From The Paris Review:

On March 4, 1960, the French freighter La Coubre, delivering Belgian arms to Havana Harbor, exploded, killing 101 people. Fidel Castro immediately denounced the United States for “sabotage.” To protest the “heinous act,” commanders Che Guevara, Ramiro Valdés, Camilo Cienfuegos, William Morgan, Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo, Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado (who would remain the president of Cuba until 1976), and Fidel Castro walked arm in arm down Calle Neptuno, forming a dramatic contrast between the street’s garish neon signs and the plain green of their uniforms—and the sobriety of their mission.

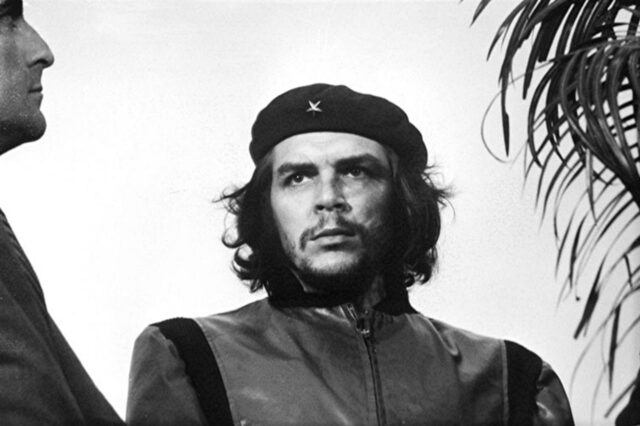

In a photo taken on March 5, 1960, by Alberto Korda at a ceremony for the victims of the tragedy, Che appears full of sorrow, anger, and determination. That image would become ubiquitous across the world, a trademark, appearing on T-shirts and countless other commodities. Che transcended his personhood and became a symbol for both the struggle against tyranny and of tyranny itself. His spirit seemed to impress even nihilist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, who, with Simone de Beauvoir, was there that mournful day when Che’s picture was taken.

One of Che’s first questions in taking over as president of the Banco Nacional de Cuba in November was where Cuba had deposited its gold reserves and dollars. When he was told Fort Knox, he said that the gold would have to be sold and converted into currency in Canadian and Swiss accounts. During a speaking engagement at the bank two months later, Che apologized “because my talk has been much more fiery than you would expect for the post I occupy; I ask once more for forgiveness, but I am still much more of a guerrilla than President of the National Bank.” As if to prove it, he signed banknotes with his nom de guerre: “Che.” The agenda was the struggle, and so it would remain, and La Coubre only confirmed the necessity of his resolve and commitment to the bitter end.

Most every Thursday evening that season, U.S. Ambassador Philip Bonsal dined with Ernest Hemingway. One evening he came also to deliver an upsetting message: the U.S. government was going to break off relations with Cuba. Washington decreed that Hemingway, as the island’s most conspicuous, high-profile expatriate, should leave Cuba as soon as possible and publicly proclaim his disapproval of Castro’s government. If he did not, he could be sure that he would face serious and unpleasant consequences. Hemingway protested: his business was not politics but writing, and for twenty-two years Cuba had been his home. Be that as it may, Bonsal replied that high officials maintained a different view, had used the word traitor, and saw his collaboration as a nonnegotiable.

That was the message he had to deliver, the ambassador said, and he believed that Ernest should take it quite seriously. As the course of dinner conversation drifted to other subjects, the Hemingways and their dinner guests tried to think about happier things but found it difficult to forget what had just been said. Hemingway was not one to take orders, and one can imagine that this news and the imminent loss of his cherished home in Cuba would have been very unsettling. From Bonsal’s warning, it is also difficult to know the severity of the “consequences” that might have come as a response to Hemingway’s acts of “treason.” A letter of reprimand, loss of citizenship, a fine, imprisonment, or something much more sinister?

Link to the rest at The Paris Review

“Che transcended his personhood and became a symbol for both the struggle against tyranny and of tyranny itself.”

And all this time I thought Che was the symbol of tyranny.

Foolish me.

Dan