From The Paris Review:

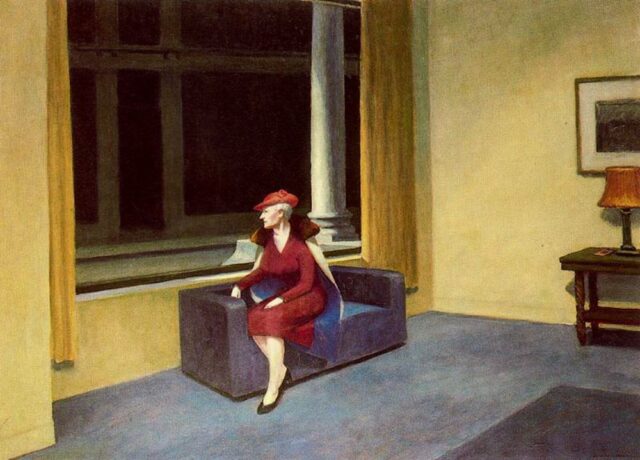

I am puzzled by the mournfulness of cities. I suppose I mean American cities mostly—dense and vertical and relatively sudden. All piled up in fullest possible distinction from surroundings, from our flat and grassy origins, the migratory blur from which the self, itself, would seem to have emerged into the emptiness, the kindergarten-landscape gap between the earth and sky. I’m puzzled, especially, by what seems to me the ease of it, the automatic, fundamental, even corny quality of mournfulness in cities, so built into us, so preadapted for somehow, that even camped out there on the savannah, long before we dreamed of cities, I imagine we should probably have had a premonition, dreamed the sound of lonely saxophones on fire escapes. What’s mourned is hard to say. Not that the mourner needs to know. It seems so basic. One refers to certain Edward Hopper paintings—people gazing out of windows right at sunset or late at night. They’ve no idea. I don’t suppose that sort of gaze is even possible except within the city. You can hear the lonely saxophone-on-fire-escape (in principle, the instrument may vary) cry through Gershwin. Aaron Copland. You remember Sonny Rollins on the bridge (the structure varies, too, of course). So what in the world is that about? That there should be a characteristic thread of melody, a certain sort of mood to sound its way through all that lofty, sooty jumble to convey so clear and, as it seems, eternal a sense of loss and resignation. How in the world do you get “eternal” out of “saxophone” and “fire escape”? It doesn’t make much sense. That it should get to you—to me at least—more sharply, deeply, sadly than the ancient, naturally mournful, not to say eternal, sound of breath through reed or bamboo flute.

Not too many years ago, as I began to wonder about the mournfulness of cities—its expression in this way—I brought a recording of Aaron Copland’s Quiet City concert piece to my then-girlfriend Nancy’s house on a chilly winter evening. She had friends or family staying, so we slept in the front bedroom, which, because of its exposure or some problem with the heater, was quite cold. So I remember all the quilts and blankets and huddling up together as if desperate in some Lower East Side tenement and listening to this music break our hearts about ourselves, our struggling immigrant immersion and confusion in this terrible complexity. The lonely verticality of life. And why should sadness sound so sweet? I guess the sweetness is the resignation part.

I’d like to set up an experiment to chart the sadness—try to find out where it comes from, where it goes—to trace it, in that melody (whichever variation) as it threads across Manhattan from the Lower East Side straight across the river, more or less west, into the suburbs of New Jersey and whatever lies beyond. This would require, I’m guessing, maybe a hundred saxophonists stationed along the route on tops of buildings, water towers, farther out on people’s porches (with permission), empty parking lots, at intervals determined by the limits of their mutual audibility under variable conditions in the middle of the night, so each would strain a bit to pick it up and pass it on in step until they’re going all at once and all strung out along this fraying thread of melody for hours, with relievers in reserve. There’s bound to be some drifting in and out of phase, attenuation of the tempo, of the sadness for that matter, of the waveform, what I think of as the waveform of the whole thing as it comes across the river losing amplitude and sharpness, rounding, flattening, and diffusing into neighborhoods where maybe it just sort of washes over people staying up to hear it or, awakened, wondering what is that out there so faint and faintly echoed, faintly sad but not so sad that you can’t close your eyes again and drift right back to sleep.

It isn’t possible to hear it all at once. You have to track the propagation. All those saxophones receiving and repeating and coordinating, maybe, for an interval or two before the melody escapes itself to separate into these brief, discrete, coherent moments out of sync with one another, coming and going, reconnecting, fading out and in again along the line in ways that someone from an upper-story window at a distance might be able to appreciate, able to pick up, who knows, ten or twenty instruments way out there faintly gathering, shifting in and out of phase along a one- or two-mile stretch. And I imagine it would be all up and down like that—that long, sad train of thought disintegrating, recomposing here and there all night in waves and waves of waves until the players, one by one, begin to give it up toward dawn like crickets gradually flickering out.

In order to chart the whole thing as intended, though, we will need a car, someone to drive it slowly along the route with the windows down while someone else—me, I suppose—deflects a pen along some sort of moving scroll, perhaps a foot wide and a hundred feet long, that has been prepared with a single complex line of reference along the top, a kind of open silhouette, a structural cross section through the route, with key points noted, from the seismic verticalities of Manhattan through the quieter inflections of New Jersey and those ancient tract-house neighborhoods and finally going flat (as I imagine, having no idea what’s out there) into what? Savannah, maybe? Or some open field with the final saxophonist all alone out there in the grass.

Link to the rest at The Paris Review

PG’s in a distinctly contrary mood today. The title of the OP, The Mournfulness of Cities (which the first line narrowed to American cities) suggests sadness is embedded in their general character.

Then, the rest of the OP talks about New York City and New Jersey.

You got cold one night in Manhattan? Try Minneapolis in January!

Minnesota dogs stick to the sidewalks in January.

People plug in their gasoline-powered cars so electric engine block heaters will help to make sure their engines aren’t a solid block of frozen metal in the morning.

Minneapolis people go to Manhattan in January to warm up.

(I’m not forgetting you in January, Winnipeg. I know you go to Minneapolis to work on your tans when the Minneapolis people are all in Manhattan and hotel rooms are really cheap.)

Setting aside the weather, what about all of the other cities – Chicago, Denver, San Diego? All the same as Manhattan?

Au contraire tu es fou!!

PG has spent a lot of time in New York City, lived in Chicago, and spent lots and lots of time in many other large American cities.

He has to work hard to identify a city that is truly mournful. The only one that comes immediately to mind is Gary, Indiana. PG hasn’t been back to Gary for a long time, but it was pretty mournful when he last passed through.

You can certainly be downcast anywhere, including New York City, but PG’s memories of Manhattan (he’ll not speak to the Bronx) are filled with how much energy he picked up walking down the streets at all hours of the day and night.

He named Chicago (terrific city!), Denver and San Diego, but could have named dozens more that have an upbeat, unique vibe that isn’t really replicated anywhere else.

Outside the United States, he loves London and Paris. Oxford feels like he was born in one of the colleges. If heaven looks anything like Florence, PG can’t wait to get there. No mournfulness in Florence for PG.

Contrary and upbeat! That’s PG for the next ten minutes, maybe more!

Well, at least it introduced me to a Copland piece I hadn’t heard…

We lived in Manhattan on the Lower East Side in the 70s in post-student poverty amid a good bit of criminal riff-raff, but what I remember best were not the crowds and funk nor the grime and noise but the unusual days: hiking from Mid-town to Wall Street on a work day with financial documents to deliver after a blizzard shutdown when many of the (few) other people visible were trying out their cross-country skis; or baby-sitting an early-mainframe-computer database build very late at night alone (apparently) in a high-rise Mid-town office building listening to the radio’s first alarmed announcements out of Sweden about the Chernobyl event, followed immediately by the usual daily topical jokes out of Wall Street at 5 AM when the traders start their day (“What walks a little funny and glows in the dark? Chernobyl Chicken”).

C’mon, everyone here knows perception of any given thing at any given time is more fluid than a cat faced with an empty space. Searcy was just feeling mournful and maybe a bit poetic, and he allowed the melodic phrase “the mournfulness of cities” to turn his head. I seldom enjoy “elevated”-sounding writing, but I have to admit “the sound of lonely saxophones on fire escapes” has enough of a Raymond Chandler quality to pull me into the same feeling.

Indeed, it sounds like a good mood for writing Noir.

Not so good for surviving a pandemic, though. 😉

I would have loved to take the OP’s author back to Berlin in 1988, on the west side of The Wall, and make him show me something mournful. (Oh, it’s in another language, and that makes it mournful? Typical New Yorker.) I wouldn’t even have to go down to the Kurfurstendamm after dark to overcome anything that was mournful on the western side…

I’ll freely admit that Bonn was professionally mournful. By design. You would have been, too, if your less-than-a-century-old nation had been ripped in half and you’d been elevated from a sleepy backwater provincial market town to a national capital at the demand of furriners.

Being of a contrarian cast today myself…

Big cities have pockets of incredible vitality – and pockets of unremitting despair. So do small towns and rural areas. I think that the despair in some parts of the big city, though, seems far more mournful, because there are far more despairing people.

Proportions matter.

There are no doubt cheeful livable sections in Gary and Detroit as well as awful areas in Manhattan and SiliValley.

Not sure about Brooklyn; the way its been Gentrified it’s probably all or nothing by now.

If cities have personalities, most are going to be MPD although DC is undoubtedly full schizo. 😉

That said, the OP might be a fan of Warren Ellis comics, who has a character who speaks to cities and draws his mood and energy from them. A very violent and authoritarian character who believed he was saving the world but in the end caused its destruction.

Mexico City isn’t mournful, at least not in my memories. More full of interesting sounds and smells and people and sights – any time of day or night.

Silly PG, talking as if there were other cities besides New York. Everybody knows there aren’t, and if your lying eyes tell you there are, you blush and keep quiet about it.

Most New Yorkers that I have known acknowledge that there are other cities out there, Tom. But they’re all full of furriners.

Civilization ends at the Hudson.

The reality, though, is that the barbarian wilderness is on the eastern bank.