From Writer Unboxed:

My publisher engaged a sensitivity reader to evaluate the portrayal of a neurodiverse character in my summer 2023 release (The Beauty of Rain). I eagerly anticipated the reader’s feedback, whose notes on that aspect of the manuscript were ultimately helpful and unsurprising. Conversely, her recommendation that I add trigger warnings about suicidal ideation and prescription drug abuse did momentarily throw me.

Most everyone knows that a trigger warning is essentially a statement cautioning a consumer/reader that the content may be disturbing or induce a traumatic response. Although these labels are not as commonplace in publishing as they are in film, television, and music, in recent years they’ve begun to appear on a book’s digital detail page, its back jacket, or in an author’s note. The big argument in favor of such labels is that they give a reader the choice to avoid a book that contains material said reader might find harmful or that could unwittingly force them to revisit past trauma.

While I consider myself to be a compassionate person who would never purposely cause someone harm, my initial reaction was to reject the suggestion. Trust me, I know that sounds awful, but I worried that the warnings somewhat mischaracterized the tone and themes in my work. After all, if A Man Called Ove had included a suicidal ideation warning, many people might have missed out on an extremely life-affirming story. I discussed my concern with my agent and editor, both of whom also expressed doubts about the necessity of the warnings.

Coincidentally, around that same time I was doom-scrolling on Twitter and came across a New Yorker article from 2021 entitled “What if trigger warnings don’t work?” That piece discusses studies conducted with respect to the effectiveness of content warnings in academia (which are on the rise). The data suggests that such warnings not only don’t work, but they may inflict more harm by causing additional stress and reinforcing the idea that a trauma is central to a survivor’s identity (which is the opposite of PTSD therapy goals). On Twitter and in an Authors Guild discussion thread on this topic, more than one licensed therapist concurred with the article’s conclusions and believed trigger warnings had no meaningful effect.

You might think this data cemented my decision, but it merely piqued my interest in the topic. What better excuse to procrastinate writing my next book than to dive down the rabbit hole of articles and blog posts about the pros and cons of trigger warnings in literature?

It did not take long to identify some other commonly debated pitfalls, which include:

- Spoilers: One simplistic and popular complaint is that a content warning may give away a plot twist and thus spoil the story for every reader, which is especially frustrating for those who didn’t want the warning. This camp argues that, prior to purchase, a sensitive reader can visit websites such as Book Trigger Warnings or Trigger Warning Database to verify whether a particular book contains personally troubling content without forcing the author to ruin the surprise or twist for every potential reader who picks up the book.

- Trigger Identification: There are as many different triggers as there are readers, making it a practical impossibility to adequately warn every potential reader about every potential trigger. Similarly, readers with comparable experiences might have different reactions and preferences (for example, I was raised in a violent home but did not want or need a warning before reading The Great Alone). We can certainly group some content into broad common categories like domestic abuse, addiction, rape, etc., but what about a reader who might be traumatized by something more obscure (like a color or a setting)? It seems ambitious if not impossible to imagine one could create a list of all possible triggers. If we can’t screen every scenario, is it fair to screen any?

- Genre expectations: In dark romance, for example, it is almost guaranteed that there will be some level of violence and crime (such as kidnapping the heroine or dubious consent). The same could be said of crime novels and thrillers (graphic violence, rape, murder, mental health matters). Should authors and publishers need to take additional steps to prepare a reader for something that is essentially foundational to that genre?

- Censorship: Some teachers, librarians, and publishing professionals argue that content labels are a form of censorship, and that the line between labels and trigger warnings is thin. They worry an overreach or abuse of these labels could result in many books being segregated onto separate shelves. For example, YA books often tackle an array of topics from fatphobia to date rape. If the use of multiple warnings persists and leads to segregated shelving, those books might become less visible and accessible to the general public who might otherwise benefit from exploring those topics. This slippery slope could also ultimately affect what stories publishers choose to invest in and distribute, which would be bad for both authors and readers.

In my opinion, some of these arguments hold more weight than others. I haven’t had an epiphany when it comes to their efficacy, nor am I convinced that there is a clear right answer to this complicated question. That said, my research journey helped me focus on the decision I had to make and its effect on my writing goals. I write stories because I want to emotionally connect with others. Would I prefer to have as many readers as possible give my story a chance? Yes. But do I want to sell my books to everyone at any cost, including the potential emotional torment of another? No, of course not.

Link to the rest at Writer Unboxed

PG wonders how humankind was able to evolve from pond scum into its present form without trigger warnings.

Somehow, the ancient Egyptians managed to build an amazing civilization without trigger warnings. (PG doesn’t read hieroglyphics, so he can’t be certain, but he doesn’t think he’s ever seen a hieroglyphic that looked like it might be a trigger warning.)

The Greeks and Romans built amazing civilizations without trigger warnings. He’s not aware of any Latin text that translates to: “This scroll contains references to alcohol consumption, violence using fantasy magic, and panic attacks.”

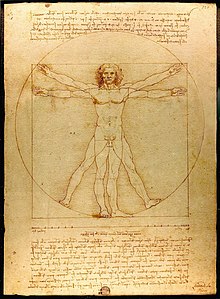

Nor did the great artists and writers of the Renaissance ever include trigger warnings.

Pieter Bruegel didn’t have trigger warnings for any of his paintings.

Nor did Leonardo da Vinci.

Nor did Stephen Crane:

At times he regarded the wounded soldiers in an envious way. He conceived persons with torn bodies to be peculiarly happy. He wished that he, too, had a wound, a red badge of courage.

Nor did Siegfried Sassoon:

Do you remember the dark months you held the sector at Mametz

The nights you watched and wired and dug and piled sandbags on parapets?

Do you remember the rats; and the stench

Of corpses rotting in front of the front-line trench–

And dawn coming, dirty-white, and chill with a hopeless rain?

Do you ever stop and ask, ‘Is it all going to happen again?’Do you remember that hour of din before the attack–

And the anger, the blind compassion that seized and shook you then

As you peered at the doomed and haggard faces of your men?

Do you remember the stretcher-cases lurching back

With dying eyes and lolling heads–those ashen-grey

Masks of the lads who once were keen and kind and gay?

“The following book contains depictions of mature adults behaving like real humans, making mistakes, behaving badly, and dealing with the consequences of their own actions. Not for the faint of heart.”

This seems to be an issue with indie writers on Amazon. I’ve heard of a few who said their books were taken down because readers complained about the violence in their stories. The writers had to include trigger warnings to get their books back up.

It’s possible this is limited to a specific genre, specifically the “dark romance” or gothic genres, which I think those authors write in. I’ve never heard of mystery or horror authors having this problem. Then again, what case could one make for being traumatized if one willingly reads “Silence of the Lambs” or a book with a monster on the cover? You don’t read books about cannibals if you have an aversion to gore. I do have such an aversion, so I’ve never read “Silence of the Lambs.”

Although, if I remember correctly, back in the day a variant of trigger warnings was used as a selling hook. I think the Twilight Zone or Outer Limits used to suggest the viewer will be shocked or bemused by what they’re about to see. Books with narrators, or told in first person used to suggest in the first pages that the story they’re about to tell is going to haunt you in some fashion. But readers considered those “warnings” to be promises that a good story awaited them.

An alternative headline might be, “To Read Or Not To Read.”

If one is so sensitive that reading may trigger serious consequences, then don’t read.

I love the poetry of Seigfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

As for trigger warnings, there will always live among us two kinds of people. Those who, if they don’t personally like something, will simply put it down or turn it off or not attend, and those who, if they don’t personally like something, will attempt to ban it for everybody, thereby cementing their status as the perfect portrayal of the south end of any mammal who is naked, bent forward at the waist, and headed north.