From Rebecca Tushnet’s 43(B)log:

This putative class action alleged that Amazon overcharged and “[d]eceived consumers by misrepresenting that it was selling them Digital Content when, in fact, it was really only licensing it to them[.]” Plaintiffs brought claims under California, New York, and Washington consumer protection law, and common law claims for unjust enrichment.

Plaintiffs alleged that Amazon offers cheaper “rent” options for some of its content, but more expensive “buy” options as well. When consumers “buy” digital content, it’s stored in a folder called “Video Purchases & Rentals.”

But, in fact, Amazon does not cannot pass title of any of this content to consumers. “If the licensing agreement for any of the Digital Content is terminated, Amazon has to pull the Digital Content from not only its site but from all consumers’ purchased folders, ‘which it does without prior warning, and without providing any type of refund or remuneration to consumers.’”

Amazon argued that Article III standing was absent because plaintiffs haven’t lost access to their digital content, and that their claims of overpayment also rested on the mere threat of future unavailability. The court disagreed: there’s a plausible difference in value between owning outright versus purchasing a revocable license.

“Buy” was also plausibly deceptive. Amazon argued that “buy” didn’t mean perpetual ownership, and that it sufficiently disclosed the risk of losing access. Plaintiffs pointed out that Amazon also allows real, non-repossessable purchases with the “Buy” button for tangible goods. Again, the court agreed with plaintiffs: it was plausible that “buy” could be materially misleading. The court hypothesized a consumer who paid nearly $40 for Barbie and Oppenheimer, but whose Barbenheimer (first judicial appearance?) weekend was ruined because Amazon suddenly lost one license. “Understandably, this consumer ‘might feel a little miffed [or go nuclear] if she were told that she received exactly what she paid for.’”

Link to the rest at Rebecca Tushnet’s 43(B)log and thanks to C. for the tip.

In former days, PG had the occasion to deal with Amazon’s in-house attorneys regarding various matters relating to his clients. He found these lawyers to be intelligent, competent and reasonable (a trifecta that not all lawyers/legal departments can pull off).

PG speculates that the mess described in the OP originated with the marketing department’s decision to proceed on a path contrary to the legal department’s strong recommendations.

In most businesses with which PG has dealt, in such battles, the marketing department often wins. After all, marketing and sales are how a company makes money, and legal is always a cost item that invariably slows down the release of new products and services (often deeply resented within corporate middle management).

Intellectual property in digital form is always licensed, not sold. One of the primary reasons for this legal/practical decision is that digital property is almost always easily duplicated—bits can multiply extremely rapidly in a digital device and thereafter be sent digitally anywhere in the world at the speed of light.

Yes, physical books can be duplicated and shipped anywhere in the world, but a printing press and lots of paper is required to do so. Therefore, you own the single printed copy of a book you purchased at Barnes & Noble (or Amazon), but you license the ebook you receive from Amazon or Barnes & Noble because they are operating under the terms of a license they have received from the indie author or a publisher which has the author’s consent to print, publish, license or sell the book.

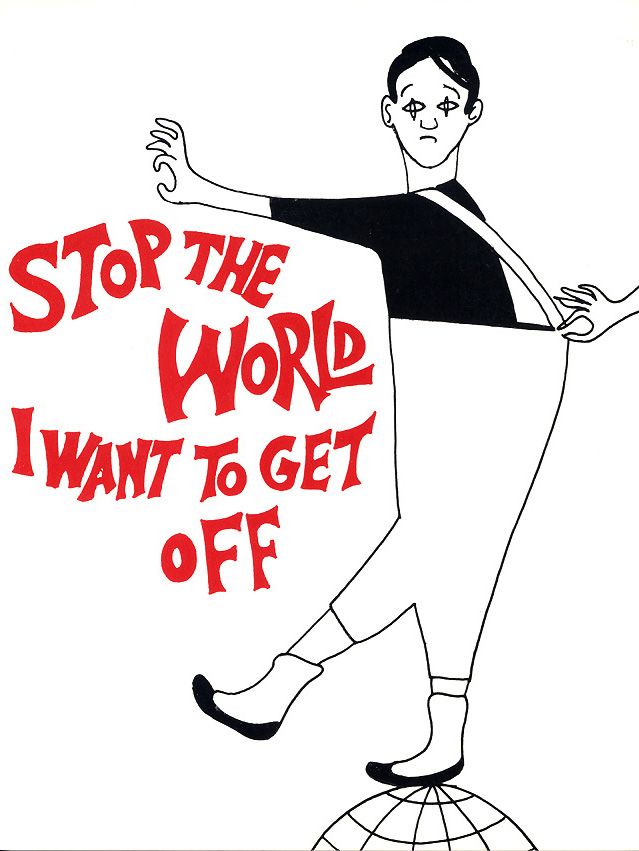

But Marketing said, “Customers will be confused if we have, ‘License now with 1-Click®‘”

End of license v. sale discourse.