From Long Reads:

Angeline Allen must have been pleased. On October 28, 1893, the 20-something divorcée, an aspiring model, made the cover of the country’s most popular men’s magazine, a titillating journal of crime, sport, and cheesecake called the National Police Gazette. Granted, the reason wasn’t Allen’s “wealth of golden hair” or “strikingly pretty face,” though the magazine mentioned both. Rather, the cover story was about Allen’s attire during a recent bicycle ride near her Newark, New Jersey, home. The “eccentric” young woman had ridden through town in “a costume that caused hundreds to turn and gaze in astonishment,” the Gazette reported.

The story’s headline summed up the cause of fascination: “She Wore Trousers” — dark blue corduroy bloomers, to be exact, snug around the calves and puffy above the knees. “She rode her wheel through the principal streets in a leisurely manner and appeared to be utterly oblivious of the sensation she was causing,” according to the reporter.

It is unlikely Allen was truly oblivious, having already shown an exhibitionistic streak over the summer when she appeared on an Asbury Park, New Jersey, beach in a bathing skirt that “did not reach within many inches of her knees,” according to a disapproving newspaper report. (“Her stockings or tights were of light blue silk,” the report added.) Allen didn’t mind people noticing her revealing outfits — “that’s what I wear them for,” she told one reporter — and she kept cycling around Newark in pants despite the journalistic scolding. As another paper reported that November, “The natives watch for her with bated breath, and her appearance is the signal for a rush to all the front windows along the street.”

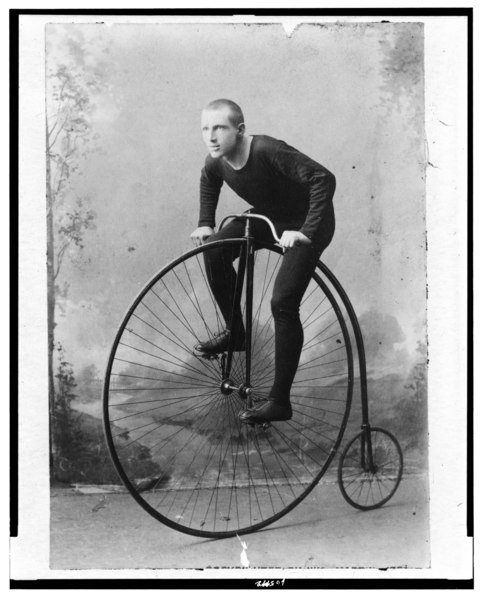

For a grown woman to reveal so much leg in public was a staggeringly brazen act. What was noticeably unnoteworthy by then was Allen’s choice of vehicle. Ten years earlier, all bicycles had been high-wheelers, and riding one had been largely the province of daring, athletic men. The women who had attempted it were seen as acrobats, hussies, or freaks; one female performer who rode a high-wheeler in the early 1880s was perceived as “a sort of semi-monster,” another woman reported. But by the early 1890s, the bike had undergone a transformation. Allen’s machine — a so-called safety bicycle — had two thigh-high wheels; air-filled rubber tires; and rear-wheel drive, with a chain to transmit power from the pedals. In fact, it looked a lot like a 21st-century commuter bike, and it had become nearly as acceptable as one. Even the fashion police who scorned Allen’s riding outfit didn’t object to her riding.

. . . .

It wasn’t just that women enjoyed the physical sensation of riding — the rush of balancing and cruising. What made the bicycle truly liberating was its fundamental incompatibility with many of the limits placed on women. Take clothing, for example. Starting at puberty, women were expected to wear heavy floor-length skirts, rigid corsets, and tight, pointy-toed shoes. These garments made any sort of physical exertion difficult, as young girls sadly discovered. “I ‘ran wild’ until my 16th birthday, when the hampering long skirts were brought, with their accompanying corset and high heels,” recalled the temperance activist Frances Willard in an 1895 memoir. “I remember writing in my journal, in the first heartbreak of a young human colt taken from its pleasant pasture, ‘Altogether, I recognize that my occupation is gone.’” Reformers had been calling for more sensible clothing for women since the 1850s, when the newspaper editor Amelia Bloomer wore the baggy trousers that critics named after her, but rational arguments hadn’t made much headway.

Where reason failed, though, recreation succeeded. The drop-frame safety did allow women to ride in dresses, but not in the swagged, voluminous frocks of the Victorian parlor. Female cyclists had to don simple, “short” (that is, ankle-length) skirts in order to avoid getting them caught under the bicycle’s rear wheel. And to keep them from flying up, some women had tailors put weights in their hems or line their skirt fronts with leather. Other women, like Angeline Allen, shucked their dresses altogether and wore bloomers. The display that reporters had deemed shocking in 1893 became commonplace just a few years later as more and more women started riding. “The eye of the spectator has long since become accustomed to costumes once conspicuous,” wrote an American journalist in 1895. “Bloomer and tailor-made alike ride on unchallenged.” (For her part, Allen may well have given up riding, but not scandal; she progressed to posing onstage in scanty attire for re-creations of famous paintings, a risqué popular amusement.)

Link to the rest at Long Reads

There’s no way to not look ridiculous on one of those bikes, but I’m certain trousers would look slightly less ridiculous than a dress.

This historical shock at a woman wearing something that shows she has two legs always makes me wonder if boys back then went through a period of believing that women were monopods or perhaps ran on tracks.

This guy gives a good demonstration, although he mostly talks for the first half of the video. He does explain how you have to counter pull your downward thrust with the opposite hand. Also, classically, no brakes, although I expect that in the 1890s there was much less traffic to brake for.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UImiYy44rRE

Of course “She Wore Trousers”, could you imagine trying to ride that thing in a dress? (Or what kind of show a gal would put on if she tried? 😉 )

Never understood the big wheel bikes, any hill would stop/kill you.

Direct drive to the front wheel – and no gearing to increase torque. Without the huge wheel, you would barely move (if at all).

Before rubber tires were added, the bigger wheel also helped some to cushion rough roads. Bicycles with a front wheel only slightly larger than the rear one were called “bone shakers.”

http://www.oldbike.com/Boneshakers02.jpg

(That picture shows a lady on one of them – apparently you could ride one with a skirt on, although not all the way down to the ankle. I think those are bloomers underneath it, too.)