp scampi. I still can’t believe Cleo warned me to stop eating garlic or she’d quit training me at the gym.

I was thinking about this topic after a question was posed on a Facebook page about how to cleverly fold in these details without being as pedestrian as, say, “Meanwhile, back at the ranch, his brother…” The thing is, though, those seven “pedestrian” words perfectly orient us to who, when, and where.

When it comes to setting your scene, clarity—not cleverness—should be your first priority. Let’s look at how that’s done.

Examples from a Master

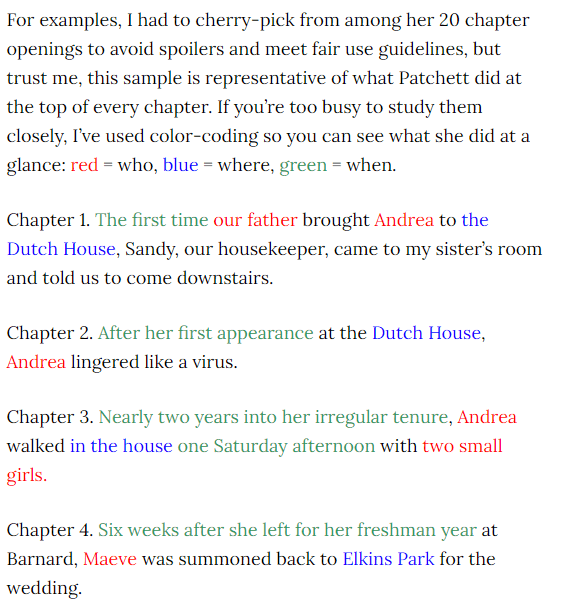

As it happened, on the day that question was posted, I had just finished reading The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. It’s the story of two siblings who cannot overcome a past symbolized by the grandiose home that their father had bought—fully furnished by its previous Dutch occupants—for their unappreciative mother, who then left the family. Patchett is an author at the top of her game, and she had plenty of game to start with. Among this bestselling title’s many accolades, it was a 2020 Pulitzer Prize finalist.

. . . .

Link to the rest at Writer Unboxed

“I still can’t believe she’d quit on me”

Or “That damn Harley died right there on Dead Man’s Curve.”