From The Wall Street Journal:

In the spring of 1949, the press baron Viscount Rothermere gave a ball that defied Britain’s postwar decline. The men wore white tie, the women their family jewels. The Queen Mother was there, and so was the royal of the moment, Princess Margaret. Late that night, the princess, giddy with Champagne, took the mic from Noël Coward and delivered her party trick. Her Royal Highness began to sing, off-key and out of time. The revelers loyally cheered and called for more.

Margaret was just beginning to mutilate “Let’s Do It” when a “prolonged and thunderous booing” emerged from the crowd. The band stopped, and the princess reddened and rushed from the room. “Who did that?” Lady Caroline Blackwood asked the man at her side. “It was that dreadful man, Francis Bacon,” he fumed. “He calls himself a painter but he does the most frightful paintings.”

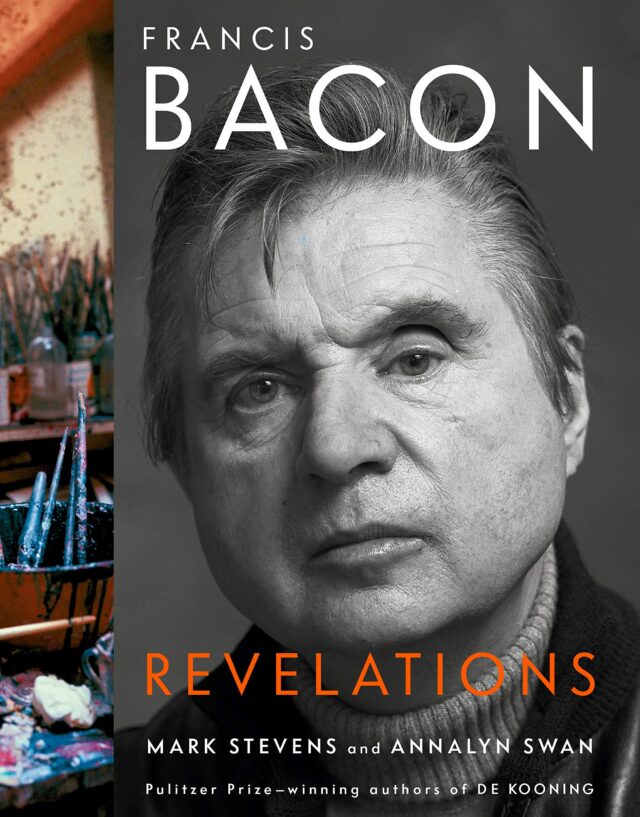

More than a decade before the end of the “Lady Chatterley” ban and The Beatles’s first LP, the iconoclasm of Francis Bacon announced a new era in British life. By his death in Madrid in 1992, Bacon was a social and artistic icon, his battered face the image of painterly tradition. Openly gay, he was the king of Soho, a nocturnal drinker and cruiser, his motto “Champagne for my real friends, real pain for my sham friends.” By day, alone in his studio, he was the exposer of torn flesh and gaping mouths, of the secret shames and spiritual collapse that, in the postwar decades when French thinkers ruled in concert with French painters, made him the only truly English existentialist.

With “Revelations,” Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan enter a biographical field as crowded as the Colony Room on a Friday night. Almost all the revelations are already revealed: the Baconian literature includes testimonies from Bacon’s critical patron David Sylvester; his fellow artist and slummer Lucian Freud; his drinking friend Dan Farson; and his assistant Michael Peppiatt. Mr. Stevens and Ms. Swan might, like Bacon’s friends, share a tendency to confuse the man with the art—like Oscar Wilde, Bacon was his own best work—but they bring a sober eye and an organizing mind to Bacon’s “gilded gutter life.” As in their acclaimed “de Kooning,” the authors frame their subject and his work as a portrait of the age.

. . . .

Erratically educated, Bacon “wasn’t the slightest bit interested in art” until 1930.

. . . .

Almost entirely “self-taught and untouched,” Bacon turned to painting. A critic mocked his first publicly exhibited portrait as “a tiny piece of red mouse-cheese on the end of a stick for head,” and he was judged “insufficiently surreal” to be included in London’s International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936. He and Nanny Lightfoot survived by holding illegal roulette parties.

. . . .

The war made Bacon. The revelatory evils of Nazism, the bombing and the newsreels of the death camps all forced the public to acknowledge the horror and the moral vacuum from which it had emerged. The critics, too, realized that Bacon had “found the animal in the man and the man in the animal.” A magpie for quotations and influence, Bacon liked to quote Aeschylus: “The reek of human blood smiles out at me.”

From then on, Bacon was famous and rich, unless he had lost at the tables. The authors excel at illustrating his formation—Bacon destroyed almost all his early work—his manipulation of his image and value, and his helpless gambling in the power games of love. He believed in beauty and tragedy, and he got and gave both.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal

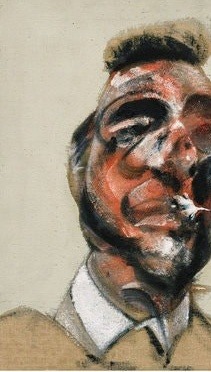

PG includes a portion of one of three panes in a triptych for those unfamiliar with Bacon’s work. PG expects that the virtues of Bacon’s artistic sensibility may be a learned taste for some.