From Buzzfeed News:

Five years ago, Kathleen Hale wrote an essay for the Guardian — about targeting a Goodreads reviewer — that nearly ended her career. Now, she’s back with a new book that some people say never should have been published.

. . . .

When you start writing professionally, namely about yourself, people don’t really tell you that putting that kind of work out into the world can feel dangerous. Dangerous to your sense of safety, dangerous to your sense of self, to your relationships, and perhaps even to any potential future career. Write the wrong thing — and here, wrong can mean anything from merely obnoxious to cruel or racist or wildly incorrect or otherwise offensive — and it’s easy to be misunderstood, or eviscerated online, or fully canceled, whether for good reason or not.

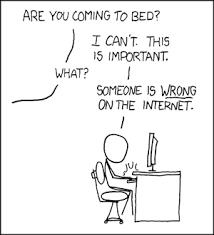

This fear has only become exacerbated by constant online feedback. While literary backchannels have always shared negative book reviews, dreaded one-star Goodreads reviews now keep authors up at night, adding to that feeling that everyone can witness (and contribute to) your public failure. Plus, no one likes being the center of a Twitter pile-on, even when it might be ultimately deserved. We’re all waiting for someone to tell us we’ve written something that failed — and we’re all anxious about how devastating the consequences might be.

Which is why, perhaps, the author Kathleen Hale has become a representative for a worst-case scenario of what can happen when someone writes something that has been deemed “wrong.” But Hale’s story is not just about a singular personal disaster — it also speaks to the nature of criticism today, so-called cancel culture, and the growing power of Goodreads, especially for emerging genre writers.

In January 2014, Hale was a 27-year-old freelance journalist and essayist, living in New York with one recently released YA book and a second under contract with HarperCollins. Her debut, No One Else Can Have You, was considered controversial for a book marketed to teenagers. The dark comedy, which included references to murder and abuse, raised the ire of some reviewers online — including on Goodreads, an online community that has become a major driver of book publicity, where anyone can leave reviews of nearly any book. Hale wasn’t a household name, and her book wasn’t tracking to be among the most popular YA books to be released that year, so she followed her publisher’s advice to be more online and spent the next few months writing a handful of pieces in hopes of getting her name out there. (She underestimated how well this would work — for all the wrong reasons.)

And then Hale did something that ruined her literary career before it ever really hit its stride. You’d be forgiven if you don’t remember the exact details of that particular five-year-old internet spiral. It began with an October 2014 Guardian essay about confronting an unfriendly Goodreads reviewer.

. . . .

But it wasn’t just that Harris didn’t like Hale’s book; it was that she was encouraging others to avoid it as well. “Other commenters joined in to say they’d been thinking of reading my book, but now wouldn’t,” Hale wrote in the Guardian essay that documented her obsession with Harris’s review. “Blythe went on to warn other readers that I was a rape apologist and a slut shamer. She said my book mocked everything from domestic abuse to PTSD.” (In an updated version of the essay in her new collection, she adds, “She’d only read the first chapter, she explained, but wished Goodreads allowed users to leave scores of zero, because that’s what my novel deserved.”)

. . . .

“The internet kind of drove me crazy in 2014,” Hale told me over the phone, in one of two interviews in late May. “I think that my experience is on a continuum of what normal people experience online. I think even the healthiest people are driven a little mad by the internet.”

Not only did Hale start digging into Harris’s social media presence, but once she discovered Blythe Harris was not who she said she was — according to Hale’s investigation, she was not using her real name and had taken photos from another woman’s Facebook page — she also paid for a background check to find out where she lived, aided by an unwitting assist by a book club who forwarded her Harris’s address after Hale said she wanted to do a Q&A with her. Hale then rented a car and drove to what she believed was Harris’s house. She didn’t end up making physical contact, but called the person who lived at the residence, pretending to be a fact-checker in hopes of figuring out Harris’s real identity.

Hale felt that Harris’s assessment of her book wasn’t just hurtful, it was wrong.

Link to the rest at Buzzfeed News

Amazon bought Goodreads a few years ago, in someone failed to notice.

Apparently they’re fine with how it’s being run.

People noticed…but it was too late.

It was their best defensive move this side of Buying Audible.

If somebody else had bought Goodreads and added book-buying links they’d be Kingmakers.

Instead, Amazon made sure it remained all talk.

It was a brilliant move. It left Amazon in control of the world’s two largest collections of reviews.

Writers are weird.

Narcissistic enough to believe they should put their writing out in public for the world to see, and arrogant enough to think they should even get paid for the privilege, too.

But at the same time so insecure and thin-skinned, in many cases, that they react to criticism by either curling up in a thumb-sucking fetal ball, or lashing out with infantile vindictiveness.

I get (and approve of) the first part, but not the contradictory second part, which I never understood.

The psychology just seems alien.

All true.

They go hand in hand. Lots of Ego (Asimov said the same decades ago) but it is thin-skinned, as if perpetually waiting for the other shoe to fall.

Best explanation I can think of is lack of reliable feedback. The fear good news isn’t honest and bad news comes with ulterior motives. This would be especially true of the tradpub/legacy crowd who followed the “Grafton Model” of writing and “trusting the universe to take care of them. All they ever see is one agent (out of dozens?) who didn’t reject their manuscript and one publisher who threw out a bit of coin to put it out for the world to see. Neither is really a great endorsement, regardless of the words it comes wrapped in. In the back of their mind it seems many authors see themselves as frauds and so see any nay-saying as the beginning of their end.

Indies *should* be free of this but they are working in a smaller, more heavily contested market and seem to fear being the flavor of the month. With similar reactions.

One thing I do know: being a commercial writer is a long haul endeavor. And in any long term operation there will be ups and down, peaks and valleys. Some things will work, some won’t. Short term variation will cancel out over time. It’ll take years to decades before you have enough data to be able to conclusively say: I know what I’m doing and there is a market for what I do.

Few have the true strength of ego to stay level throughout all that. It takes experience and lots of it. And right now there hasn’t been enough time in the New Epoch of publishing for anybody to accumulate the necessary experience to be able to conclusively say whether *anything* is good or bad or to what extent. Even the short term Indie successes are angsting.

Serene acceptance is in short supply.

But at the same time so insecure and thin-skinned, in many cases, that they react to criticism by either curling up in a thumb-sucking fetal ball, or lashing out with infantile vindictiveness.

Are authors unable to write about their product without infantile vindictiveness?

In non-fiction journals we see authors engaging with reviewers all the time. A guy writes an article, and the next month, the letters section has critiques of his article. The editors provide the critiques to the author, and the author answers the criticism immediately below. This can go on for several months, and is often much better than the original article.

Claremont Review of Books is an excellent example.

It’s a well established practice. I don’t know why we should think fiction writers and reviewers can’t do the same.

If you’re a commercial writer, the most important review is the “Dan Brown Cha-ching Review”.

Nothing will ever satisfy everybody so just make sure you satisfy enough readers to move forward.

just a placeholder comment so I can monitor this post

For me, Good Reads is a place for readers, period. I just went on and checked our 2 pen names and was delighted with the hundreds and hundreds of four and five star ratings for our books.

Don’t get me started about the drive by one star reviews left, or any of the nonsense. Yeah, it hurt like hell years ago, but now after being in this game for a while I don’t even bother reading them.

I NEVER go on there to say one word about our stuff, and the author profiles state that if one wants contact to send an email. I do go on in my IRL name to get suggestions for other books in genres I enjoy beside our own. I’ve found some great new authors that way. So as a reader, yeah, it’s pretty cool.

About a year ago I left a glowing review of a book there and was contacted w/ a thank you note from the author. I wrote back and told him ‘I wasn’t trying to communicate with you, I was talking to other readers’. I then explained that I too made my living as an author, and my policy is to never engage a reader via the review page. Sure, I reply (most of the time) to emails, but I don’t belong within a million miles of review pages.

That’s my take as well. Review space is a reader’s space.

Some users would like to reserve someone else’s site for themselves, and have others stay away. There is no reason to care what they want.

I fondly recall a group of TPV users a few years back who decided I should stay away because of my political and economic views. They had determined who should comment, and who should not.

Did you reply to the wrong comment?

EDIT: Oh I see you edited. I get it. Yeah, we aren’t saying that. We are saying there’s nothing to be gained by a writer engaging in the review space with reviewers.

I did indeed get mixed up in cut and paste from another site, and tried fix it as soon as I could.

In terms of the issue, Orsen Scott Card gained a fan when I read his reply to reviewers on Amazon. I thought it was great.

I’d say some people like to read authors engaging with reviewers, and some don’t. That’s just personal taste and preference. I don’t think we have sufficient data to say an author gains or loses by the practice. My own speculation is that it depends on how he does it.

My preference is for them to engage, but my preference isn’t anywhere near sufficient data to form a conclusion.

And God Bless the ideologues, for yesterday was another day.

I deleted my posts.

I’m not up for a flame war. Not today.

As a reader, I am often pleased when authors engage with my reviews of their work, and I enjoy watching authors interacting with their readers without vitriol. It is possible.

My personal experience has been that all the readers I’ve chatted with about their reviews have enjoyed talking with me about them, but I tend to leave the people who disliked things alone because I get the feeling they’d prefer that. But there’s no harm in “hey, glad you liked it! You picked up on this really cool thing that I put in the text just for people like you” or “yes, the sequel you mentioned hoping for is out next month!”

*spreads hands*

But I don’t think ‘author’ is some special, protected class. I write books, but I also read them, and I consider myself part of the community of people who love books. *shrug*

I remember that era of TPV fondly. Lots of big names came here to discuss the indie news of the day.

But we failed to push out the argumentative ideologues, like yourself, and this place was gutted. Good job, you won.

I remember that era of TPV fondly. Lots of big names came here to discuss the indie news of the day.

But we failed to push out the argumentative ideologues, like yourself, and this place was gutted. Good job, you won.

Exactly. A subset of people don’t want to be exposed to ideas they disagree with. Rather than engage ideas, the practice has become to try to suppress the ideas, push them out.

There is a notion that ideas which make an individual uncomfortable, should be suppressed so the individual doesn’t have to be uncomfortable. We also find the corollary that ideas which offend me should not be seen by anyone.

Justice Gorsuch touched on the general issue yesterday in a concurring opinion in Mont v United States. He writes, “Really, most every governmental action probably offends somebody. No doubt, too, that offense can be sincere, sometimes well taken, even wise. But recourse for disagreement and offense does not lie in federal litigation.”

Note Ginsburg and Sotomayer dissented, and presented cogent and well-reasoned counter argument.

Nope. 100% wrong. Delusional even.

Your silly ideas don’t drive people away, it’s that you camp threads and fire off multi-paragraph rebuttals all day. Successful people don’t have time to engage at that level with random internet warriors.

So you’ve won a game no one was even playing. Casting yourself as the free speech hero. Bravo warrior!

I’d always heard the advice “Don’t read bad reviews” and that seemed reasonable, but then someone said, “Don’t read the good reviews either. They’ll get in your head and mess up your writing.” Which makes a lot of sense as well.

Do we have any data about the effect of Goodreads on actual sales?

How about data on the percentage of book buyers who read Goodreads reviews?

Well that’s the issue.

One side of the discussion says goodreads is a terrible site filled with people who are just waiting to destroy your reputation, the other that goodreads is the best thing for authors and that every author should be on it, both seem to give good reads more of an impact than it deserves.

Honestly, just ignore the site, I don’t have any sympathy for authors who complain because mostly they get themselves into the situation in the first place by reading the reviews there and then thinking that this represents the views of the general public, when in reality sales are the only metric that is reliable.

Like anything, I suspect it depends on the community. Moderated book groups on Goodreads seem to be nice places to discuss books and share new finds. As a reader, between those recommendations and their algorithm it’s a great place to find new books. As an author, getting into discussions about what you meant to say or what something really means sounds like the worst kind of bad idea.

These goodreaders panning and seeking to cancel her books need to chill. That was 5 years ago, she’s seen the error of her ways, and I doubt she’ll repeat that performance. What the goodreaders are doing is becoming even worse than what she did, as hers was a one-off and they keep doing it. They’ve stalked/doxed her in return and cost her books sales. Why is that not punishment enough for her 2014 looniness?

I remember reading about what this author did years ago and felt the burn against her for it, but let it go, people, let it go. The way Hale should have and didn’t. Now, you guys are being the villains.

Seriously, reviewers are out of control. They’ve become mobs, unforgiving mobs.

Rule #1: Never, ever, go on Goodreads.