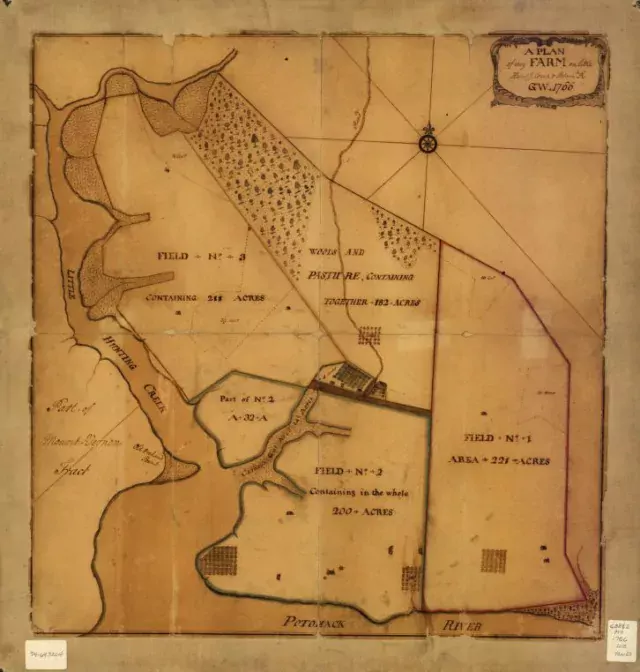

A plan of my farm on Little Huntg. Creek & Potomk. R., George Washington (Library of Congress)

From The Wall Street Journal:

On July 1, 1776, as the Declaration of Independence was about to be published, its author complained to a friend that it was painful, at such a fraught moment, to be in Philadelphia, “300 miles from one’s country.”

Thomas Jefferson’s sentiment, expressed casually in a private letter, reveals an arresting fact—namely, that the new nation did not yet exist even in the mind of the man who announced its birth. This inchoate quality was obvious in the sense that the 13 former colonies, united only in their bid for independence, didn’t create a genuine national government for more than a decade. But Jefferson’s remark hit on something more elemental, the geopolitical space that a citizen intuitively recognizes as “one’s country.”

Michael Barone’s “Mental Maps of the Founders” focuses on this spatial sense among key members of the revolutionary generation. By “mental maps,” Mr. Barone intends more than a regional affinity. He means a “geographical orientation”—the perspective that place confers. He argues that, for the Founders, it shaped “what the new nation they hoped they were creating would look like and be like.”

Mr. Barone, a distinguished journalist and political analyst, develops his theme through a series of six biographical portraits. He argues, for example, that the crucial event in George Washington’s life was his military campaign to oust the French from the Ohio country in 1754. A skirmish during that adventure began the Seven Years’ War, a struggle for empire waged across Europe, the Americas and Asia. Though Horace Walpole, writing in his diary in London, didn’t know Washington by name, he was referring to him when he wrote that “a volley fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America set the world on fire.” Washington’s youthful involvement in winning the Northwest established, for him, a lifelong sense of its strategic importance for any predominate power in North America. Almost by reflex, Mr. Barone writes, Washington “looked west by northwest from the front door of his beloved Mount Vernon to the continental nation he did more than anyone else to establish.”

The original 13 states could be easily divided into distinctive regional cultures: Puritan New England, with its homogeneous population and communal religious foundations; the pluralistic middle states, established by Quakers, the Dutch and Catholics, pragmatically preoccupied with commerce rather than political abstractions; and the Deep South, set apart by its planter elite and an overwhelming dependence on slave labor. Virginia, the largest state and the home of three of the Founders in Mr. Barone’s survey—Jefferson, Washington and James Madison—didn’t wholly belong to any of these regional blocks but possessed elements of each.

The other three figures in Mr. Barone’s study—Benjamin Franklin, Albert Gallatin and Alexander Hamilton—were immigrants to the regions in which they settled. Hamilton was born in the West Indies and settled in New York. Today we recognize his origins as the background of an immigrant. But Franklin also left one British colony (Massachusetts) and settled in another (Pennsylvania). And both men were born British subjects. Not so Gallatin, the Treasury secretary under both Jefferson and Madison, who came to America from the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Mr. Barone argues that these figures’ experiences as successful outsiders within their communities gave them a broader national outlook than that of their more insular countrymen.

The Founders’ geographical visions, as Mr. Barone shows, informed their sense of how America’s distinctive regional cultures might fuse into a common whole. Hamilton, inspired by the trade and credit networks that made the small sugar islands of his birth into engines of imperial wealth, favored a strong central government backed by a fiscal system that earned the loyalty of elites in all sections. Jefferson, dreaming of an egalitarian republic from his elevated place in Virginia’s planter aristocracy, believed in the proliferation of independent yeoman farmers united by an instinctive love of liberty. Madison, characteristically, added a more realistic version of Jefferson’s slightly utopian ideas. Pluralistic expansion, he felt, would prevent any one region from dominating the rest. The problem was not, in his view, too many regional subcultures but too few. These philosophical differences are well known, but Mr. Barone persuasively describes the place-derived assumptions underlying them.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal