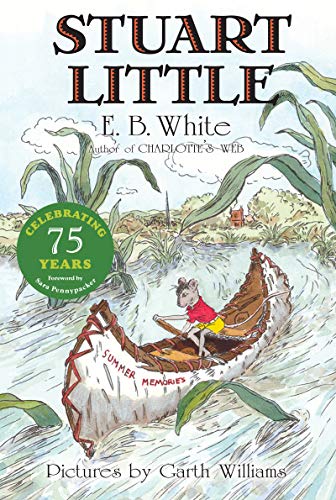

From Stuart Little:

In the loveliest town of all, where the houses were white and high and the elms trees were green and higher than the houses, where the front yards were wide and pleasant and the back yards were bushy and worth finding out about, where the streets sloped down to the stream and the stream flowed quietly under the bridge, where the lawns ended in orchards and the orchards ended in fields and the fields ended in pastures and the pastures climbed the hill and disappeared over the top toward the wonderful wide sky, in this loveliest of all towns Stuart stopped to get a drink of sarsaparilla.

Link to the rest at Stuart Little by E.B. White

This is also a sentence where the different clauses are all describing the same thing – “this loveliest of all towns.” Not a disjointed collection of impressions and actions as in the Wolfe snippet. That, to me, is what allows it to work.

Other writers out there – other than this “targeted” long sentence, when do you feel that this technique is valid? I can see two instances offhand, but I’m sure there are more:

1) When writing a “stream of consciousness under stress,” to communicate the disjointed and perhaps panicked thinking and emotions of the first person narrator.

2) In dialogue, when you have a character (hopefully not a main one) that is a “scatterbrain.” At least in their speech patterns.

I do use a disjoint sentence for the experience of characters under stress, to convey a visceral impression of their distress. I feel like that comes naturally. I am not tempted by the Wolfe example of cinematic bustle — I think that cinema does it much better than literature can (each form has its strengths).

But the E.B. White lyrical example is something I admire, rather than use– my fiction isn’t … in that “tone” (the best word I can think of) of quiet. My quiet is all in occasional conversations of unstated undercurrents, not in mood-setting description. My loss, no doubt — more tools for the toolkit.

I do use a disjoint sentence for the experience of characters under stress, to convey a visceral impression of their distress. I feel like that comes naturally. I am not tempted by the Wolfe example of cinematic bustle — I think that cinema does it much better than literature can (each form has its strengths).

But the E.B. White lyrical example is something I admire, rather than use– my fiction isn’t … in that “tone” (the best word I can think of) of quiet. My quiet is all in occasional conversations of unstated undercurrents, not in mood-setting description. My loss, no doubt — more tools for the toolkit.

Comparing this to the Tom Wolfe example upstream, look at how the lyrical description is summarized at the end (“in this loveliest of all towns”) into a simple phrase so that the reader does NOT have to go back and reread to remember how this sentence should be parsed. The reader’s trance is not disturbed and he leaves smiling instead of half-irritated.

Now THAT is lovely writing with a long sentence, keeping the reader in mind, and not self-indulgent the way the Tom Wolfe example is.