From The Harvard Business Review:

The theory of disruptive innovation, introduced in these pages in 1995, has proved to be a powerful way of thinking about innovation-driven growth. Many leaders of small, entrepreneurial companies praise it as their guiding star; so do many executives at large, well-established organizations, including Intel, Southern New Hampshire University, and Salesforce.com.

Unfortunately, disruption theory is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success. Despite broad dissemination, the theory’s core concepts have been widely misunderstood and its basic tenets frequently misapplied. Furthermore, essential refinements in the theory over the past 20 years appear to have been overshadowed by the popularity of the initial formulation. As a result, the theory is sometimes criticized for shortcomings that have already been addressed.

There’s another troubling concern: In our experience, too many people who speak of “disruption” have not read a serious book or article on the subject. Too frequently, they use the term loosely to invoke the concept of innovation in support of whatever it is they wish to do. Many researchers, writers, and consultants use “disruptive innovation” to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and previously successful incumbents stumble. But that’s much too broad a usage.

The problem with conflating a disruptive innovation with any breakthrough that changes an industry’s competitive patterns is that different types of innovation require different strategic approaches. To put it another way, the lessons we’ve learned about succeeding as a disruptive innovator (or defending against a disruptive challenger) will not apply to every company in a shifting market. If we get sloppy with our labels or fail to integrate insights from subsequent research and experience into the original theory, then managers may end up using the wrong tools for their context, reducing their chances of success. Over time, the theory’s usefulness will be undermined.

This article is part of an effort to capture the state of the art. We begin by exploring the basic tenets of disruptive innovation and examining whether they apply to Uber. Then we point out some common pitfalls in the theory’s application, how these arise, and why correctly using the theory matters. We go on to trace major turning points in the evolution of our thinking and make the case that what we have learned allows us to more accurately predict which businesses will grow.

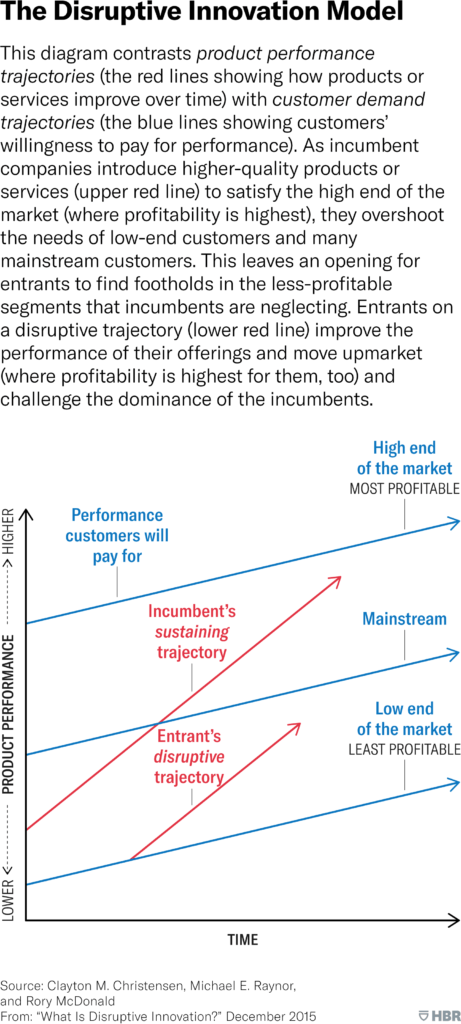

First, a quick recap of the idea: “Disruption” describes a process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others. Entrants that prove disruptive begin by successfully targeting those overlooked segments, gaining a foothold by delivering more-suitable functionality—frequently at a lower price. Incumbents, chasing higher profitability in more-demanding segments, tend not to respond vigorously. Entrants then move upmarket, delivering the performance that incumbents’ mainstream customers require, while preserving the advantages that drove their early success. When mainstream customers start adopting the entrants’ offerings in volume, disruption has occurred. (See the exhibit “The Disruptive Innovation Model.”)

Is Uber a Disruptive Innovation?

Let’s consider Uber, the much-feted transportation company whose mobile application connects consumers who need rides with drivers who are willing to provide them. Founded in 2009, the company has enjoyed fantastic growth (it operates in hundreds of cities in 60 countries and is still expanding). It has reported tremendous financial success (the most recent funding round implies an enterprise value in the vicinity of $50 billion). And it has spawned a slew of imitators (other start-ups are trying to emulate its “market-making” business model). Uber is clearly transforming the taxi business in the United States. But is it disrupting the taxi business?

According to the theory, the answer is no. Uber’s financial and strategic achievements do not qualify the company as genuinely disruptive—although the company is almost always described that way. Here are two reasons why the label doesn’t fit.

Disruptive innovations originate in low-end or new-market footholds.

Disruptive innovations are made possible because they get started in two types of markets that incumbents overlook. Low-end footholds exist because incumbents typically try to provide their most profitable and demanding customers with ever-improving products and services, and they pay less attention to less-demanding customers. In fact, incumbents’ offerings often overshoot the performance requirements of the latter. This opens the door to a disrupter focused (at first) on providing those low-end customers with a “good enough” product.

In the case of new-market footholds, disrupters create a market where none existed. Put simply, they find a way to turn nonconsumers into consumers. For example, in the early days of photocopying technology, Xerox targeted large corporations and charged high prices in order to provide the performance that those customers required. School librarians, bowling-league operators, and other small customers, priced out of the market, made do with carbon paper or mimeograph machines. Then in the late 1970s, new challengers introduced personal copiers, offering an affordable solution to individuals and small organizations—and a new market was created. From this relatively modest beginning, personal photocopier makers gradually built a major position in the mainstream photocopier market that Xerox valued.

A disruptive innovation, by definition, starts from one of those two footholds. But Uber did not originate in either one. It is difficult to claim that the company found a low-end opportunity: That would have meant taxi service providers had overshot the needs of a material number of customers by making cabs too plentiful, too easy to use, and too clean. Neither did Uber primarily target nonconsumers—people who found the existing alternatives so expensive or inconvenient that they took public transit or drove themselves instead: Uber was launched in San Francisco (a well-served taxi market), and Uber’s customers were generally people already in the habit of hiring rides.

Uber has quite arguably been increasing total demand—that’s what happens when you develop a better, less-expensive solution to a widespread customer need. But disrupters start by appealing to low-end or unserved consumers and then migrate to the mainstream market. Uber has gone in exactly the opposite direction: building a position in the mainstream market first and subsequently appealing to historically overlooked segments.

Disruptive innovations don’t catch on with mainstream customers until quality catches up to their standards.

Disruption theory differentiates disruptive innovations from what are called “sustaining innovations.” The latter make good products better in the eyes of an incumbent’s existing customers: the fifth blade in a razor, the clearer TV picture, better mobile phone reception. These improvements can be incremental advances or major breakthroughs, but they all enable firms to sell more products to their most profitable customers.

Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, are initially considered inferior by most of an incumbent’s customers. Typically, customers are not willing to switch to the new offering merely because it is less expensive. Instead, they wait until its quality rises enough to satisfy them. Once that’s happened, they adopt the new product and happily accept its lower price. (This is how disruption drives prices down in a market.)

Most of the elements of Uber’s strategy seem to be sustaining innovations. Uber’s service has rarely been described as inferior to existing taxis; in fact, many would say it is better. Booking a ride requires just a few taps on a smartphone; payment is cashless and convenient; and passengers can rate their rides afterward, which helps ensure high standards. Furthermore, Uber delivers service reliably and punctually, and its pricing is usually competitive with (or lower than) that of established taxi services. And as is typical when incumbents face threats from sustaining innovations, many of the taxi companies are motivated to respond. They are deploying competitive technologies, such as hailing apps, and contesting the legality of some of Uber’s services.

Why Getting It Right Matters

Readers may still be wondering, Why does it matter what words we use to describe Uber? The company has certainly thrown the taxi industry into disarray: Isn’t that “disruptive” enough? No. Applying the theory correctly is essential to realizing its benefits. For example, small competitors that nibble away at the periphery of your business very likely should be ignored—unless they are on a disruptive trajectory, in which case they are a potentially mortal threat. And both of these challenges are fundamentally different from efforts by competitors to woo your bread-and-butter customers.

As the example of Uber shows, identifying true disruptive innovation is tricky. Yet even executives with a good understanding of disruption theory tend to forget some of its subtler aspects when making strategic decisions. We’ve observed four important points that get overlooked or misunderstood:

1. Disruption is a process.

The term “disruptive innovation” is misleading when it is used to refer to a product or service at one fixed point, rather than to the evolution of that product or service over time. The first minicomputers were disruptive not merely because they were low-end upstarts when they appeared on the scene, nor because they were later heralded as superior to mainframes in many markets; they were disruptive by virtue of the path they followed from the fringe to the mainstream.

Because disruption can take time, incumbents frequently overlook disrupters.

Most every innovation—disruptive or not—begins life as a small-scale experiment. Disrupters tend to focus on getting the business model, rather than merely the product, just right. When they succeed, their movement from the fringe (the low end of the market or a new market) to the mainstream erodes first the incumbents’ market share and then their profitability. This process can take time, and incumbents can get quite creative in the defense of their established franchises. For example, more than 50 years after the first discount department store was opened, mainstream retail companies still operate their traditional department-store formats. Complete substitution, if it comes at all, may take decades, because the incremental profit from staying with the old model for one more year trumps proposals to write off the assets in one stroke.

The fact that disruption can take time helps to explain why incumbents frequently overlook disrupters. For example, when Netflix launched, in 1997, its initial service wasn’t appealing to most of Blockbuster’s customers, who rented movies (typically new releases) on impulse. Netflix had an exclusively online interface and a large inventory of movies, but delivery through the U.S. mail meant selections took several days to arrive. The service appealed to only a few customer groups—movie buffs who didn’t care about new releases, early adopters of DVD players, and online shoppers. If Netflix had not eventually begun to serve a broader segment of the market, Blockbuster’s decision to ignore this competitor would not have been a strategic blunder: The two companies filled very different needs for their (different) customers.

However, as new technologies allowed Netflix to shift to streaming video over the internet, the company did eventually become appealing to Blockbuster’s core customers, offering a wider selection of content with an all-you-can-watch, on-demand, low-price, high-quality, highly convenient approach. And it got there via a classically disruptive path. If Netflix (like Uber) had begun by launching a service targeted at a larger competitor’s core market, Blockbuster’s response would very likely have been a vigorous and perhaps successful counterattack. But failing to respond effectively to the trajectory that Netflix was on led Blockbuster to collapse.

2. Disrupters often build business models that are very different from those of incumbents.

Consider the healthcare industry. General practitioners operating out of their offices often rely on their years of experience and on test results to interpret patients’ symptoms, make diagnoses, and prescribe treatment. We call this a “solution shop” business model. In contrast, a number of convenient care clinics are taking a disruptive path by using what we call a “process” business model: They follow standardized protocols to diagnose and treat a small but increasing number of disorders.

One high-profile example of using an innovative business model to effect a disruption is Apple’s iPhone. The product that Apple debuted in 2007 was a sustaining innovation in the smartphone market: It targeted the same customers coveted by incumbents, and its initial success is likely explained by product superiority. The iPhone’s subsequent growth is better explained by disruption—not of other smartphones but of the laptop as the primary access point to the internet. This was achieved not merely through product improvements but also through the introduction of a new business model. By building a facilitated network connecting application developers with phone users, Apple changed the game. The iPhone created a new market for internet access and eventually was able to challenge laptops as mainstream users’ device of choice for going online.

Link to the rest at The Harvard Business Review

PG realized he has been throwing around disruptive innovation and related terms for quite a while, assuming (like a tech-head) that everyone understood the concept in the same way he did.

While PG doesn’t necessarily accept all of the factors the HBR describes as necessary to qualify as disruptive, he thinks the article will help educate visitors to TPV who have better things to do than to follow this and that business trend.