From ArtNews:

In New York’s Southern District Court on Monday, lawyers for the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and photographer Lynn Goldsmith stood before Judge John G. Koeltl in service of their clients in a case taking up a 1984 series of Warhol screenprints of the storied musician Prince.

. . . .

Goldsmith has alleged that Warhol copied an image she took of Prince in 1981 and, in doing so, violated her copyright. She shot her image of Prince while on assignment for Newsweek, and Warhol used her image for “Prince,” a series of 16 screenprints he made in 1984.

The Warhol Foundation first filed a preemptive motion against Goldsmith’s claim in 2017, alleging then that she was attempting a “shake down.” As the case has continued, the foundation is now demanding a “declaratory judgment” to the effect that Warhol did not infringe upon the photographer’s copyright.

The case takes up complicated issues surrounding art and appropriation. Did Warhol artfully reconstitute Goldsmith’s image, or did he merely copy it? How could one side prove its position either way?

. . . .

Luke Nikas . . . attempted to address such questions. He said that, however similar they might appear, Warhol and Goldsmith’s representations of Prince serve different purposes. “Andy Warhol took images of people, goods, and companies to force us to confront how we consume them,” Nikas said—adding that, as viewers, “we’re not consuming Prince the person or the icon—we’re consuming the image.”

. . . .

Nikas suggested that “Goldsmith conveyed no intent to deal with the same topics as Warhol,” adding that their work was made for “entirely different purposes.” The judge concurred, asserting that if one were to put the two prints next to each other, the “common person would point to one and say, ‘Hey, that’s a Warhol!’ So that is its own work of art.”

Lawyers from both sides debated the “protected elements” of Goldsmith’s photograph—formal aspects of it that involved creative choices, such as lighting, color palette, angle, and cropping. Nikas argued that the Warhol work differed from Goldsmith’s photograph in all these respects. Goldsmith’s lawyer . . . said another protected element ought to be considered—that Warhol’s work did itself appear in Vanity Fair in 1984, meaning that it, too, could have been made for a magazine. Judge Koeltl disagreed with Werbin’s assertion, noting that the Warhol “Prince” works were art objects originally and not intended for editorial use.

Link to the rest at ArtNews

PG will note that he doesn’t think the reporter from ArtNews has spent much time in court prior to this case.

PG interprets the quotes from Judge Koeltl as reflecting that he doesn’t spend much time on cases of interest to anyone beyond police reporters and hopes to become the go-to guy for cases involving famous artists.

As Judge Koeltl deliberates whether Warhol’s portraits of Prince are the dynamic works of art they clearly are, it remains that these 16 distinctive portraits are a highlight of Warhol works from the 1980s . Having had the opportunity to see five of the paintings close up over the years, I can share that each work is very different, and unique within his later works as Warhol returned to a style for Prince he had developed over twenty years before, with his Marilyn flavor portraits. Each portrait of Prince I have seen conveys a similar punch and poignance as with Warhol’s Marilyn works, which is deliberate and the core point here.

I am Lynn Goldsmith’s counsel and argued the case. The ArtNews article upon which this report is based was inaccurate on several key points. First, it depicted the wrong Goldsmith photo in issue in the case, which in fact is an unpublished black and white (not color) close portrait of Prince, which is obvious from Goldsmith’s counterclaim for infringement and the court papers. Second, Judge Koeltl did not “disagree” with me vs. us having had an intellectual discussion and my focusing on the fact that Vanity Fair had licensed Goldsmith’s photo specifically to use as an artist reference, and Vanity Fair then commissioned Warhol to create one illustration for a 1984 article on Prince based on the Goldsmith black and white photo. So the targeted editorial magazine market was the same for both.

Fact checking used to be the norm in journalism.

Thanks for the detail, Barry.

About the reporter of the story: Or perhaps he thought it was a silly, uninteresting story, but his editor assigned it to him anyway. Reporters often have no say in what they cover.

As a photographer, I’d say:

1) The hair is too identical for chance, all around the head, including the jawline in question.

2) The apparent “different angle” is really only filling in the visible jawline on our left which is illuminated out in the photo.

So, yes, I’d say the one is definitely based on the other, with modifications.

I’m looking at the hair, which is, for the most part, identical between the pictures. Since that style is more or less random, chances of it appearing like that twice in a row would seem small.

That said, once you change a picture that much, a claim could be made that it’s a new copyrightable work in itself.

I see the case is pending. I’m guessing the judge will side with Warhol and his “reconstituted” work.

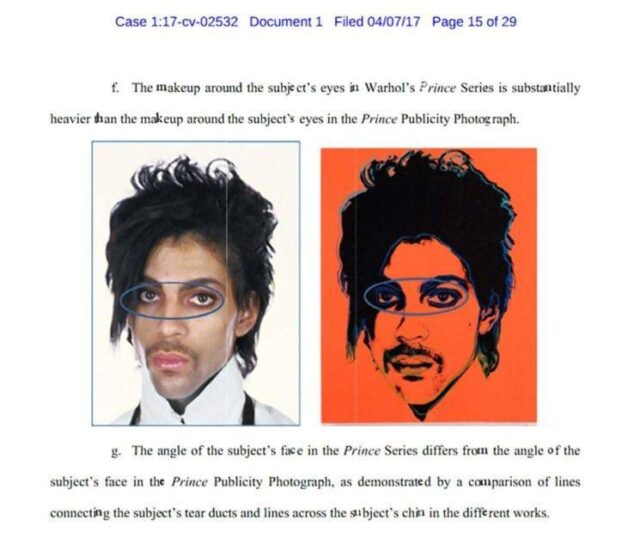

PG’s example from the case of the “differences” shown in the graphic above (f) did make me laugh. The “makeup is substantially heavier”? Anyone who’s worked with images going to high contrast knows that the shadows go to black with a “litho” treatment. I used to do tons of these myself in the ’60s-’70s. It was quite trendy. Even sold a few.