From The Los Angeles Review of Books:

What if we remembered Jack Kirby not for Captain America or Galactus, but for the romance comics that he and Joe Simon produced during the late 1940s and early 1950s in their wildly successful titles Young Romance and Young Love? Kirby’s work in the genre, which he and Simon invented, are marked by Wellesian compositions and subtle character studies. They’re the equal of Kirby’s best superhero stories. Twenty thousand romance comics were printed in this period. One billion copies were sold.

Imagine an issue of What If…, Marvel’s late 1970s series imagining alternative timelines for their characters, in which the romance genre’s fans never disappear. In the 1960s, Kirby moves to Marvel and he and Stan Lee create a universe not of superheroes and mutants, but of heartthrobs who dress like Steve McQueen and strong women who look like Jean Seberg. In the mid-1980s, Frank Miller and Alan Moore produce gritty, revisionist graphic novels that revive the genre for a more cynical era. Moore’s Watchwomen tells the story of a dystopian America in which Richard Nixon vanquished the Vietnamese thanks to a romantic intrigue involving a Minnesota housewife and Võ Nguyên Giáp. Romance, the culture understands, is best suited to the comics medium, and supermarkets don’t sell romance paperbacks.

In the early 2000s, Hollywood, after several false starts, produces lush big-budget spectacles based on classic romance comics. Franchises are born. Film snobs compare the current crop of blockbusters unfavorably to the saturated melodramas of Hollywood’s Golden Age. “Where is our generation’s All That Heaven Allows? Our Written on the Wind?” they write in The New Yorker. “Cinema is dead.” But ticket buyers don’t worry too much about the elites’ complaints. The movies sell toys and video games and they do well in China. Comic-cons are dominated by fans who think they’re rebels for performing romance cosplay.

Academics hold conferences where they argue for the cultural legitimacy of the romance comics genre. Professors teach Chris Claremont’s classic run on Heart People alongside Pride and Prejudice. Salman Rushdie declares himself a fan of romance, and Michael Chabon turns his own fandom into a career. Romance comics face a reckoning in the 2010s, when a disgruntled fan base points out the genre’s long history of racism and sexism. The major publishing houses introduce a new set of romance comics heroes and heroines who are more representative of the country’s demographics. An alt-right backlash ensues, but Marvel, to its credit, keeps the new characters. Ta-Nehisi Coates and Roxane Gay contribute story lines about classic romance comics’ few black protagonists. Fantagraphics and Drawn and Quarterly, meanwhile, publish indie superhero comics read by only a select few. The spring box office in 2019 is dominated by the Russo brothers’ Young Romance: Growing Older and Closer to Death. Think pieces in The New York Times, NPR, Slate, and the Los Angeles Review of Books point out connections to the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, the war on terror, and climate change. Alan Moore declares the romance comics genre morally indefensible. Martin Scorsese makes superhero films.

In fact, it’s even more complicated than that. A society in which the culture as a whole reads romance comics is also a society more interested in women’s stories, and thus a society slightly less dominated by men. The industry includes more women creators. It is Margaret Atwood and Zadie Smith, not Rushdie and Chabon, who champion mainstream fare. Hillary Clinton is elected president in 1992 and proves just as inadequate as her husband did in another reality.

. . . .

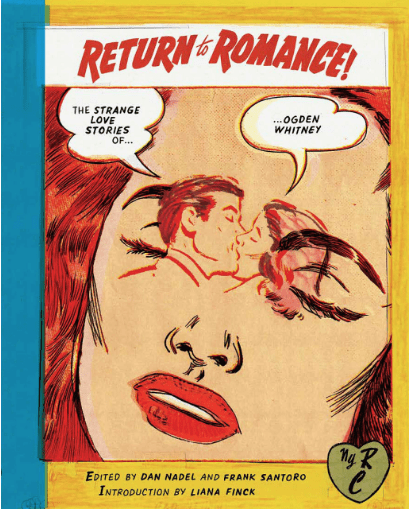

In our own world, only a very small percentage of vintage romance comics have been reprinted. And the few that you can find are advertised as exceptional, either for their aesthetics or their ideology. In 2003, Fantagraphics released Romance Without Tears, a collection of work written by Dana Dutch for the independent publisher Archer St. John. Several of these comics are drawn by Matt Baker, a gay, black man who was one of the few African-American artists of the comics’ Golden Age. John Benson, who spent years compiling the volume, argues in his introduction not so much for the stories’ aesthetic brilliance as for their proto-feminism. “Dutch’s protagonists,” as opposed to those in other romance comics, “were lively, active young women who, though often naïve and inexperienced, had character, a sense of self worth [sic], and a great deal of common sense.” In 2012 and 2014, Fantagraphics published Young Romance and Young Romance 2, a selection of Kirby and Simon’s work. In the introduction to the first volume, Michelle Nolan calls Kirby and Simon’s issues “some of the most dramatic and emotionally powerful comics of their time.” She also commends the creators for their qualified progressivism, noting that “[t]o this writer’s best knowledge, Simon and Kirby dealt with virtually every type of social issue except the still-forbidden interracial romance.” Twenty-first-century readers accept, even celebrate, this sort of didacticism. Comics should be nutritional, they say. They should make us good, or at least less bad.

. . . .

Romance, by definition, is a genre in which women live to find love. If they didn’t, these stories would not exist.

Link to the rest at The Los Angeles Review of Books