From The Wall Street Journal:

In the November 1923 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, Lucy Truman Aldrich published an account of an unusual experience she had in China earlier in the year. “For the rest of my life,” Aldrich began her tale, “when I am ‘stalled’ conversationally, it will be a wonderful thing to fall back on: ‘Oh, I must tell you about the time I was captured by Chinese bandits.’ ”

On May 6, 1923, Aldrich, the sister-in-law of American financier John D. Rockefeller Jr., was among 300 travelers on board the Peking Express, an overnight train bound north to the capital (now Beijing). Beginning service in late 1922, the Peking Express was China’s entry into the world of luxury train travel, the equal of anything found in Europe or America. For first-class passengers like Aldrich, who departed from Shanghai, the train promised silk sheets in the sleeping compartments, silver and linen on the dining tables, and a Victorian-style drawing room.

China’s weak central government had enabled the proliferation of warlords who commanded personal armies, and travelers in the countryside frequently found themselves at the mercy of bandits and highwaymen. The Peking Express, with its steel carriages and sizable force of private security guards, offered its passengers immunity from the chaotic world outside its sturdy compartments.

“Or so everyone thought,”writes China-based lawyer James M. Zimmerman in “The Peking Express: The Bandits Who Stole a Train, Stunned the West, and Broke the Republic of China.” In the early hours of May 6, as Aldrich and her fellow travelers slept, a bandit crew of demobilized and unpaid soldiers, led by 25-year-old Sun Mei-yao, removed bolts from a section of track just south of the town of Lincheng, in Shantung Province, and caused the train to derail. Sun’s contingent of a thousand men swarmed the carriages, looting what they could and kidnapping more than 100 passengers, including 28 foreigners—most of them wearing little more than their nightclothes as they were led on a forced march into the darkness.

Mr. Zimmerman peppers his fast-moving narrative with colorful details and memorable characters among both the hostages and their captors. Aldrich was quick to scold the young outlaws as they steered her through the countryside, treasured family jewelry secreted in the toe of her slipper. Shanghai journalist John B. Powell soon emerged as a leader among the captives, negotiating with Sun’s ragtag followers and seeking to understand the impetus for their daring actions. Sun, charismatic and idealistic, is sympathetic in his frustration with the weak Peking leadership and the corrupt Shantung military governor, Gen. Tien Chung-yu, who had earlier had Sun’s brother killed to assert his control over the province.

The bandits led the captured passengers on a circuitous path eastward across southern Shantung. They stopped at a compound where they set up camp for nearly a week before proceeding to Sun’s stronghold at Paotzuku Mountain. News of the “Lincheng Incident” spread quickly around the world, setting in motion a flurry of diplomatic exchanges and attempts to parley with the kidnappers. As the days passed, Sun made clear his demands: the withdrawal of troops from Shantung and re-enlistment into the armed forces for his men.

Aldrich was among the hostages who managed to break off from the procession amid the haphazard trek. Sun and his main co-conspirator, Po-Po Liu, released other captives with messages conveying the terms under which the outlaws would settle. The Peking government refused Tien’s offer to resign from the province’s governorship, which only emboldened him. Tien’s armed forces continued to pursue the outlaw gang. Various foreign interlocutors attempted to intervene, including the American “fixer” Roy Anderson, who had grown up in China as the son of missionaries and served in the revolutionary army that had brought down the Qing Dynasty a decade earlier. Neither side showed any inclination to concede ground, and the hostage situation turned into a protracted standoff.

. . . .

On May 22, 1923, the government in Peking finally ordered Tien to stand down, making it possible to break the impasse. Sun eventually agreed to enter discussions, with Roy Anderson acting as intermediary. Slowly, haltingly, the negotiations progressed, until the final eight foreigners were freed after 37 days of captivity.

The foreign hostages, however, were small in number compared with the Chinese passengers taken prisoner and held until their release was negotiated a month later. Presumably due to limitations in source materials available to Mr. Zimmerman, “The Peking Express” focuses on the most notable foreigners, while the Chinese hostages are less distinguishable. The episode was of great import within China. “The proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back,” it precipitated the resignation of the government in Peking and marked the full-scale collapse of the country into feuding warlord factions for the remainder of the decade.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal

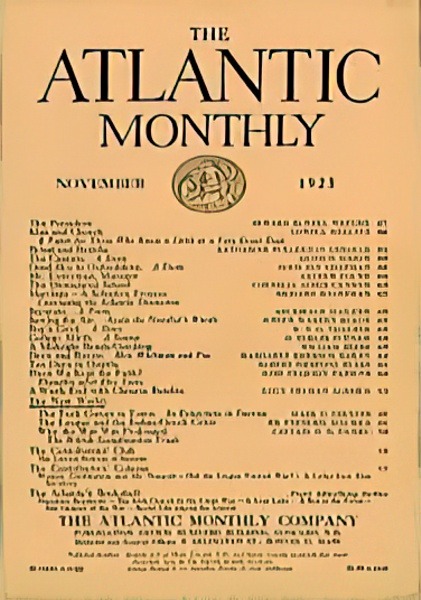

Here is the beginning of the original Atlantic article, published in November, 1923:

PEKING, CHINA

May 20. 1923MY DEAR SISTER,—

I suppose if I am ever going to write you about our adventure I’d better begin at once, as I am getting to the place where I want to put the whole thing out of my mind, for a while at least. Of course, for the rest of my life, when I am ‘ stalled ‘ conversationally, it will be a wonderful thing to fall back on: ‘Oh, I must tell you about the time I was captured by Chinese bandits.’ That remark, from a fat, domesticlooking old lady in a Worth gown, ought to wake up the dullest dinner party. I think I shall begin at the beginning and try to tell you everything as it happened.We left Shanghai early Saturday morning, taking a Chinese guide with us as far as Nanking, where we changed for the Peking train. We had so much hand luggage with us, we were afraid of losing it on the ferry. With a good deal of bustle and rushing around, we finallysettled down in two compartments on the Peking-Pukow express — Mathilde and I in one and Miss MacFadden in the other. The car was much the most luxurious I have ever seen in the East, quite the last thing in modern sleepingcars, more like the Twentieth Century Limited than Chinese.