Continuing a Thanksgiving weekend reprise of the most popular earlier posts.

Once more, Passive Guy dips into his Contract Collection for another little horror. (What?! You haven’t contributed to PG’s Contract Collection yet? Click HERE to mend your ways!)

PG doesn’t disclose who, what or where regarding the sources for his contracts and he has modified today’s tidbit to maintain the anonymity of its sources.

While the paragraph heading says, “Conflicting Publications,” it’s really a non-competition clause. The author is restricted from competing with his own work – the book the publisher now controls. And the publisher controls the book with a very broad grant of rights these days.

Here’s the language:

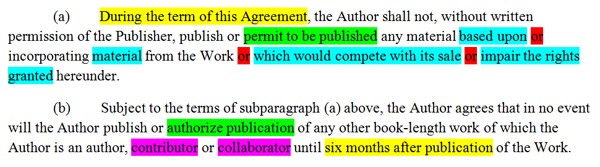

Conflicting Publications

(a) During the term of this Agreement, the Author shall not, without written permission of the Publisher, publish or permit to be published any material based upon or incorporating material from the Work or which would compete with its sale or impair the rights granted hereunder.

(b) Subject to the terms of subparagraph (a) above, the Author agrees that in no event will the Author publish or authorize publication of any other book-length work of which the Author is an author, contributor or collaborator until six months after publication of the Work.

What do we see?

Let’s touch on a subtle point first. A normal non-lawyer reader would be a little confused by the first paragraph and assume the second paragraph was explanatory. Yes, the second paragraph explains a bit about the first paragraph, but it doesn’t limit the first paragraph.

In fact, the second paragraph is specifically made “subject to the terms” of the first. Theoretically, if there were a conflict between the two paragraphs, the first would govern.

Why is this a subtle point? Someone reading through the contract quickly would likely retain the mental impression that the Conflicting Publications clause said he/she couldn’t write another book until six months after the publication of the first one. If that was fine, a mental checkmark would be placed next to the clause saying, “OK” or something like that.

In fact, the first paragraph is much broader than the second.

PG recognizes this tactic because he did this sort of thing regularly when he was drafting contracts and wanted to slide something past opposing counsel if opposing counsel was a jerk. Obscure one sub-paragraph and place it next to a clearly-stated sub-paragraph so the clear subparagraph effectively overwrites the less-clear one in the reader’s mind.

PG is sure there must be a psychological term that describes this mental overwriting. The legal term for it is “Hardball.”

PG was about to digress on when he feels hardball is justified in contract negotiations, but that’s for another post. For the present post, an author and (in PG’s ever-so-humble opinion) most agents are not equipped to counter hardball tactics by publishers.

Let’s dig in.

First, we’ll do some color-coding to show how PG’s deranged legal mind sees the clause.

Time

Let’s look at the time provisions – marked in yellow.

During the term of this Agreement. In a typical publishing contract currently offered, the author is giving the publisher rights to the book for the life of the copyright. This means the life of the author plus 70 years in the U.S.

This is an exceedingly long period for a non-competition clause. It’s very common for high-tech, biotech and pharmaceutical companies to have their employees sign non-competition agreements. These never last for more than three years after the employee leaves the company for any reason. In California, absent the sale of a business by an owner or part-owner, non-comp agreements are not enforceable for any length of time.

Additionally, in the real world, the scope of the non-competition agreement is often limited to those companies that directly compete with the employer. Depending upon the nature of the employer, a non-comp agreement will often cover only a limited geographic area.

These limitations apply regardless of how valuable the employee is. The head software programmer for the iPad is not restricted from quitting and going to work for a competitor under California law. The employee may be prevented from sharing Apple trade secrets, but he/she is free to go to work for Microsoft.

Since an author is not an employee of the publisher, the laws relating to employee non-competition agreements may not apply. However, the public policy behind those laws – you can’t interfere with someone’s right to earn a living in his/her chosen field – do apply as far as PG is concerned.

The time provision in the second paragraph restricts the author from publishing any book until six months after publication of the Work. (The “Work” is the book under contract.)

Who controls when the Work is published? The publisher. How long will it be until the Work is published? Probably about 18 months from signing the contract, although it can be longer. The timing is up to the publisher.

What does this mean?

Since the author is not permitted to authorize publication of another book, this means the author will be living on whatever portion of the advance is paid before publication (often 50% these days). For how long? Until six months following publication.

PG thinks a reasonable interpretation of authorize publication would prevent the author from signing a publishing contract and receiving an advance for an entirely unrelated book until six months after publication of the first.

So, even if you’re writing up a storm, either make that advance last or go back to being a barista until you’re free to sell another book.

Scope of Non-Compete

Let’s look at the blue portions in the first paragraph.

The author can’t create or permit to be created (more on this later) any material based upon or incorporating material from the Work or which would compete with its sale or impair the rights granted hereunder.

What’s any material? What’s based upon?

If the author writes a fantasy novel with an original fantasy creature – we’ll call it a Cypriot Boomslang – the author probably can’t have t-shirts printed for friends and family with an original drawing of a Cypriot Boomslang on them because the shirts would be based upon material in the book.

In fact, the Cypriot Boomslang won’t make an appearance in anything the author does for anyone else except this publisher for the rest of the author’s life.

Material is not a defined term, so it can cover lots and lots of ground.

But Wait! There’s More!

Look at the little red or’s in the first paragraph. The way Passive Guy’s legal mind reads that paragraph is:

- During the term of this Agreement [forever], the Author shall not, without written permission of the Publisher [never get it without paying money], publish or permit to be published any material based upon the Work.

- During the term of this Agreement [forever], the Author shall not, without written permission of the Publisher [never get it without paying money], publish or permit to be published any material incorporating material from the Work.

- During the term of this Agreement [forever], the Author shall not, without written permission of the Publisher [never get it without paying money], publish or permit to be published any material which would compete with its [the book’s] sale [in any form].

- During the term of this Agreement [forever], the Author shall not, without written permission of the Publisher [never get it without paying money], publish or permit to be published any material which would impair the rights granted hereunder.

Items 1 and 2 bring up the undefined material again. The author can’t publish any material. The paragraph doesn’t say book or story, although they would almost certainly be material. How many different things does material cover? Perhaps this is left to the imagination of the publisher and its attorneys.

Items 3 and 4 are even more interesting.

Item 3 says the author can’t create anything that competes with the sale of the book or anything derived from the book that is the subject of the contract.

What competes with the sale of a romance novel? Every other romance novel? What competes with the saleof a romance novel written by Big Bubba John? Every other romance novel Big Bubba John ever writes.

With one contract and one advance for one romance, Big Bubba John might be out of the romance business for good if the publisher wants to enforce the contract. He’ll be stuck writing about monster truck races for the rest of his career.

Item 4 says the author can’t create things that impair the rights granted hereunder.

Impair. That’s a lovely word, never defined in the contract. Impair could be construed to cover lots and lots of different acts by the author without much imagination.

The rights granted hereunder. What rights are those? Well, traditional subsidiary rights for one thing – movies, plays, comic books, t-shirts, action figures, etc. So you can’t impair any of those rights with anything you ever write or allow anyone else to write.

But there are far more rights than just traditional subsidiary rights. After getting burned by publishing contracts that don’t mention ebooks, publishers changed standard publishing contracts so the author grants rights to future technology of any type that might incorporate anything from the book. Is that clear? You signed the contract, so don’t you go out and impair any of that stuff or you’ll violate that contract.

Permit or Authorize

The two provisions marked in green extend the author’s obligations to acts of third parties. PG doesn’t like either one, but the first paragraph bothers him the most. The author agrees not to permit to be published anything the Publisher might object to thirty years or fifty years in the future.

Does this place an affirmative obligation on the author to police his/her copyrights to prevent loss orimpairment of the publisher’s rights? If the author knows of such damaging acts by third parties, is the author permitting those acts if the author stands by and does nothing?

Contributor or Collaborator

Finally we reach the purple text that applies during the publication-plus-six-months time period.

Neither contributor nor collaborator is defined in the contract.

Let’s go back to that closet romantic, Big Bubba John. What if his wife, Little Bubba Sue, is inspired by her husband’s lyrical prose and decides she wants to write a romance novel as well?

As is typical with husband/wife authors, Little Bubba Sue hands Big Bubba John a stack of paper hot off the printer and says, “What do you think about what I’ve written today? Too many vampires or too few?”

Big Bubba John sits down with a red pencil and dutifully goes through the manuscript making big red X’s, writing in new dialogue and correcting numerous grammatical errors. (Little Bubba Sue went to welding school instead of Yale and is a little wobbly on grammar.)

Is Big Bubba John contributing to his wife’s romance novel? Is he collaborating with her? PG says Yea.

Attorneys who have read this far will say something about privileged communications between husband and wife and they would be correct until Little Bubba Sue blogs about what a wonderful help her big ugly husband was with her vampire romance and dedicates her book to him to show her gratitude for all his editing and suggestions.

What’s the bottom line on this clause?

It is ridiculously easy for the author to inadvertently breach the publishing contract under this clause. Want to sue your publisher for stealing ebook royalties from you? A clause like this would be Hammer No. 1 in the hands of the publisher’s counsel in any litigation between author and publisher. You might win on ebook royalties, but you would lose on something under your non-competition clause.

What are you going to do if you see this contract provision in something you’re supposed to sign?

When you receive a contract with a clause like this in it, you swallow hard, then bravely raise all the issues PG discussed. Your editor, Jane, will say something like, “We hear this rubbish all the time. Passive Guy was cutting his pills in half when he wrote that blog post. This isn’t anything like what we mean by this provision. What this clause really means is XYZ.”

You reply in your sweetest voice, “Oh, Jane, I’m so pleased to hear that. I knew I had the best publisher in the world. So there is no confusion in the future when I’m not dealing with someone as understanding as you are, let’s put XYZ in the contract.”

Why do this if Jane says the contract means XYZ? Doesn’t that solve the problem?

It does solve the problem if:

- Jane outlives you by 70 years.

- Jane is still working at the same publisher during that entire time.

- Jane doesn’t ever have a boss who says, “This company enforces its contracts according to their terms,” or “Das Unternehmen setzt seine Verträge entsprechend den jeweiligen Bedingungen.” (Shout out to all of PG’s fans at Bertelsmann)

In the reality-based world, business contracts last three years, five years, ten years. You might risk your career on Jane’s assurances during those time periods. You don’t want that risk for the rest of your life.

Get it in writing and make sure the writing matches what your agreement really is. Assurances feel wonderful, but solid contracts pay better.

One last lesson in contract analysis before we close our happy discussion.

You might say to yourself, “Well, when the book goes out of print, I’ll get my rights back.”

Maybe.

Depends upon how your Out of Print clause reads.

If your OOP clause ends with “Publisher shall have no further rights to publish the Work,” that clause may not eliminate the publisher’s other rights under the Conflicting Publications paragraphs.

You want your OOP clause to end with something like, “Neither Publisher nor Author shall have any further rights or obligations under this Agreement and this Agreement shall thereafter be null and void.”

Speaking of Out of Print clauses, Passive Guy hasn’t seen any good ones lately, so he will end with a request for more contributions to his Contract Collection.

Here’s a link to the 33 comments to the original post. Feel free to comment here if you like.

Mental note. If ever get a contract like this, point out that I would not wish to do anything that caused the book I make money on… to make less money. Therefore, this is a stupid clause, put in only to enable the publisher to tick me off and go neener neener. If the publisher has no intention of going neener neener at me, then the clause is pointless and should be drop-kicked.

Or… Just say “No” to Restraint of Trade.

When I was practicing law, I dealt with non-compete clauses. The scope varies from state to state in the United States. If not defined in the contract, depending on the judge, the scope would be construed to either 1) follow the law of the state in which the contract was executed or 2) follow the law of the state in which jurisdiction of the lawsuit lies (if there is no suit, it does not matter).

In some states, non-competes are limited by law to a term of years (usually 3 after an employee leaves the company).

You know, I just realized that all the non-competes I did involved ex-employees. I have no experience with author-publisher non-competes. I would have to read some case law on the subject. Something tells me there ain’t much case law out there. Kinda like trying to find a case in which Microsoft was a litigant — they move to seal all records. I bet publishers do the same.

Antares – I haven’t heard of any litigation attacking these types of clauses by authors.

One question in litigation is whether one of the key elements limiting employee non-compete agreements – as a public policy, we don’t want broad prohibitions that will prevent people from earning a living – will apply to author/publisher contracts where the author is not an employee.

Does the phrase ‘restraint of trade’ sound familiar?

I’m not a lawyer. I couldn’t even play a lawyer on TV, makeup and expensive suit or no.

But the first paragraph would have had my back up immediately, let alone the second. PG’s analysis (linked to above) goes into the legal-world meanings of things, but the plain English is bad enough. All those absolutes and forevers would be worrisome without knowing what Blackstone had to say about the language.

It all goes to tell me that the editor who refused my manuscript did me a favor. Next time I go to a con I’ll offer to buy her a drink.

Regards,

Ric

Awesome post! Very educational.

I ask again: why would anyone want to deal with a traditional publisher? It seems to me that these guys are doing their best to work themselves out of a job.