From The Wall Street Journal

The web is in crisis, and artificial intelligence is to blame.

For decades, seeking knowledge online has meant googling it and clicking on the links the search engine offered up. Search has so dominated our information-seeking behaviors that few of us ever think to question it anymore.

But AI is changing all of that, and fast. A new generation of AI-powered “answer engines” could make finding information easier, by simply giving us the answers to our questions rather than forcing us to wade through pages of links. Meanwhile, the web is filling up with AI-generated content of dubious quality. It’s polluting search results, and making traditional search less useful.

The implications of this shift could be big. Seeking information using a search engine could be almost completely replaced by this new generation of large language model-powered systems, says Ethan Mollick, an associate professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania who has lately made a name for himself as an analyst of these AIs.

This could be good for consumers, but it could also completely upend the delicate balance of publishers, tech giants and advertisers on which the internet as we know it has long depended.

AI agents help cut through the clutter, but research is already suggesting they also eliminate any need for people to click through to the websites they rely on to produce their answers, says Mollick. Without traffic, the business model for many publishers—of providing useful, human-generated information on the web—could collapse.

Over the past week, I’ve been playing with a new, free, AI-powered search engine-slash-web browser on the iPhone, called Arc Search. When I type in a search query, it first identifies the best half-dozen websites with information on that topic, then uses AI to “read” and summarize them.

It’s like having an assistant who can instantly and concisely relate the results of a Google search to you. It’s such a timesaver that I’m betting that once most people try it, they’ll never be able to imagine going back to the old way of browsing the web.

While Arc Search is convenient, I feel a little guilty using it, because instead of clicking through to the websites it summarizes, I’m often satisfied with the answer it offers up. The maker of Arc is getting something for free—my attention, and I’m getting the information I want. But the people who created that information get nothing. The company behind Arc did not respond to requests for comment on what their browser might mean for the future of the web. The company’s chief executive has said in the past that he thinks their product may transform it, but he’s not sure how.

In December, the New York Times sued Microsoft and OpenAI for alleged copyright infringement over these exact issues. The Times alleges that the technology companies exploited its content without permission to create their artificial-intelligence products. In its complaint, the Times says these AI tools divert traffic that would otherwise go to the Times’ web properties, depriving the company of advertising, licensing and subscription revenue.

OpenAI has said it is committed to working with content creators to ensure they benefit from AI technology and new revenue models. Already, publishers are in negotiations with OpenAI to license content for use in its large language models. Among the publishers is Dow Jones, parent company of The Wall Street Journal.

Activity on coding answer site Stack Overflow has dropped in the face of competition from these AI agents. The company disclosed in August that its traffic dropped 14% in April, the month after the launch of OpenAI’s GPT-4, which can be used to write code that developers otherwise would look up on sites like Stack Overflow. In October, the company announced it was laying off 28% of its workforce.

“Stack Overflow’s traffic, along with traffic to many other sites, has been impacted by the surge of interest in GenAI tools over the last year especially as it relates to simple questions,” says Matt Trocchio, director of communications for the company. But, he adds, those large language models have to get their data from somewhere—and that somewhere is places like Stack Overflow. And the company has responded to this fresh wave of competition by releasing its own AI-powered coding assistant, OverflowAI.

Traffic to sites like Reddit, which is full of answers from real people, could be next, says Mollick. A spokesman for Reddit said that the one thing a large language model can never replace is Reddit’s “genuine community and human connection,” and that its “community-first model imparts trust because it’s real people sharing and conversing around passions and lived experiences.” Reddit is set to go public in March.

Liz Reid, general manager of search at Google, has said that the company doesn’t anticipate that people will suddenly switch over to AI chat-based search all at once. Still, it’s clear that Google is taking the threat of AI-powered search very seriously. The company has gone into overdrive on this front, reallocating people and resources to address the threat and opportunity of AI, and is now rolling out new AI-powered products at a rapid clip.

Those products include Google’s “search generative experience,” which pairs an AI-created summary with traditional search results. “Users are not only looking for AI summaries or AI answers, they really care about the richness and the diversity that exists on the web,” Google CEO Sundar Pichai said in a recent CNBC interview. “They want to explore too. Our approach really prioritizes that balance, and the data we see shows that people value that experience.”

This moment also means there is opportunity for challengers. For the first time in years, scrappy startups can credibly claim that they could challenge Google in search, where the company has above a 90% market share in the U.S.

Eric Olson is CEO of Consensus, a search startup that uses large language models to offer up detailed summaries of research papers, and to offer insights about the scientific consensus on various topics. He believes that AI-powered search startups like his can offer an experience superior to Google’s on specific topics, in a way that will carve off chunks of Google’s search business one piece at a time.

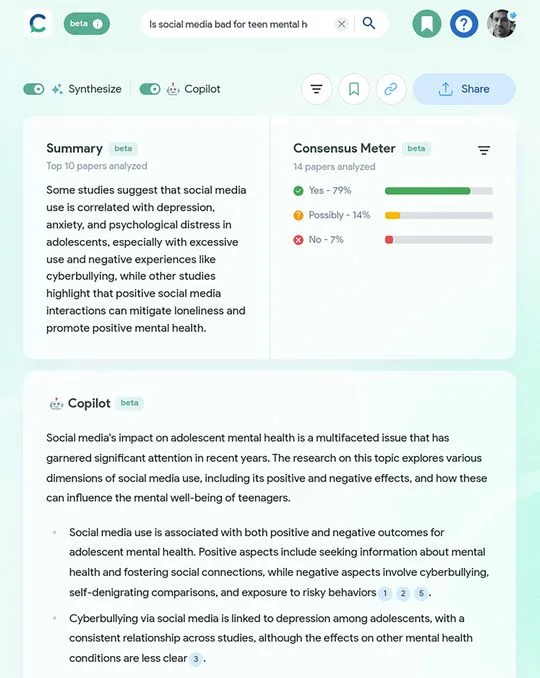

Asking Consensus whether social media is bad for teen mental health provides an instructive example: Consensus uses AI to summarize the top 10 papers on the subject, and then offers a longer breakdown of the diversity of findings on the issue, in which every paper cited is individually summarized.

It’s an impressive feat, one that would take a non-expert human many hours of effort to accomplish on their own. (I’ll save you even more time. The short answer is yes.)

This kind of AI-powered search is also better than simply asking the same question of a large language model like ChatGPT, which is famously lax when it comes to answering such questions, often making up studies that don’t exist, or misattributing information. This is known as the “hallucination” problem, and forcing an AI to draw only from a prescribed set of inputs—like scientific papers—can help solve it, says Olson.

This doesn’t mean that the problem of hallucination can be eradicated completely, says Mollick. This could put Google at a disadvantage, because if the world’s largest search engine gets one out of 10 queries to its AI wrong, that’s a problem, but if a startup with an experimental offering has the same performance, it can look like a triumph.

. . . .

Despite these issues, users may move toward AI-based answer engines for the simple reason that AI-generated content threatens to make the web, and existing search, less and less usable. AI is already being used to write fake reviews, synthesize fake videos of politicians, and write completely made-up news articles—all in hopes of snatching dollars, votes and eyeballs on the cheap.

“The recent surge in low-quality AI-generated content poses significant challenges for Google’s search quality, with spammers leveraging generative AI tools, like ChatGPT, to produce content that — usually temporarily — ranks well in Google Search,” search-engine optimization expert Lily Ray told me.

The problem isn’t just with Google’s search results. AI-generated content has also been spotted in listings within Google Maps, the summaries that appear above and alongside search results known as “featured snippets,” within Google’s shopping listings, and in the news items the company features in its “top stories,” news and “discover” features, she adds.

It’s important to note that Google has for decades battled those who would manipulate its search algorithms, and it continually updates its systems to sweep away spammy content, whatever the source. Its guidelines on AI-generated content, last updated in February, re-iterate that the company is fine with using AI to help generate content—but only if it serves the people consuming it.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (Sorry if you encounter a paywall)

OK, nobody has said it yet:

It’s the end of the web as we know it

And I feel fine

because I’m heavily medicated after suffering yet more back spasms. And because twenty years ago this month, this undermined any confidence I had in internet service providers.

That said, thus far the “age of bots replacing search” has resembled “things can’t get any worse, can they?”

Personally, I’ll skip autogenerated commentary. I still just want the sources, thanks.

The more advanced LLM search engines build their answers from multiple sources and multiple models and then (as in classic SF) weigh the answers against each other. When the model developers talk about imposing “guard rails” on their bots, they are talking about giving them “common sense” boundaries.

They will never be 100.000000% trustworthy, but then neither is the internet they are working off. Neither is an all-knowing oracle. The best you can hope is signposts to *somebody’s* narrative. Then you pick your poison.

Remember that Google search constantly tweaks their algorithms to game the presentation order of the search links. The ultimate guard rail for both Search engines and AI is the end user.

When it comes to facts, what matters if if they are true, not if 97% of ‘the right’ people say it’s true.

When science or engineering get revolutionized, it’s because someone disagrees with ‘what everybody knows’ and is stubborn enough to stick to it.

Anything that distills things down to a single answer is a bad idea.

True.

*If* it pretends to be the one and only answer.

(Like corporate media.)

For all the handwringing, that is not what the LLM search engines do.

Bing Co-pilot, for one, offers citations and links in its answer so the user can go to the sources and judge by themselves. No different from the “web as we know it”. Except it skips paid placement links. (For now.)

Only the lazy and gullible treat LLM search as an Oracle, especially when there is so much concern over “hallucination”.

But then, big corporate media (WSJ included) assumes every user is lazy and gullible, not totally without evidence; it’s what keeps *them* in business. For now. Their endless LLM carping shows their insecurity and fear that those same lazy and gullible masses will shift their blind trust from them to the new “font of facts”. Again, not totally without evidence.

“only the lazy and gullible” describes a lot of people, and “The Science(tm)” frequently claims that there is only one answer to a lot of things as well

LLMs are pretty good for predicting what’s likely to come next, but not good at keeping track of how they ‘know’ that.

Using them as a language parser to understand what someone is searching for is a good thing, using them as if their output was the result of a search engine is something else.

There have been two many cases where people who’s job is to know better (lawyers for example) have ignored the possibility of ‘hallucination’ and not even checked the items cited by the LLM before relying on them.

Sure.

Lazy and gullible are all over.

Fools, too.

Which is my point.

You can’t idiot proof anything because idiots are infinitely ingenious.

See the Darwin Awards:

https://darwinawards.com/darwin/

If we fret about the ways everything can be misused nothing would get done. The best anybody can do is aim products at the minority with common sense and hope the lazy and gullible don’t take anybody with them as they remove themselves from the gene pool.

“Think of it as evolution in action.’

You raise some good points, L.

I was an early adaptor of the Internet once it escaped from academia.

False information showed up all too quickly and I learned that the source was often more important than the information. And even generally reliable sources could occasionally be fooled into disseminating bad information.

Human nature persists in the electronic world.

I think one of the biggest problems with this kind of search is actually that I don’t trust it to know whether the info is correct or to know whether it’s deductions are correct. I can generally figure out from a human generated article or authoritative source if it’s likely to be correct, though tbf, even academics just make stuff up sometimes. But why would a machine ne able to accurately assess human duplicity delivered confidently. There a ton of factors, not even all in the text, that help us decide whether we trust a website.