From The National Law Review:

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed last week to review the Second Circuit’s decision that Andy Warhol’s well-known “Prince Series” was not a “transformative” fair use of the copyrighted Lynn Goldsmith photograph that Warhol used as source material (see Bracewell’s earlier reporting here).

The Second Circuit’s decision conflicts with the Ninth Circuit, and is potentially at odds with the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Google v. Oracle, which held that Google made “transformative” fair use of Oracle’s Java software language to build the Android smartphone platform. The Supreme Court upheld the Ninth Circuit’s ruling that the exact copying of computer code could be transformative if it “alter[ed] the copyrighted work ‘with new expression, meaning or message.’” Following Google, the Second Circuit issued a revised opinion in the Prince case that kept its original ruling and distinguished the Google decision as applicable to the “unusual context” of computer code. The high court is expected to settle the circuit split and provide much needed guidance on whether the Google ruling applies outside of the computer programming context.

The controversy arose when the Andy Warhol Foundation sued to fight allegations of copyright infringement from Goldsmith, a photographer who contended that she was not aware that Warhol had used her 1981 photograph of Prince until the music icon’s passing in 2016. A New York district judge ruled that Warhol’s series had transformed Goldsmith’s image from “a vulnerable human being” into an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Therefore, Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo did not constitute copyright infringement.

The Second Circuit rejected the district judge’s consideration of the intent and meaning behind the work, and found that the Prince Series was not a “transformative” fair use of the copyrighted photograph because it retained the “essential elements” of the Goldsmith photograph without “significantly adding to or altering” those elements.

Link to the rest at The National Law Review

In the United States, there are both federal courts and state courts. Generally speaking state courts in a given state focus on resolving disputes arising under the statutes of a given state, although some federal questions are occasionally mixed-in with state legal issues.

Federal courts typically deal with matters arising under federal law, although disputes between residents of different states can, under some circumstances, be filed or removed to federal courts, (“diversity jurisdiction”).

The large majority of all legal disputes in the US are resolved in state courts and there are many more judges in state courts than there are in federal courts. Dissolutions of marriage, for example, are virtually all resolved in state courts.

There are a handful of states which have their own limited copyright laws, but the serious copyright action arises under federal copyright law and is those fights happen in federal courts.

United States federal courts are in three tiers

- Federal District Courts are found in every state and that’s where disputes governed by federal law originate.

- Federal Courts of Appeal fall into 13 circuits populated by about 180 appellate judges. These circuits were established long ago and range from geographically small – the Second Circuit covers the district courts located in Connecticut, New York and Vermont. To the geographically enormous like the Ninth Circuit, which includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Oregon and Washington plus the District Court of the Northern Mariana Islands, a US commonwealth, governed by the US since the end of World War II.

- At the top of the Appellate Court hierarchy is the US Supreme Court, consisting of nine justices. As with all other federal judges, the Supreme Court justices are appointed for life.

The Supreme Court is required to hear appeals from a decision of one of the courts of appeal on some types of cases. With respect to other types of cases, the Supreme Court chooses which of the many appeals filed with them that the Court will accept.

The large majority of copyright cases end their lives in the Courts of Appeal. One of the more frequent types of cases the Supreme Court may accept is one where one or more of the 13 Circuit Courts of Appeal has/have issued decisions that conflict with decisions made by one or more of the other Circuit Courts of Appeal.

Conflicting appellate court decisions regarding the Warhol copyright case is likely the principal reason why the Supreme Court accepted it. The Supreme Court doesn’t specify why it accepts an optional appeal, but conflicts between the circuits with respect to something that is a major financial player in the US economy such as copyright protection likely impacted the Court’s decision. Computer code, movies, television and books are only a few of the many major US industries that rely upon copyright issues. Of the top ten largest US companies per Fortune magazine, three – Amazon (2), Apple (3) and Alphabet (AKA Google) (9) generate an enormous portion of their revenues via copyright-protected products and services.

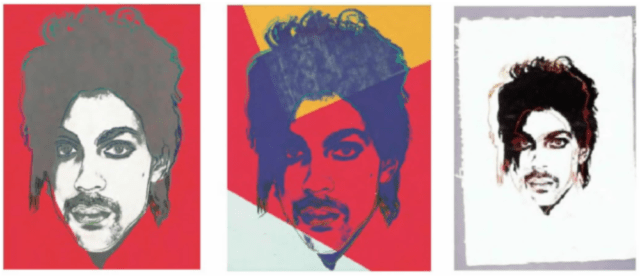

Here are small-form examples of some of the Warhol creations at issue in the above-described request for the Supreme Court to take the case.

This is a difficult case in which one reaches the copyright issues only after setting the stage with some contract issues. (I’m going just on how the judges have summarized the facts; that can be extremely dangerous and misleading, so don’t try this at home!)

The Warhol Foundation contracted with the photographer to create a single set of images in Warhol’s “famous” style. The contract specifically limited the number of reproductions and the nature of reproductions. WF greatly exceeded both. Goldsmith then sued; it’s in federal court on diversity jurisdiction (more than $75k at stake, different states) and because WF raised a copyright defense of fair use for which federal jurisdiction is exclusive.† So the real issue has three distinct steps:

(1) Were the restrictions in that contract enforceable in the first place? Goldsmith claims that it wasn’t a mere “later breach,” but intentional fraudulent inducement because WF planned all along to do a widespread exploitation and kept the price down by deceiving her as to its plans. If the restrictions are not enforceable, we can evade the fair-use issues.

(2) If the restrictions are otherwise enforceable, is fair use a defense to exceeding those restrictions? That is, does a defense afforded under copyright law act as a defense against a claim of breach of contract — especially when that particular defense is intertwined with both the First Amendment and trademark law, not just the literal/unaltered reproduction of a registered work?

(3) If fair use is a possible defense to exceeding the scope of the license, was this particular use by WF a fair use?

The activists — on all sides — are completely ignoring (1) and mostly ignoring (2), while simultaneously making slippery-indeed slippery slope arguments for no matter how this turns out.

† Well, not really. Both the Copyright Act itself and the Judiciary Act (28 U.S.C. § 1338(a), in particular) make jurisdiction over copyrights and interpretations of the Copyright Act exclusive in federal courts. But… states, and arms of the state, tend to claim Eleventh Amendment immunity (as in Chavez v. Arte Publico Press, which has some disturbing echoes of the Goldsmith/Warhol Foundation dispute). Then, too, there are purported “probate” and “family law” exceptions. It’s messy.