From The Literary Hub:

I keep a bulging plastic bin under my bed filled with diaries I’ve had since elementary school. They are an archive of my life, literal baggage I tote around from apartment to apartment as an adult. The notebooks are proper diaries covered in girlish stickers and locks, extra composition books from school, soft leather-bound books, and Moleskines.

Every year of my childhood, I spent the summers alone, feasting on library books and the occasional teen magazine I convinced my grandmother to buy me at the grocery store. I had my first panic attack at 13: a sweaty nighttime episode where I cried for hours, scared that I wouldn’t ever connect with another person again, terrified that I might not exist. I used my diaries to record those days as they passed, to prove to myself that I had lived through them.

When I was in seventh grade I discovered MySpace and began uploading my consciousness to the internet. My notebooks from that period remained blank; instead, the Internet was my scrapbook, my diary, my platform. I eventually graduated from MySpace to Facebook, then to Twitter and Instagram. I kept a blog throughout my college years and used it to puzzle out my identity to a modest audience of friends and family. It was a record of myself, of my adolescence. It was proof that I existed.

For a long time, much of what I consider my legacy, my footprint on this world—photos, new job announcements, stupid observations about the world—existed only on the Internet. It wasn’t until recently that I thought that might be a problem. Because that archive of my life that I tote from apartment to apartment has a gap in it that starts in 2005 and ends in 2014—and my writing from those years is lost forever.

. . . .

Schwartz is the host and producer of Preserve this Podcast, an initiative from the Metropolitan New York Library Council to educate podcasters about the threats of digital decay. She told me that most people think digital files are protected forever simply because they’re online. In fact, that couldn’t be further from the truth.

“Digital is about access, it’s about sharing,” Schwartz said. “But once you digitize something, suddenly the object is not human-readable anymore—not readable like a stack of letters in your attic. With digital you have to preserve the letter, and you have to preserve the software, and the machine that can read it.”

That means that as technology evolves, the types of data it can read evolves as well. Think about the floppy discs you almost definitely have in a box somewhere—or DVDs, to pick a more recent example. My current laptop doesn’t have a CD/DVD drive at all. I couldn’t watch my Mona Lisa Smile DVD if I wanted to. So you can see how delicate that media is.

Last month, MySpace announced that it had lost twelve years’ worth of photos, videos, music, and blog posts due to a fluke in server migration. Suddenly, a significant chunk of my own diary, my personal archive from my tenderest high school years, was gone. The Internet Archive has since come to the rescue of the hordes of musicians who lost their work, preserving 450,000 songs originally posted to MySpace. But my own “insignificant” work wasn’t preserved.

Link to the rest at The Literary Hub

Ever since the dawn of time when humankind began to walk upright, PG started using a personal computer, and that computer ate a document he had spent a lot of time creating, he has been pretty OCD about preserving some sorts of documents, photos, etc.

Slightly after the dawn of time, PG worked for a large company named LexisNexis that made most its money by providing electronic information to a variety of corporate and legal professionals. At the time, LN had the largest electronic database of legal and business information in the world (PG just checked the corporate website and LN says it currently has “3 petabytes of legal and news data with 65 billion documents. That’s 150 times the size of Wikipedia and doubling every three years.”)

At the time, the company’s data center was built so a car bomb larger than any known to have previously existed could explode right outside the building without destroying what was inside. Among the many backup strategies LN employed, one of its practices was to make a daily digital backup of its entire collection of databases and send one copy north and another copy south for storage in distant secure storage facilities.

While paper documents described in the OP are not subject to computer crashes, here’s what The National Archives (of the US) suggests for preserving paper documents and photographs:

Store items at a low temperature and a low relative humidity

- The lower the temperature the longer your items will last, because cooler tem

- peratures slow the rate of chemical decay and reduce insect activity. Keep the temperature below 75 degrees Fahrenheit (F).

- Keep the relative humidity (rH) below 65% to prevent mold growth and reduce insect activity.

- Avoid very low relative humidity because relative humidity below 15% can cause brittleness.

Reduce the risk of damage from water, insects, and rodents

- Store items out of damp basements, garages, and hot attics.

- Keep items away from sources of leaks and floods, such as pipes, windows, or known roof leaks.

- Store items on a shelf so they don’t get wet.

- Store items away from food and water which are attractive to insects and rodents.

Packaging family papers and photographs for storage. Boxes, folders, rolls, sleeves, albums, and scrapbooks, oh my!

Use containers that:

- Are big enough for the originals to lay flat or upright without folding or bending

- Are the right sizes, so items don’t shift

- Use a spacer board if there are not enough items to fill an upright box.

- Don’t overstuff the box.

- Are made of board or folder stock that is lignin-free and acid-free or buffered.

- Have passed the PAT if storing photographs

Link to the rest at The National Archives

“What,” you may ask, “is the PAT?”

From The Image Permanence Institute:

The Photographic Activity Test, or PAT, is an international standard test (ISO18916) for evaluating photo-storage and display products. Developed by IPI, this test explores interactions between photographic images and the enclosures in which they are stored. The PAT is routinely used to test papers, adhesives, inks, glass and framing components, sleeving materials, labels, photo albums, scrapbooking supplies and embellishments, as well as other materials upon request. This test can be performed on products in development as well as on materials already in use in collections.

. . . .

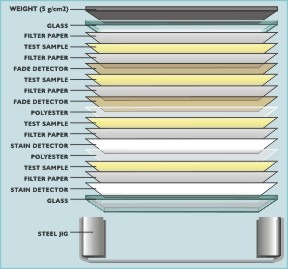

Materials to be tested are cut to size and stacked in contact with image interaction and stain detectors. The stacks are held together in a stainless-steel jig. A control stack is prepared using an inert material in place of the test sample. These stacks are then incubated in a temperature- and humidity-controlled chamber to simulate aging. Once incubation is complete, the jigs are disassembled and the samples’ image interaction and stain detectors are assessed for changes in density and compared to those of the control sample. Pass/Fail certificates are issued for each sample tested. The pass/fail limits have been derived from enclosures that are known to have caused fading or staining in real-life storage situations.

Link to the rest at The Image Permanence Institute

The Image Permanence Institute also provides a helpful illustration of the device and materials they use for the PAT test.

And, no, PG has no long-term storage strategy for the contents of TPV.

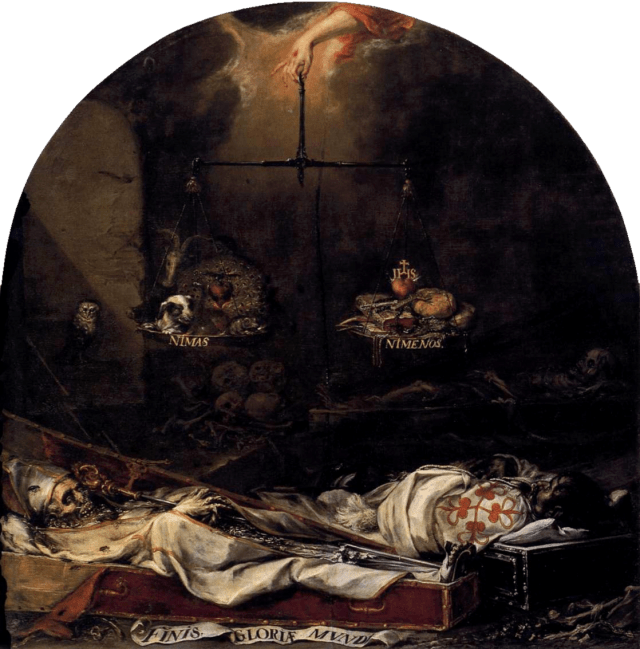

Sic transit gloria mundi

Speaking of upbeat Latin phrases, Wikipedia helpfully has an image titled, Finis Gloriae Mundi, which evidently hangs in the Hospital de la Caridad (Seville) to cheer up the patients.

Very useful info. Thanks.

That’s a fascinating painting. But if I were in that hospital, I’d want out of it ASAP!

Interesting further reading about the painting…

http://caravaggista.com/2011/10/on-halloween-remember-you-will-die/

You’re welcome, Deb.