From The Wall Street Journal:

What a cursed kind of privilege it is to be the physician in charge of the life of a world leader. In April 2020, stories circulated about doctors from the intensive-care unit of London’s St. Thomas’s Hospital texting the Downing Street communications team when Covid-suffering Boris Johnson, as the prime minister himself would later put it, “could have gone either way.” If the virus took a lethal turn, his doctors and PR flacks wondered, who would say what, when? Scenes from the film “The Death of Stalin” flashed by: the body, the indecision, the panic.

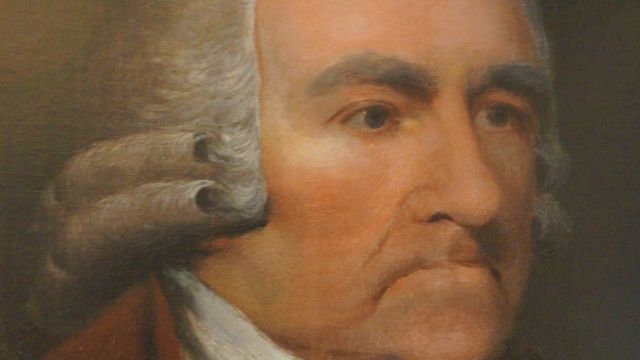

How much worse it must have been for the 56-year-old Thomas Dimsdale, in his dark suit and curled wig, drawn from the comfort of his farmhouse in Hertfordshire, England, to travel a grueling 1,700 miles overland in a carriage to St. Petersburg. Dimsdale had been summoned by Catherine the Great to inoculate not only the empress herself but also her 13-year-old heir, the Grand Duke Paul. Catherine sought protection from smallpox, that scourge of the world that, through the ingenuity of science and social persuasion, became the first—and still the only—disease to have been eradicated by the interventions of mankind.

The smallpox pandemic makes Covid seem like a scene-stealing extra: More lethal and more contagious, it rolled through society in wave after devastating wave. In London in 1752, it was responsible for one out of every seven deaths. Uncertainty followed fever and pustules. The remedy in itself was ineffective and miserable: bleeding, puncturing to release the pus, and sweating in blankets. It was a course of treatment determined by a lingering belief in the four vital humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, yellow bile—whose balance supposedly dictated health. (One of Dimsdale’s contributions to the march of medical history seems to have been his insistence on opening the window.)

As Lucy Ward dramatically relates in “The Empress and the English Doctor: How Catherine the Great Defied a Deadly Virus,” Catherine’s invitation was a high-stakes affair, a testament to Dimsdale’s writings on the methodology of smallpox inoculation and his reputation for solicitous care. His Quaker upbringing had encouraged a brand of outcome- rather than ego-led practice.

Inoculation preceded vaccination. The approach was initially brought to Europe by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who had first noted the practice in Constantinople. She insisted on having her own children inoculated, and convinced the Hanoverian court to follow suit, led by the future Queen Caroline, whose children, too, were subjected to the procedure.

The disease followed a heartbreaking trajectory, killing children and the young, disfiguring women and destroying their prospects for marriage even if they survived. An incredible “five reigning monarchs were dethroned by smallpox in the eighteenth century,” we are told, including Peter the Great’s grandson, the child Emperor Peter II. In Vienna, Empress Maria Theresa lost her son, two daughters and two daughters-in-law. Survival rates in Russia were particularly low. No wonder Catherine wanted to try her luck with science.

As devastating as smallpox was, for the empress herself and the grand duke who would succeed her to personally undergo inoculation was a risk to both patient and doctor. On the success side stood immunity from the disease, an almost holy example for Catherine’s people, and as-yet-untold riches for her nervous doctor. On the other side, not only the fact that all Russia would refuse the treatment if their “Little Mother” died, but also a disaster for Dimsdale and the son who had accompanied him. Geopolitics came into play too—if things went wrong, some would interpret it as a foreign assassination.

All the descriptions of lancet cuts and pus are one thing—it is the experimentation on impoverished children that makes for painful reading. Young army cadets are experimented on; a 6-year-old, “small as a bug,” according to Catherine, supplies the viral matter to his empress, who is prepared with “five grains of the mercurial powder” and purged with “calomel, crabs’ claws and antimony.” Then she waits it out at Tsarskoe Selo, her summer palace, in the hope of a desirable progression: outbreak, recovery.

With a happy result for her and her less-robust son, Catherine sets about publicizing the success. Dimsdale receives the equivalent of more than $20 million and a barony.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)

A brief summary of the history of Catherine the Great, whose life was substantially extended by Dr. Dimsdale:

- She was born in Prussia as Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg.

- Prussian king Frederick the Great took an active part in promoting the future Catherine (then Princess Sophie) as an ideal spouse for a likely future tsar of Russia.

- Sophie arrived in Russia in 1744 and aggressively worked to ingratiate herself with the reigning ruler, Empress Elizabeth and with the Russian people. She learned to speak, read and write Russian, rising at night and walking about her bedroom barefoot, repeating her lessons. When she wrote her memoirs, she said she made the decision then to do whatever was necessary and to profess to believe whatever was required of her to become qualified to wear the crown.

- She became a member of the Russian Orthodox Church and received a new name, Catherine (Yekaterina or Ekaterina)

- The following day, she married the man who would become Peter III. Catherine was 16 at the time.

- Peter was an eccentric idiot when she married him and after he ascended to the Russian throne.

- Upon the death of his mother, Peter ascended to the throne.

- Catherine organized a coup to overthrow her husband. Six months after Peter became tsar, Catherine had Peter arrested and he signed a written abdication of the throne in favor of his wife.

- Shortly thereafter, Peter died. There were rumors that he had been assassinated, but after an autopsy, the official cause of death was found to be a severe attack of haemorrhoidal colic and an apoplexy stroke.

- Catherine ascended to the throne. Her crown weighed over five pounds and contained 75 pearls and 4,936 Indian diamonds forming laurel and oak leaves, the symbols of power and strength, and was surmounted by a 398.62-carat ruby spinel that previously belonged to the Empress Elizabeth, and a diamond cross. A photo of the crown and orb taken in 1896 is inserted at the bottom of this post.

- Catherine reigned as monarch for well over thirty years, from 1762–1796.

- During her reign, Catherine extended by some 520,000 square kilometres (200,000 sq mi – an area a little smaller the State of Texas and about the size of present-day France ) the borders of the Russian Empire, absorbing New Russia, Crimea, Northern Caucasus, Right-bank Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Courland at the expense, mainly, of two powers—the Ottoman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.