From Writer Unboxed:

After the excitement of a “yes” from a publisher comes the job of assessing your publishing contract.

Facing down ten pages of dense legalese can be a daunting task, especially for new and inexperienced writers, who may not have the resources to hire a literary lawyer, or have access to a knowledgeable person who can help de-mystify the offer terms.

And it is really, really important to assess and understand those terms, because publishing contracts are written to the advantage of publishers. While a good contract should strike a reasonable balance between the publisher’s interests and the writer’s benefit, a bad contract…not so much.

. . . .

After the excitement of a “yes” from a publisher comes the job of assessing your publishing contract.

Facing down ten pages of dense legalese can be a daunting task, especially for new and inexperienced writers, who may not have the resources to hire a literary lawyer, or have access to a knowledgeable person who can help de-mystify the offer terms.

And it is really, really important to assess and understand those terms, because publishing contracts are written to the advantage of publishers. While a good contract should strike a reasonable balance between the publisher’s interests and the writer’s benefit, a bad contract…not so much.

In this article, I’m going to focus on contract language that gives too much benefit to the publisher, and too little to the author. Consider these contract clauses to be red flags wherever you encounter them. (All of the images below are taken from contracts that have been shared with me by authors.)

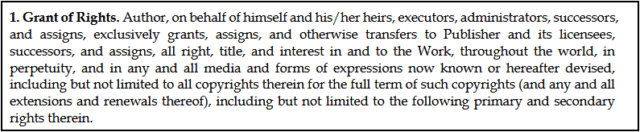

Copyright Transfer

Unless you are doing work-for-hire, such as writing for a media tie-in franchise, a publisher should not take ownership of your copyright. For most publishers, copyright ownership doesn’t provide any meaningful advantage over a conventional grant of rights, and there’s no reason to require it. Even where the transfer is temporary, with rights reverting back to you at some point, it doesn’t change the fact that for as long as the contract is in force, your copyright does not belong to you.

Copyright transfers usually appear in the Grant of Rights clause. Look for phrases like “all right, title and interest in and to the Work” and “including but not limited to all copyrights therein.”

Watch out also for contracts where a copyright transfer in the Grant of Rights clause is contradicted by language later on–such as requiring the publisher to print a copyright notice in the name of the author (which shouldn’t be possible if the author no longer owns the copyright). For one thing, you don’t want your contract to be internally contradictory, which could pose legal issues down the road. For another, such contradictions suggest that the publisher doesn’t understand its own contract language, which is never a good thing.

There’s more on the not-uncommon problem of internal contradictions here.

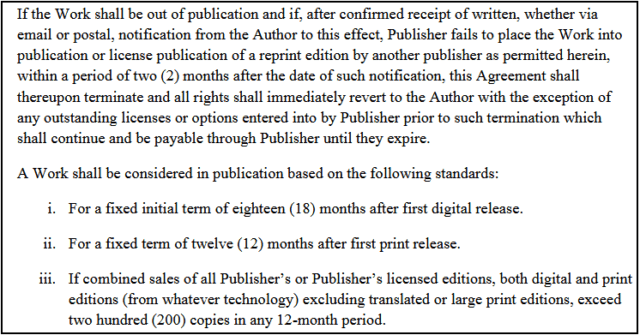

Life of Copyright Grant Without Adequate Reversion Language

Big publishers routinely require you to grant rights for the full term of copyright (in the US, Canada, and most of Europe, your lifetime plus 70 years). Although they’re more likely to offer time-limited contracts, many smaller presses do as well.

Contrary to much popular belief, this is not necessarily a red flag…as long it’s balanced by clear, detailed language that ensures you can request contract termination and rights reversion once sales drop below specific benchmarks: for example, fewer than 100 copies sold during the previous 12 months, or less than $250 in royalties paid in each of two prior royalty periods. Publishers like to sit on rights, because they can make money from even low-selling books if they have a big enough catalog. Authors, on the other hand, don’t benefit from a book that’s selling only a handful of copies and getting no promotional support. At that point, it’s better to be able to revert your rights and do something else with them.

If you’re offered a contract with a life of copyright grant term, the first thing you should look at is the termination and reversion clause. A good clause will be specific about when and how the book will go “out of print” or “out of publication”, and what the author can do to terminate the contract once that happens.

In the clause below, the definition of “in publication” is tied to objective standards, including minimum sales numbers, and there’s a clear procedure for both the author and publisher to follow to request and grant rights reversion once falling sales take the book “out of publication”.

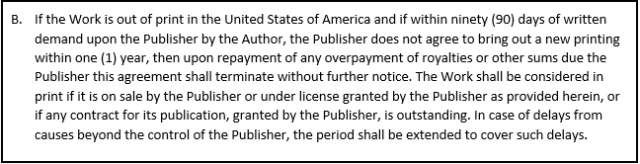

By contrast, here’s an example of a poor reversion clause.

Defining “in print” as “on sale by the Publisher” (similar problematic terminology: “available for sale in any edition” or “available for sale through the ordinary channels of the book trade”) means that an ebook edition available only on the publisher’s website would qualify as “in print”, even if it was barely selling or not selling at all. Since it costs little or nothing to keep a book “available” this way, the publisher has no incentive ever to take the book “out of print”, and the author has no leverage to compel the return of rights.

. . . .

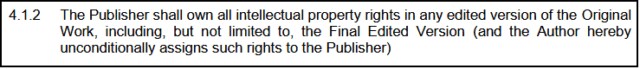

Claiming Copyright on Edits

Can a publisher claim that it owns the copyright on the editing it provides?

As far as I know there’s no legal precedent for such a claim, and the very limited legal discussion I’ve seen leans toward the view that editing process doesn’t give the publisher—or the editor—any copyright ownership. After all, other than copy editing, most editing is a collaboration between author and editor, with the bulk of the work done by the author.

Claiming copyright on edits is not standard publishing practice. Nevertheless, some publishers do attempt it, either with an outright claim of copyright on the final version of the work…

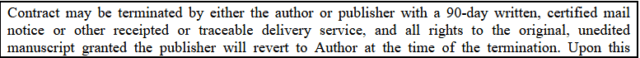

…or simply a claim on the edits themselves (telltale language: “original, unedited manuscript”):

It’s unlikely that either of these clauses would hold up in court—especially the first one: among other things, the presence of a copyright notice in the author’s name inside the book would certainly seem to indicate the publisher’s acknowledgment of the author’s ownership of the finished product. What good does it do the publisher to hoard edits on a book it doesn’t own, anyway? What difference does it make if an author re-publishes their fully-edited book once rights have reverted? Claiming copyright on edits is simply pointless and greedy.

Editing copyright claims can occur throughout a contract: I’ve seen them in the grant of rights section, the termination section, and the editing section. So keep a sharp eye out.

Net Profit Royalties

While larger publishing houses tend to pay royalties as a percentage of a book’s list price, smaller publishers often pay based on net revenue or net sales income: list price less wholesalers’ and retailers’ discounts and channel fees.

Less common are royalty payments on net profit: list price less discounts less some or all of the expense of publishing.

Net profit royalty clauses are always a contract red flag. Even at higher royalty percentages, expense deductions can drastically reduce the amount on which your royalties are based: that 50% royalty may seem generous, but depending on what’s taken out before it’s calculated, what you actually receive may turn out to be much less than you expected. Additionally, net profit royalties are a temptation for publishers manipulate expenses to make author payments as small as possible.

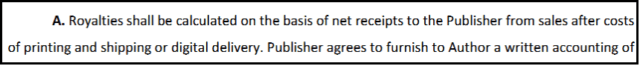

Here’s a fairly straightforward example of a net profit royalty: sales receipts less printing and shipping.

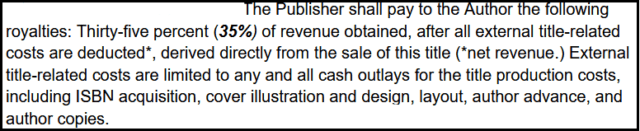

Here’s a clause that deducts much more, including ISBN, cover art, layout and formatting, author copies, and possibly other costs. Not only does this have the potential to reduce your royalty to a pittance, you won’t have any idea of why you were paid what you were paid unless the publisher provides an itemized accounting.

Some publishers with net profit royalties confuse the issue by claiming to pay on “gross income” or “net sales price” or similar terms that don’t include the word “profit”. This is why you always want to see a precise definition of whatever terminology the publisher uses to describe its royalty payments, so you can be sure exactly how your royalties will be calculated. The absence of such a definition is another red flag.

Link to the rest at Writer Unboxed

Long-time visitors will recall these and many other items from PG’s posts from a long time ago.

The bottom line is:

- Read any Publishing Contract, regardless of whether it’s from a small publisher or a very large one.

- Don’t sign a contract that contains any provisions you don’t understand.

- Don’t trust a contract that someone on the other side of the contract or your agent says is “a Standard Contract.”

Unlike many contracts that individuals are asked to sign, book publishing contracts are not regulated in any meaningful way.

If you want to get a new Visa credit card, there are lots of laws that limit what terms may be included in the credit card contract.

This is definitely Not the case with a publishing contract.

It costs much, much less to hire a literary attorney to examine the contract before you sign it than it does to hire that same attorney to get you and your book(s) out of a publishing contract after you’ve signed it.

PG knows because that those two services occupied much of his professional time before he pulled down his shingle. Examining a contract before it was signed cost hundreds of dollars. After it was signed, getting an author out of that contract cost thousands of dollars.

(No, PG is not coming our of retirement. Been there, done that, quit paying for malpractice insurance.)