We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.

Winston Churchill

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Mentor and Protégé

From Writers Helping Writers:

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it’s important to craft them carefully. But characters don’t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they’ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite—derailing your character’s confidence and self-worth—or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

. . . .

Mentor and Protégé

Description: This relationship consists of an experienced mentor who has achieved a measure of expertise in a given area and a protégé dedicated to learning from them and following in their footsteps. While a relationship can initially be established with this purpose in mind, the mentor/protégé dynamic typically grows out of an existing relationship (teacher/student, coach/athlete, boss/employee). The interactions between the two parties will differ based on many factors and may change over time.

Relationship Dynamics:

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A mentor eagerly sharing the fruits of their knowledge with the protégé

A mentor taking a personal interest in their protégé

A mentor actively creating growth opportunities for the protégé—taking them to meetings and introducing them to other influencers, etc.

A mentor being open to learning from the protégé

A mentor jealously keeping the protégé to himself

A mentor who doesn’t want the protégé to move on (seeing him or her as a valuable resource rather than someone with potential) and doesn’t do what is needed to grow them

A mentor viewing the protégé as an underling to do their busy work

A brilliant mentor who isn’t necessarily good at teaching or dealing with people

A mento taking the protégé’s lack of interest or ability personally

A protégé recognizing what the mentor can provide and soaking up everything they can

A protégé seeing the relationship not just as one that benefits him but also looking for ways he can help the mentor

A protégé catching up with their mentor and growing past him or her

A protégé taking the opportunity seriously, being responsible and showing gratitude

An overconfident protégé not being open to feedback from the mentor

A protégé seeking constant instruction, feedback, and affirmation from the mentor

A reluctant protégé only putting in partial effort

An eager protégé being distracted by personal problems and not giving the relationship their all

An unwilling protégé being pushed into the relationship (by parents, a court order, etc.), resulting in apathy or resentment

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

The mentor wanting something different for the protégé than the protégé wants

Either party wanting more time, energy, or personal attention than the other is willing or able to give

The mentor wanting to teach a protégé who is in the relationship for subversive reasons (to gain information for someone else, to set the mentor up for failure, to humiliate them, etc.)

A protégé wanting to learn from a mentor who wants to control and subdue

The protégé wanting to be taught and mentored while the mentor wants a lackey

Both parties wanting to be “top dog” in the relationship

Link to the rest at Writers Helping Writers

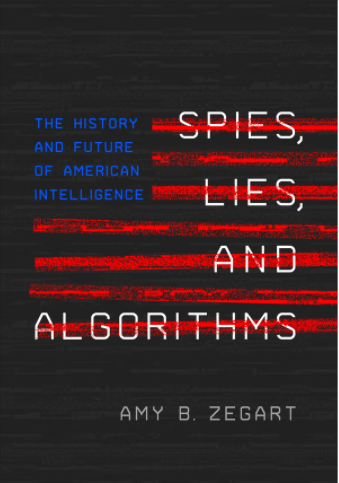

A history of free expression charts its seesawing progress

From The Economist:

A global firestorm erupted in 2005 after the publication in a Danish newspaper of 12 provocative cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad. Jacob Mchangama, a Dane and then a young lawyer, was dismayed. In the Muslim world he watched states that rarely allowed protest of any kind encourage violent demonstrations. Those governments also redoubled their diplomatic efforts to define “defamation of religions” as a human-rights violation that should be banned everywhere.

He found the response elsewhere even more alarming. Respectable people across the Western world blamed the cartoonist and his editors, not the repressive forces that drove the newspaper staff into hiding. This was not what Mr Mchangama, the product of a confidently secular Nordic democracy, had expected.

As his new book recalls, free expression was suffering setbacks on other fronts, too. In the late 1990s, when he was a student, the internet presaged a glorious era of liberty for people who otherwise lacked money or power to speak and organise. The victory in 2008 of Barack Obama, an erstwhile outsider, marked a high point of those expectations. Even then, though, digital freedom was already in retreat. Authoritarian regimes proved adept at exploiting and policing social media for their own malign ends. Western governments were often heavy-handed in their regulation of extremist discourse. And the gigantic power wielded by a few tech companies was troubling, regardless of how they used it.

All this led Mr Mchangama (whose paternal forebears came from the Comoro Islands) to apply his legal mind to supporting intellectual liberty: by podcasting and founding a think-tank, and by studying free expression’s fluctuating fortunes over the past 25 centuries. His conclusions, presented in a crisp and confident march through Western history, are sobering.

His view that freedom of speech is under threat from many directions—and, politically, from both right and left—is not original. More distinctive is his determination to show the ebb and flow of liberty as a dynamic process, under way at least since the era of ancient Greece. Accordingly, stringent repression of thought and speech becomes self-defeating and stimulates brave opponents. But great bursts of freedom also prove finite.

For example, the intellectual energy unleashed by the printing press and the Protestant Reformation was dissipated in waves of sectarian wars and mutual persecution. After the shock of the American and French revolutions, and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, Britain’s establishment became severely repressive in the early 19th century. But a countervailing movement of liberal thought and debate, carried along by technological and social change, proved more powerful.

Yet that trend, too, had its limits and its hypocrisies. John Stuart Mill was a brilliant Victorian advocate of intellectual freedom, but he participated in, and defended, the colonial administration of India. And as Britain became more open and tolerant at home, it curbed liberty of expression in its overseas possessions, especially amid the rise of independence movements.

The effects of colonial repression continued to be felt long after colonialism ended, as the book shows. Laws dating from the British Empire have been used to stifle dissent in modern India, and recently in Hong Kong. Measures that strangle freedom can easily outlive the conditions that engendered them—as, luckily, can laws and constitutions that entrench liberty. In America, where the possibility of frank, productive debate seems threatened by cultural warfare, the constitution’s First Amendment sets a limit on any faction’s ability to muzzle its opponents.

Link to the rest at The Economist

Stalin’s Library

From The Wall Street Journal:

Edward Gibbon sits proudly upon my bookshelf. A set of volumes that I own, neatly stacked, comprises his “History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.” What do you make of me because it is there? The set might indicate that I am a classicist, a scholar. It could signal my ambition—or my vanity. Perhaps it marks me as an anachronism: In this impatient, up-to-the-second moment, I display something written almost 250 years ago about a subject that is itself far older. While you form your judgment, let me divulge a secret. I have not read to the end of the famous series. Somewhere between Julian’s residence at Antioch and the revolt of Procopius, I lost the thread and laid Gibbon aside.

A famous reader who is the subject of a fascinating new study would have sniffed me out. Joseph Stalin went into the libraries of Communist Party officials to see if their books had truly been read or merely served to decorate the room. Stalin prized his own books and used bookmarks rather than dog-earing a page, good man. Yet his literary hygiene was not above reproach. One lender complained that Stalin smudged the pages of books with greasy fingerprints. As the party’s general secretary, he sometimes disregarded due dates. After he died in 1953, many of the volumes he had borrowed from the Lenin Library were quietly returned, the late fees unpaid.

Why should this matter of a cruel tyrant responsible for the deaths of millions of people? Geoffrey Roberts, a professor emeritus of history at University College Cork in Ireland, notes in “Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and His Books” that Stalin kept no diary and wrote no memoirs. Therefore his personal library, which he carefully maintained and treasured, offers a unique window into his thoughts. “Through an examination of these books,” Mr. Roberts writes, “it is possible to build a composite, nuanced picture of the reading life of the twentieth century’s most self-consciously intellectual dictator.”

That is a complex claim. Mr. Roberts doesn’t assert that Stalin’s books or the marks he made in them hold the key to his psyche. And the word “intellectual” will raise an eyebrow—the man was as coarse as smashed rocks—although “self-consciously” is an essential qualifier. Stalin wasn’t a gifted rhetorician or purveyor of original ideas like his contemporaries Lenin and Trotsky, yet he lived in their highbrow shadow. Mr. Roberts writes that “complexity, depth and subtlety” were not his strengths. Instead, his “intellectual hallmark was that of a brilliant simplifier, clarifier and popularizer.” The American diplomat Averell Harriman observed that Stalin possessed “an enormous ability to absorb detail.” He came to meetings “extremely well-informed.”

. . . .

Books were his secret weapon. During World War II, Stalin read widely on topics like military strategy, artillery and field tactics. At other times, he devoured volumes on history and Marxism. He had always been a reader, Mr. Roberts says. As a boy, Stalin was a bookworm; in the seminary, he was censured for reading forbidden novels on the chapel stairs. His daughter, Svetlana, said that in his Kremlin apartment there was scarcely room for art on the walls because they were lined with encyclopedias, textbooks and pamphlets, many well-thumbed. Stalin often asked others what they were reading and was known to interrupt meetings by taking down a volume of Lenin’s to “have a look at what Vladimir Ilyich has to say.”

At the time of his death, Mr. Roberts estimates, Stalin’s personal library ran to approximately 25,000 books, pamphlets and periodicals. Roughly 11,000 were classics of Russian and world literature by authors like Pushkin, Gogol, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Hugo and Shakespeare. The remainder were nonfiction titles in Marxism, history, economics and other fields. Lenin was far and away the most represented author, at nearly 250 publications—there were also scores of works by Bukharin, Trotsky and Engels. Stalin had his own ex-libris stamp and classification system. The centerpiece of his Moscow residence was its library, although he preferred to store his collection off-site and have an assistant bring him reading material upon request.

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)

How Emotionally Intelligent People Use the ‘Emotional Postmortem’ to Control Their Emotions and Improve Their Relationships

PG thought this item might be useful for character-building.

From Inc.:

“Oh, boy. This time I messed up.”

That’s what I was thinking when some years ago, I let my emotions get the best of me. I believed a colleague had stolen something of mine. Not literally; I thought he stole an idea. At least, that’s how I felt.

I knew the way I should handle it. I knew I should approach him calmly, state my concern without any type of accusation, and give him the chance to explain the situation.

But that’s not what I did.

Instead, I went in like a ticking time bomb, asking emotionally charged questions before …

I went off.

In the end, it turned out to be a huge misunderstanding. I felt horrible, because the colleague was a nice guy, and up until that moment we had a pretty good relationship. Of course, I apologized profusely, and he said it was OK and we’d consider it water under the bridge.

But to this day, every time I think of that moment, I cringe.

If you’ve ever had a moment like this one, maybe you can relate. In emotional intelligence terms, we refer to this as an emotional hijack.

In an emotional hijack, a small part of your brain known as the amygdala, which serves as a type of emotional processor, “hijacks” your brain and causes you to react without thinking. In my case, some built-up tension and various other factors caused me to see a situation unclearly, jump to conclusions, and hurl harsh accusations at a colleague.

It’d be great if we could identify the circumstances that lead up to emotional hijacks before they happen, but that’s not usually how it works. But learning to analyze an emotional hijack after it happens can be almost as valuable.

I like to call this process the “emotional postmortem.”

Just like a medical or project postmortem, the goal of an emotional postmortem is to determine the cause of “death,” or failure. When you identify the cause for a hijack, you can devise a plan to help you avoid repeat episodes in the future.

Link to the rest at Inc.

Public Domain Day 2022

From The Duke University School of Law:

In 2022, the public domain will welcome a lot of “firsts”: the first Winnie-the-Pooh book from A. A. Milne, the first published novels from Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner, the first books of poems from Langston Hughes and Dorothy Parker. What’s more, for the first time ever, thanks to a 2018 law called the Music Modernization Act, a special category of works—sound recordings—will finally begin to join other works in the public domain. On January 1 2022, the gates will open for all of the recordings that have been waiting in the wings. Decades of recordings made from the advent of sound recording technology through the end of 1922—estimated at some 400,000 works—will be open for legal reuse.

. . . .

Why celebrate the public domain? When works go into the public domain, they can legally be shared, without permission or fee. That is something Winnie-the-Pooh would appreciate. Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can perform the music publicly, without paying licensing fees. Online repositories such as the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, and Google Books can make works fully available online. This helps enable access to cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history. 1926 was a long time ago. The vast majority of works from 1926 are out of circulation. When they enter the public domain in 2022, anyone can rescue them from obscurity and make them available, where we can all discover, enjoy, and breathe new life into them.

The public domain is also a wellspring for creativity. The whole point of copyright is to promote creativity, and the public domain plays a central role in doing so. Copyright law gives authors important rights that encourage creativity and distribution—this is a very good thing. But it also ensures that those rights last for a “limited time,” so that when they expire, works go into the public domain, where future authors can legally build on the past—reimagining the books, making them into films, adapting the songs and movies. That’s a good thing too! As explained in a New York Times editorial:

When a work enters the public domain it means the public can afford to use it freely, to give it new currency . . . [public domain works] are an essential part of every artist’s sustenance, of every person’s sustenance.

Just as Shakespeare’s works have given us everything from 10 Things I Hate About You and Kiss Me Kate (from The Taming of the Shrew) to West Side Story (from Romeo and Juliet), who knows what the works entering the public domain in 2022 might inspire? As with Shakespeare, the ability to freely reimagine these works may spur a range of creativity, from the serious to the whimsical, and in doing so allow the original artists’ legacies to endure.

. . . .

Books

- A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh, decorations by E. H. Shepard

- Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

- Dorothy Parker, Enough Rope (her first collection of poems)

- Langston Hughes, The Weary Blues

- T. E. Lawrence, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (later adapted into the film Lawrence of Arabia)

- Felix Salten, Bambi, A Life in the Woods

- Kahlil Gibran, Sand and Foam

- Agatha Christie, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

- Edna Ferber, Show Boat

- William Faulkner, Soldiers’ Pay (his first novel)

- Willa Cather, My Mortal Enemy

- D. H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent

- H. L. Mencken, Notes on Democracy

. . . .

Movies Entering the Public Domain

- For Heaven’s Sake (starring Harold Lloyd)

- Battling Butler (starring Buster Keaton)

- The Son of the Sheik (starring Rudolph Valentino)

- The Temptress (starring Greta Garbo)

- Moana (docufiction filmed in Samoa)

- Faust (German expressionist classic)

- So This Is Paris (based on the play Le Réveillon)

- Don Juan (first feature-length film to use the Vitaphone sound system)

- The Cohens and Kellys (prevailed in a famous copyright lawsuit)

- The Winning of Barbara Worth (a Western, known for its flood scene)

Musical Compositions

- Bye Bye Black Bird (Ray Henderson, Mort Dixon)

- Snag It (Joseph ‘King’ Oliver)

- Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Irving Berlin)

- Black Bottom Stomp (Ferd ‘Jelly Roll’ Morton)

- Someone To Watch Over Me (George Gershwin, Ira Gershwin)

- Nessun Dorma from Turandot (Giacomo Puccini, Franco Alfano, Giusseppe Adami, Renato Simoni)

- Are You Lonesome To-Night (Roy Turk, Lou Handman)

- When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin’ Along (Harry Woods)

- Ke Kali Nei Au (“Waiting For Thee”) (Charles E. King), in 1958 renamed Hawaiian Wedding Song with new lyrics (English) by Hoffman & Manning

- Cossack Love Song (Otto Harbach, Oscar Hammerstein II, George Gershwin, Herbert Stothart)

Link to the rest at The Duke University School of Law

Happy Public Domain Day!

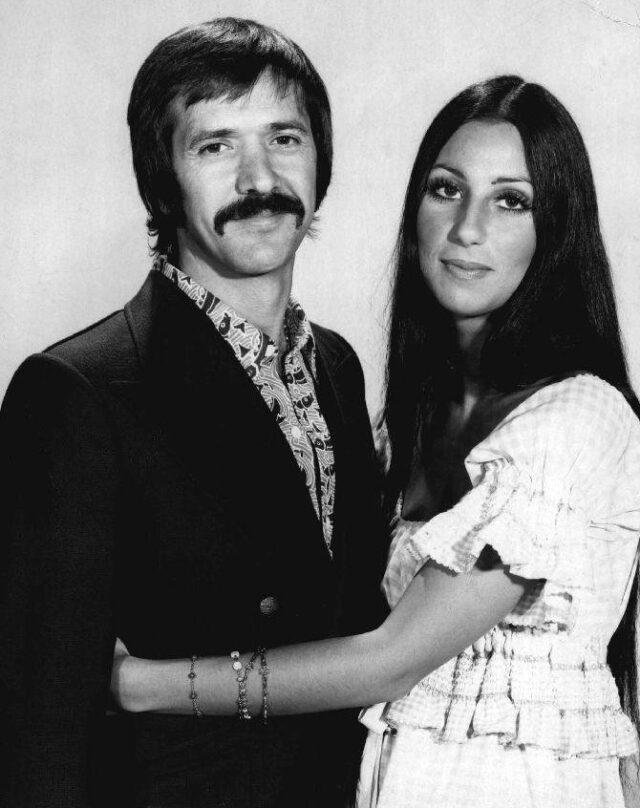

From Cory Doctorow via Medium:

On January 1, 2019 something extraordinary happened. For the first time since 1998, the American public domain got bigger.

What happened in 1998? Congress — led by Rep Sonny Bono — extended the copyright on all works by 20 years. Works that had already been in the public domain went back into copyright. Works that were in copyright got an extra 20 years. The public domain…froze.

This was a wanton, destructive act. The vast majority of works that the Sonny Bono Act covered were out-of-print and orphaned, with no known owner. Putting them back into copyright for 20 years prevented their reproduction, guaranteeing that many would vanish from the historical record altogether.

As to the minuscule fraction of works covered by the Act that were still commercially viable: the creators of those works had accepted the copyright bargain of life plus 50 years. Giving them more copyright on works they’d already produced could not provide an incentive to make anything more. All it did was transfer value from the public domain into a vanishing number of largely ultra-wealthy corporate private hands.

As to living, working creators: those who’d made new works based on public domain materials that went back into copyright found themselves suddenly on the wrong side of copyright. Their creative labor was now illegal. Any working, living creator that contemplated making a new work based on material from the once-public-domain was now faced with tracking down an elusive (or possibly nonexistent) rightsholder, paying lawyers to negotiate a license, and subjecting their work to the editorial judgments of the heirs of long-dead creators.

The Sonny Bono Act is often called the Mickey Mouse Act, a recognition of the extraordinary blood and treasure that Disney spilled to attain retroactive copyright extension. This extension ensured that Steamboat Willie — and subsequent Mickey Mouse cartoons, followed by other Disney products — would remain Disney’s for another two decades.

Link to the rest at Cory Doctorow via Medium

PG would modify the factual description in the OP with a small change - The Sonny Bono Act was pushed through by California congresswoman Mary Bono (Sonny Bono’s widow and Congressional successor). Sonny served from 1995-98 and Mary, after winning a special election to become Sonny’s replacement, served from 1998-2013 after she failed to win another re-election.

Prior to getting into politics, Sonny was a musical performer, the less-talented half of Sonny & Cher.

Sonny and Cher divorced in 1975 due to Sonny’s serial affairs with other women. Prior to marrying Sonny, his second wife, Mary, later Congresswoman Bono, had worked as a cocktail waitress and fitness instructor.

Sonny and Mary each represented the congressional district dominated by Palm Springs and nearby Palm Desert, retirement destinations for the wealthy and semi-wealthy which include a number of retired actors. Author Ann Rice (Interview with the Vampire, etc.) lived in Palm Springs until her death in 2021.

PG suggests the Bonos are yet another “only in California” stories.

Why good thoughts block better ones: the mechanism of the pernicious Einstellung effect

From The National Library of Medicine via PubMed:

Abstract: The Einstellung (set) effect occurs when the first idea that comes to mind, triggered by familiar features of a problem, prevents a better solution being found. It has been shown to affect both people facing novel problems and experts within their field of expertise. We show that it works by influencing mechanisms that determine what information is attended to. Having found one solution, expert chess players reported that they were looking for a better one. But their eye movements showed that they continued to look at features of the problem related to the solution they had already thought of. The mechanism which allows the first schema activated by familiar aspects of a problem to control the subsequent direction of attention may contribute to a wide range of biases both in everyday and expert thought - from confirmation bias in hypothesis testing to the tendency of scientists to ignore results that do not fit their favoured theories.

Link to the rest at PubMed

From Wikipedia:

Einstellung literally means “setting” or “installation” as well as a person’s “attitude” in German. Related to Einstellung is what is referred to as an Aufgabe (“task” in German). The Aufgabe is the situation which could potentially invoke the Einstellung effect. It is a task which creates a tendency to execute a previously applicable behavior. In the Luchins and Luchins experiment a water jar problem served as the Aufgabe, or task.

The Einstellung effect occurs when a person is presented with a problem or situation that is similar to problems they have worked through in the past. If the solution (or appropriate behavior) to the problem/situation has been the same in each past experience, the person will likely provide that same response, without giving the problem too much thought, even though a more appropriate response might be available. Essentially, the Einstellung effect is one of the human brain’s ways of finding an appropriate solution/behavior as efficiently as possible. The detail is that though finding the solution is efficient, the solution itself is not or might not be.

Another phenomenon similar to Einstellung is functional fixedness (Duncker 1945). Functional fixedness is an impaired ability to discover a new use for an object, owing to the subject’s previous use of the object in a functionally dissimilar context. It can also be deemed a cognitive bias that limits a person to using an object only in the way it is traditionally used. Duncker also pointed out that the phenomenon occurs not only with physical objects, but also with mental objects or concepts (a point which lends itself nicely to the phenomenon of Einstellung effect.

Link to the rest at Wikipedia

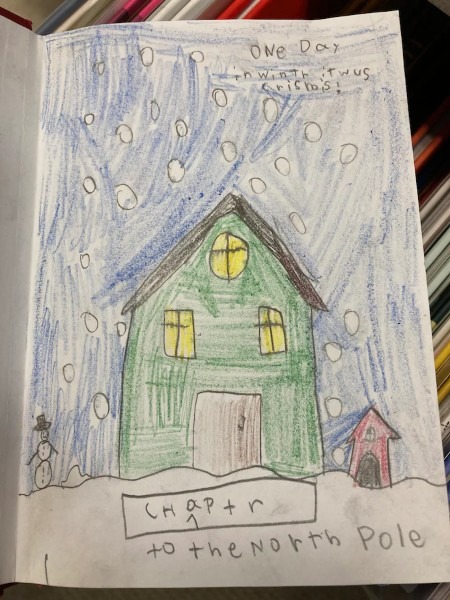

An 8-year-old slid his handwritten book onto a library shelf. It now has a years-long waitlist.

From The Washington Post:

Dillon Helbig, a second-grader who lives in Idaho, wrote about a Christmas adventure on the pages of a red-cover notebook and illustrated it with colored pencils.

When he finished it in mid-December, he decided he wanted to share it with other people. So much, in fact, that he hatched a plan and waited for just the right moment to pull it off.

Days later, during a visit to the Ada Community Library’s Lake Hazel Branch in Boise with his grandmother, he held the 81-page book to his chest and passed by the librarians. Then, unbeknown to his grandmother, Dillon slipped the book onto a children’s picture-book shelf. Nobody saw him do it.

“It was naughty-ish,” Dillon, 8, said of covertly depositing the book without permission. But the result, he added, is “pretty cool.”

The book, titled “The Adventures of Dillon Helbig’s Crismis,” is signed “by Dillon His Self.”

He later confessed to his mother, Susan Helbig, that he slid his book into the stacks and left it there, undetected. But when they returned about two days later, to the spot where he left the notebook, it was missing. Helbig called the library to ask whether anyone had found Dillon’s notebook and to request that they please not throw it away.

Branch manager Alex Hartman said he was surprised at Dillon’s bold move.

“It was a sneaky act,” said Hartman, laughing. But Dillon’s book “was far too obviously special an item for us to consider getting rid of it.”

Hartman and a few co-workers had discovered and read Dillon’s book — which describes his adventures putting an exploding star on his Christmas tree and being catapulted back to the first Thanksgiving and the North Pole. They found it very entertaining.

Hartman read the book to his 6-year-old son, Cruzen, who giggled and said it was one of the funniest books he’d ever known.

“Dillon is a confident guy and a generous guy. He wanted to share the story,” Hartman said. “I don’t think it’s a self-promotion thing. He just genuinely wanted other people to be able to enjoy his story. … He’s been a lifelong library user, so he knows how books are shared.”

The staff librarians who read Dillon’s book agreed that as informal and unconventional as it was, the book met the selection criteria for the collection in that it was a high-quality story that was fun to read. So, Hartman asked Helbig for permission to tack a bar code onto the book and formally add it to the library’s collection.

Dillon’s parents enthusiastically said yes, and the book is now part of the graphic-novels section for kids, teens and adults. The library even gave Dillon its first Whoodini Award for Best Young Novelist, a category the library created for him, named after the library’s owl mascot.

. . . .

As luck would have it, the lone copy of “The Adventures of Dillon Helbig’s Crismis” has become a book in demand.

KTVB, a news station in Boise, reported on Dillon’s book caper earlier this month, and since then, area residents have begun adding themselves to a waiting list to check it out. As of Saturday, there was a 55-person waitlist.

. . . .

Dillon is also writing a different book about a closet that eats up jackets.

Link to the rest at The Washington Post

There is nothing like the death of a moneyed member of the family

There is nothing like the death of a moneyed member of the family to show persons as they really are, virtuous or conniving, generous or grasping. Many a family has been torn apart by a botched-up will. Each case is a drama in human relationships — and the lawyer, as counselor, draftsman, or advocate, is an important figure in the dramatis personae. This is one reason the estates practitioner enjoys his work, and why we enjoy ours.

Jesse Dukeminier and Stanley M. Johanson, estate planning attorneys

Books about Estate Planning and Authors

PG took a look on Amazon to locate books on the topic. He hasn’t reviewed any of these books and warns one and all that a book is not a substitute for a competent attorney familiar with estate planning and intellectual property issues.

One caveat - While the Federal Estate Tax is uniform across all states, each state has its own laws governing estates and trusts and its own laws regarding the probate of wills and state inheritance taxes. Some states don’t have state inheritance taxes.

This is why, you’ll want to look for an attorney who is experienced estate planning in your state. Should you move to a different state after creating a will and/or trust, you’ll want to have an experienced estate planning attorney practicing in your new state domicile review your current estate plan documents.

A Primer on Estate Planning as a Writer

From Jane Friedman:

Awareness of estate planning issues can be especially important to writers because of the unique nature of property rights in written works. Proper planning ensures that the ownership of a writer’s works after his or her death will end up in safe and knowledgeable hands.

In addition to giving the writer significant posthumous control over his or her works, an estate plan can greatly reduce the overall amount of estate tax paid at death. Because valuations of written works for estate tax purposes are not precise, estate taxes may turn out to be significantly higher than might have been anticipated. Thus, it is very important for writers to reduce their taxable estate as much as possible.

An estate plan may be either will-based or trust-based. Each type has advantages, but both are legitimate forms of estate planning. Estate laws and probate procedures vary throughout the United States, and a plan that works well for one person in one state may be inappropriate in other situations. Proper estate planning requires a knowledgeable lawyer and sometimes the assistance of other professionals, such as life insurance agents, accountants, and bank trust officers.

The Will

A will is a unique document in two respects. First, if properly drafted, it is ambulatory, meaning it can accommodate change, such as applying to property acquired after the will is made. Second, it is revocable, meaning it can be changed or canceled before death.

When carefully prepared, wills not only address how the assets of the estate will be distributed, but also foster better management of the assets. Those persons responsible for administering the estate of a decedent are known as executors in some states and personal representatives in others. It may be a good idea for writers to appoint joint executors so that one has publishing or writing experience and the other has financial expertise. In this way, the financial decisions can have the benefit of at least two perspectives. If joint executors are used, it will be necessary to make some provision in the will for resolving any deadlock between the two. A lawyer’s help will be necessary to set forth all of these important considerations in legally enforceable, unambiguous terms.

It is essential to avoid careless language that might be subject to attack by survivors unhappy with the will’s provisions. A lawyer’s help is also crucial to avoid making bequests that are not legally enforceable because they are contrary to public policy.

Trusts

A common way to transfer property outside the will is to place the property in a trust that is created prior to death. A trust is simply a legal arrangement by which one person holds certain property for the benefit of another. The person holding the property is the trustee; those who benefit are the beneficiaries.

To create a valid trust, the writer must identify the trust property, make a declaration of intent to create the trust, transfer property to the trust (this is often a step that is missed and can create a multitude of problems), and name identifiable beneficiaries. Failure to name a trustee will not defeat the trust, since if no trustee is named, a court will appoint one. (The writer may name himself or herself as trustee.)

Trusts can be created by will, in which case they are termed testamentary trusts, but these trust properties will be probated along with the rest of the will. To avoid probate, the writer must create a valid inter vivos or living trust.

Advantages of Using a Trust

The use of trusts to prepare a trust-based plan will, in certain situations, have significant advantages over a traditional will-based plan. For example, the careful drafting of trusts can allow the writer’s estate to avoid probate, which in some states is a lengthy and expensive process. Similarly, the execution of an estate through a trust-based plan can ensure a level of privacy not possible in probate court. Although these kinds of provisions provide some control over the estate, writers are cautioned that trusts cannot adequately substitute for a will if used haphazardly. Professional assistance is strongly recommended.

Link to the rest at Jane Friedman

PG says that dying without a will and/or trust usually ends up being the most expensive and time-consuming way of handling an estate for an author or anyone else.

That said, a poorly-drafted will can also cause an immense amount of difficulty and expense.

As mentioned previously, you’re looking for an estate planning attorney who can answer your questions, including questions about state and federal death taxes and how to minimize them.

Large law firms will have estate planning attorneys, but are likely to charge more for a similar service than a medium-sized or smaller law firm. That said, the amount of the fee a large firm charges for creating an estate plan will cost less than a legal dispute about your estate after you die.

As mentioned in comments to a prior post, you will want to make certain your estate-planning attorney is familiar with the special issues that can arise with intellectual property. If you have any concerns about an estate planning attorney’s appreciation of copyright issues, it will be worth it to ask her/him to associate counsel specializing in intellectual property, preferably copyright law (as opposed to patents, trademarks, trade secrets, etc.).

PG suggests accessing online information about authors and estate planning to become generally familiar with issues, jargon, etc. Check more than one or two sites so you’re not getting someone’s pet theories, peeves, etc.

For the record, although PG has done some estate planning for authors and others, he doesn’t do so any more.

Estate Planning for Authors

Since PG’s previous post about authors and their estates generated some good comments, he decided to post again on the topic.

The leading cause of death

The leading cause of death among fashion models is falling through street grates.

Dave Barry

When a Writer Dies: Making Difficult Decisions About the Work Left Behind

From Jane Friedman:

Nine days before my wife died, she forwarded me a Brevity post, The Death of a Writer, which asked:

Who is going to deal with your literary legacy, and what do you want done?

My wife wrote, “…interesting re what to do…”

She added a lifesaver emoji.

My wife, Mary Ann Hogan, journalist and teacher, died June 13, 2019, her “tango with lymphoma” ended, her life’s literary work unfinished.

Her manuscript explored her relationship with her father, William Hogan, longtime literary editor of the San Francisco Chronicle. Though he spent his life writing about books, Bill Hogan never wrote one of his own.

Mary Ann died thinking her book would redeem them both.

. . . .

My wife’s friends and writing partners agreed to help me read and judge what to save for the book or elsewhere. Then there would be drafts of the book to react to and fact-check. Her posse was more than willing. Mine, too.

We puzzled over things such as:

Should the final chapter be in my voice or hers? Both, we said. I would not pretend to be her. But I would quote her all the time, and we found those quotes.

What about the references to mental illness? She talked about panic attacks and flying thoughts, but never named the various diagnoses. What about wine? She talked about how she and her father all were big drinkers, without details. Leave it as she wrote it, we said.

What about the title? Circle Way came from the posse. Larger illustrations? That idea came from her writing mentor.

Rewrites? Mary Ann had created a lyric essay that jumped around like Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, becoming at times a duet with her late father’s journal entries. This mosaic, we said, is best as is.

There’s more of her work to publish, in time, and now that we have a system, it can happen.

Finishing Mary Ann’s manuscript was not as hard as finding the right publisher. Parts of Circle Way had won three writing competitions. Publishers said it was “beautiful.” They also said it was “too literary” for the commercial marketplace.

My promise to my wife—to finish her book—felt shattered.

Now what?

Link to the rest at Jane Friedman

PG won’t spend much time on this, but talk to an attorney and get a will and/or a trust in place before you die or become incapacitated. Dying without a will is the most time-consuming and expensive way of passing your assets on to your heirs.

Writing a will is anything but rocket science, but if you have significant assets (more than a few hundred thousand dollars) or unusual types of property (like books you have written and self-published or books you’ve had published by any sort of publisher because whoever inherits the rights to those books will be able to collect royalties on them for the next 70 years in the US and a similarly long time in other nations recognizing copyright), the amount of money you spend to talk to an attorney and get her/his assistance will be tiny compared to the legal expenses of cleaning up an estate that hasn’t been handled properly.

Amazon is closing Westland, the Indian publishing company it acquired in 2016. What will happen to its catalogue and authors?

From The New Publishing Standard:

Amazon’s latest triumph of hope over experience comes to an end with the slow realisation that the India publishing industry, even if you own the largest digital platform in the world and have bought a successful home-grown publishing house with some of the country’s biggest author brands, is not a get rich quick scheme.

India has long been a triumph of hope over experience for Amazon, which has invested billions in the hope of one day returning profit from this huge market of 1.4 billion people, 755 million of whom are online.

. . . .

We don’t know, and likely never will, whether Westland ran at a loss for Amazon, but we can safely say Amazon is taking a loss by not selling on the company, rather choosing to close it down and absorb the human assets into the system. That of course being a reflection of how Amazon does business, not of Westland. Amazon buys, grows and profits from its acquisitions or buries them, to ensure a competitor doesn’t pick up the pieces.

In this case Amazon acquired Westland from Tata Trent back in 2016, and of course used its own platform to promote the books of its publishing company, just as it does APub – although interestingly Amazon never sought to meld Westland with APub.

New Tools: Indie Publishing

From Kristine Kathryn Rusch:

A theme of this year in review has been the hard split between indie publishing and traditional publishing. That split became clear in the numbers in 2021. The industry is no longer one industry. It’s at least two, maybe more.

But for now, we’ll go with two—indie and traditional. And one thing that has always separated these two industries is their willingness to grow and change. Indies are willing to change; traditional publishers are not.

One reason is that indie writers, in particular, are nimble enough to try new things and not have those things wreck their businesses or their business plans. An indie writer can take a book and make it exclusive in a new service for six months, and learn something. A traditional publisher has to make a legal commitment and usually cannot leave whatever service they’ve joined for a particular amount of time.

That makes sampling new tech and new software very difficult.

Also, much of the new tech is designed for the nimble indie, not for the big bloated traditional publisher. Which is why the new tools section is part of the indie publishing section of my year in review.

Many of these new tools are useless to traditional publishers. Others are impossible to sample, because the licensing agreements (contracts) those publishers have with their authors did not envision the latest, newest grandest thing. (That “any new tech anywhere in the universe” clause usually doesn’t cut it.)

. . . .

Bookstores

Generally speaking, the bookstores that survived that initial pandemic shut down from March to mid-summer 2020 are leaner and a lot more tech savvy. These stores, for the most part, are run by younger people. The older bookstore owners retired in that tough period or sold their stores. A lot of stores closed, particularly used stores. (Which is the position that Las Vegas is in. We had three used bookstores before March of 2020, and none now.)

Again, generally speaking, the new younger booksellers are more open-minded, a lot more willing to use the internet for everything from ordering to shipping, and receptive to local authors, even those not traditionally published.

All the information I have on this is either anecdotal or from the mists of my summer business reading. The good news here, though, is that indies who have paper editions can probably get them into a local bookstore, if only for a short time, provided the books look good (so many indie-designed paper books do not, even with all the best tools in the world), and provided the indie is willing to work with the store.

. . . .

One other U.S. bookstore development features Barnes & Noble, a company that seems to me like a mash-up between the Black Knight from Monty Python and The Holy Grail (“I’m fine”) and another Holy Grail sequence (“Not Dead Yet”). Barnes & Noble’s CEO since 2019, James Daunt, used the 2020 bookstore closures to remodel and remake the stores.

Then he did something rather brilliant—he returned control of each store to the local managers. They are now stocking books that locals ask for and want, rather than relying on corporate for ordering. Relying on corporate for ordering allowed B&N in the bad old days to get deep discounts on books, but it also meant that each store looked the same no matter where you went. And if a local author’s books were not in the store, nothing anyone could do would get them there. A special order only brought in one copy.

That’s changed, for right now anyway. Anecdotal reports are that the bookstores look bright and clean and full. The content is different from store to store, which makes the stores interesting.

From a writer’s point of view, suddenly the local chain store might be willing to order copies of a good-selling ebook or of a local author’s work for their local author section (if they have one). Writers actually have a chance to get their books into a brick-and-mortar store, at least one near their home.

Does all of this mean that B&N will stick around? Hell if I know. I don’t know if their balance sheet is good or bad anymore or what the changes mean.

But for 2022, anyway, the outlook is bright for anyone who wants to get their books into a nearby B&N. For what it’s worth.

Ebookstores

There are so many now that I can’t keep track. Companies here, there, and everywhere. Any indie who is not using tools like Draft2Digital to upload their books to very small e-retailers is missing an important cash stream. It seems that every time I go on D2D or, more often, use its referral arm, Books2Read, I see yet another store I haven’t heard of.

So the continual growth of e-retailers is something that has gone on for years now. But the biggest change on this front isn’t the retail companies. It’s the success of retail stores on individual author sites.

This is anecdotal, of course, because there’s no way to aggregate it. But the pandemic changed buying habits, introducing a lot of reluctant people to buying from sites other than the big retailers like Amazon and Walmart. That change in buying habits means that a lot of readers want to buy directly from the author.

So individual online bookstores went from being a silly waste of time to something that provides writers with their purest income—no one takes a percentage from their online store. The writers can control pricing, sales, and everything else.

It helps that online stores are easy to build now. There are a lot of tools that reduce the build to an easy upload, and a click or two. These programs also provide a secure checkout as well.

If you haven’t tried any of the online store programs for the past five years or so, then you’ll be surprised at how easy it all is for writer and consumer alike. I personally think this will be one of the major growth areas of 2022.

If there are only one or two things you can add to your plate this year, make designing and maintaining an online ebook store one of them.

Book Design Tools

Every few years or so there is a major improvement in indie book design. The last one I was aware of was the arrival of Vellum, a software program for Macs only. At first, Vellum was only for ebooks, and then it expanded to paper books. The Mac users swore by it, and I know that WMG changed a lot of its templates so that we could use Vellum, saving hours and hours of work on each book.

But, as I said above, Vellum is Mac-only. PC users bitched about that. There was a workaround—they could use Mac on cloud, but it had problems that made the workaround uncomfortable at best.

Now there’s Atticus, which works on all platforms, or so it says. The PC people are excited about it for that reason. But I’m also hearing that it’s a good design program.

Honestly, it really doesn’t matter if it’s good or not. Because next year, there will be another program, and two years from now, another. We’ve moved out of the stage where everyone who is publishing indie is using the same tools for the same work. We’re not even doing the same work—which is probably a topic for a future blog post.

As I’ve mentioned in this series, the longer we indies exist, the more companies try to cater to us. Or rather, to all of us in the arts. For a long time, Adobe offered the best platform to help with design and producing ebooks.

Other products either didn’t have the reach or the level of protocols. That’s changing. Affinity has become very competitive, and I know of several designers who prefer their ecosystem. I’m sure we will end up with more such tools as the decade progresses.

Link to the rest at Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Here’s a link to Kris Rusch’s books. If you like the thoughts Kris shares, you can show your appreciation by checking out her books.

6 Cheats to “Tell” Well (When It’s Warranted)

From Writers Helping Writers:

Most of us are familiar with the “Show, don’t Tell” rule. In short, it’s more effective to dramatize the story than to simply tell what happened. Nonetheless, almost every story needs at least some telling. It can help keep the pacing tight, relay background information, and enhance tone, among other things. Here’s more on when breaking the rule can work. So how do we tell well? Here are six cheats to help you.

1. Appeal to the Senses

Good showing appeals to the senses. Basically, we have to appeal to the senses to really show a story. There is no reason moments of telling can’t appeal to the senses in a similar way. Appealing to sight, sound, smell, taste, or touch can strengthen your telling just as it does with showing. It’s just that with telling, it’s usually brief, or relayed “in passing.” This example appeals to senses despite it being a telling summary:

We drove through Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, stopping to cool the engine in towns where people moved with arthritic slowness and spoke in thick strangled tongues . . . At night we slept in boggy rooms where headlight beams crawled up and down the walls and mosquitoes sang in our ears, incessant as the tires whining on the highway outside. – This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff

2. Use Concrete Metaphors and Similes

Some telling doesn’t lend itself to the senses very easily, because of the subject matter that needs to be told. In cases like that, you can try tying in a concrete comparison to suggest a sense. This example tells about a telepathic and emotional connection using comparisons:

At night awake in bed, he’d remember her presence. How their minds had been connected, ethereal like spider webs. How just her being there brought a sense of comfort, like a childhood blanket he hadn’t realized he’d still had.

3. Sprinkle in Details

Just as you use detail to make your showing great, you can and often should include detail in passages of telling. Mention a red leather jacket here or a specific cologne there. Of course, you won’t be including as much detail as you would with showing, but detail makes telling more realistic. One key to making this work is to pick the right details, as opposed to generic ones.

Their mom had always stressed the importance of eating dinner as a family, of stir fry nights and cloth napkins on laps, of hands held in prayer and laughter pealing off travertine, and even of the occasional green bean food fight.

Link to the rest at Writers Helping Writers

Who owns how much of Harry Potter?

From The New York Times (9 February 2008):

On Friday, a lawyer named Anthony Falzone filed his side’s first big brief in the case of Warner Bros. Entertainment and J.K. Rowling v. RDR Books. Falzone is employed by Stanford Law School, where he heads up the Fair Use Project, which was founded several years ago by Lawrence Lessig, perhaps the law school’s best-known professor. Falzone and the other lawyers at the Fair Use Project are taking the side of RDR Books, a small book publisher in Muskegon, Michigan, which is the defendant.

As you can see from the titans who have brought the suit, RDR Books needs all the legal firepower it can muster.

As you can also probably see, the case revolves around Harry Potter. Rowling, of course, is the creator of the Harry Potter series - “one of the most successful writers the world has ever known,” crowed Neil Blair of the Christopher Little Literary Agency, which represents her. Warner Brothers, meanwhile, holds the license to the Harry Potter movies. And though Warner appears to be footing much of the bill, Rowling appears to be the party driving the litigation.

“I feel as though my name and my works have been hijacked, against my wishes, for the personal gain and profit of others and diverted from the charities I intended to benefit,” she said in a declaration to the court.

And what perfidious act of “hijacking” has RDR Books committed? It planned to publish a book by Steven Vander Ark, a former school librarian who for the past half-decade or so has maintained a fan site called the Harry Potter Lexicon. The Lexicon prints Harry Potter essays, finds Harry Potter mistakes, explains Harry Potter terminology, devises Harry Potter timelines, and does a thousand other things aimed at people who can’t get enough Harry Potter. In sum, it’s a Harry Potter encyclopedia for obsessive fans.

So long as the Lexicon was a Web site, Rowling looked kindly upon it; she once gave it an award and claimed to use it herself at times. But when Vander Ark tried to publish part of the Lexicon in book form - and (shudder!) to make a profit from his labors - Rowling put her foot down. She claims that she hopes to publish her own encyclopedia someday and donate the proceeds to charity; a competing book by Vander Ark would hurt the prospects for her own work.

But more than that, she is essentially claiming that the decision to publish, or to license, a Harry Potter encyclopedia is hers alone, since, after all, the characters in her books came out of her head. They are her intellectual property. And in her view, no one else can use them without her permission.

“There have been a huge number of companion books that have been published,” Blair said. “Ninety-nine percent have come to speak to us. In every case they have made changes to ensure compliance. They fall in line.” But in the case of the Lexicon, he said, “these guys refused to contact us.”

“They refused to answer any questions,” Blair said. “They refused to show us any details.”

They fall in line. There, in that one angry sentence, lies the reason that Falzone and his colleagues have agreed to help represent RDR Books. And in a nutshell, it’s why Lessig decided to start the Fair Use Project.

It’s a tad ironic that this dispute centers on a book, because ever since the recording industry began suing Napster, most of the big legal battles over copyright have centered on the Internet. The lawsuit Viacom filed against YouTube last year to prevent people from posting snippets of Viacom’s copyrighted television shows is the most obvious recent example.

But if you look a little further back, you’ll see that for a very long time now, copyright holders have made a series of concerted efforts to both extend copyright protection, and to make it an ever-more powerful instrument of control. More than a century ago, copyrights lasted for 14 years - and could be extended another 14 if the copyright holder petitioned for the extension. Today, corporate copyrights last for 95 years, while authors retain copyright for 70 years after their death. The most recent extension of copyright, passed by Congress in 1998, was driven in no small part by Disney’s desire to prevent Mickey Mouse and several of its other classic cartoon characters from falling into the public domain.

. . . .

At the same time, though, copyright holders have tried to impose rules on the rest of us - through threats and litigation - that were never intended to be part of copyright law. They sue to prevent rappers from taking samples of copyrighted songs to create their own music. Authors’ estates try to deprive scholars of their ability to reprint parts of books or articles because they disapprove of the scholar’s point of view. Lessig likes to cite a recent, absurd case where a mother put up on YouTube a video of her baby dancing to the Prince song “Let’s Go Crazy” - and Universal Music promptly sent her a cease-and-desist letter demanding that she remove the video because it violated the copyright.

There is no question that these efforts have had, as we like to say in the news business, a “chilling effect.” Roger Rapoport, who owns RDR Books, told me that ever since the case was filed, he has heard dozens of horror stories. “One university publisher told me they have given up literary criticism because of this problem,” he said.

. . . .

About a decade ago, though, Lessig decided to fight back. His core belief is that copyright protection, as he put to me, “was meant to foster creativity, not to stifle it” - yet that is how it is now being used. He fought the copyright extension of 1998 all the way to the Supreme Court. (He lost.) He founded a group called Creative Commons, which is, in a sense, an alternative form of copyright, allowing creators to grant far more rights to others than the traditional copyright system. And he founded the Fair Use Project to push back against, well, against copyright hogs like Rowling.

No one is saying that anyone can simply steal the work of others. But the law absolutely allows anyone to create something new based on someone else’s art. This is something the Internet has made dramatically easier - which is part of the reason why we’re all so much more aware of copyright than we used to be. But it has long been true for writers, film-makers and other artists. That’s what “fair use” means.

And that is what is being forgotten as copyright holders try to tighten their grip. Documentary film makers feel this particularly acutely, for instance. My friend Alex Gibney, who directed the recent film “Taxi To The Dark Side,” about torture, tried to get Fox to license him a short clip from the television series “24” to illustrate a point one of his talking heads was making about how the show portrays the use of torture at the CIA. Fox denied his request. Gibney, a fair use absolutist, used it anyway - but many filmmakers would have backed away.

Which is also why the Harry Potter Lexicon case is so important. For decades, fair use has been thought to extend to the publication of companion books that build on the work of someone else - so long as the new work adds something new and isn’t simply a rehash of the original. There are dozens of companion books to the Narnia chronicles, for instance, or the works of J.R.R. Tolkien.

. . . .

And, in a roundabout way, that gets us back what the Internet has wrought. For, as Lessig points out, “anybody who owns a $1,500 computer” can now create culture that is based on someone else’s creation. Indeed, we do all the time - on Facebook, on YouTube, everywhere on the Internet. If the creation of that content is deemed to be a violation of copyright, Lessig said, “then we have a whole generation of criminals” - which is terribly corrosive to the society. But if it is fair use, as it ought to be, then it becomes something quite healthy - new forms of free expression and creativity.

Link to the rest at The New York Times

From the U.S. Copyright Office:

More Information on Fair Use

Fair use is a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances. Section 107 of the Copyright Act provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research—as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use. Section 107 calls for consideration of the following four factors in evaluating a question of fair use:

- Purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes: Courts look at how the party claiming fair use is using the copyrighted work, and are more likely to find that nonprofit educational and noncommercial uses are fair. This does not mean, however, that all nonprofit education and noncommercial uses are fair and all commercial uses are not fair; instead, courts will balance the purpose and character of the use against the other factors below. Additionally, “transformative” uses are more likely to be considered fair. Transformative uses are those that add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work.

- Nature of the copyrighted work: This factor analyzes the degree to which the work that was used relates to copyright’s purpose of encouraging creative expression. Thus, using a more creative or imaginative work (such as a novel, movie, or song) is less likely to support a claim of a fair use than using a factual work (such as a technical article or news item). In addition, use of an unpublished work is less likely to be considered fair.

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole: Under this factor, courts look at both the quantity and quality of the copyrighted material that was used. If the use includes a large portion of the copyrighted work, fair use is less likely to be found; if the use employs only a small amount of copyrighted material, fair use is more likely. That said, some courts have found use of an entire work to be fair under certain circumstances. And in other contexts, using even a small amount of a copyrighted work was determined not to be fair because the selection was an important part—or the “heart”—of the work.

- Effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work: Here, courts review whether, and to what extent, the unlicensed use harms the existing or future market for the copyright owner’s original work. In assessing this factor, courts consider whether the use is hurting the current market for the original work (for example, by displacing sales of the original) and/or whether the use could cause substantial harm if it were to become widespread.

In addition to the above, other factors may also be considered by a court in weighing a fair use question, depending upon the factual circumstances. Courts evaluate fair use claims on a case-by-case basis, and the outcome of any given case depends on a fact-specific inquiry. This means that there is no formula to ensure that a predetermined percentage or amount of a work—or specific number of words, lines, pages, copies—may be used without permission.

Please note that the Copyright Office is unable to provide specific legal advice to individual members of the public about questions of fair use.

Link to the rest at U.S. Copyright Office

PG says that, while there are areas of legal clarity regarding what is and what is not fair use under US copyright law, the boundary between those two sets of rights includes some gray areas.

If you look at the Copyright Office explanation above, you’ll find a list of fundamental descriptions of fair use:

- Purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

- Nature of the copyrighted work

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

- Effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work

Concepts like purpose and character of the use, amount and substantiality of the portion used and effect of the use upon the potential market include a number of bright legal lines, but have also left quite a lot of gray areas that have been the subject of lots of litigation.

In the nature of litigation decisions, the more valuable the copyright, the more likely the owner of the copyright (or her attorneys) will be to carefully examine each instance where a work by another author seems similar in some ways to the original creation.

In addition to infringing the creator’s copyright, there is also an issue of trademark rights. As a general proposition, the title of a book is not protectable as a trademark. That said, “Harry Potter” is definitely a trademark and if you decide to publish a book titled, “Harry Potter and The Grinch,” you’re likely to hear from Ms. Rowling (or maybe Warner Brothers) and attorneys for Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P.

Here’s a link to the details about the U.S. trademark for The Grinch.

Pottermore heralds ‘exceptional’ year as profits soar by 150%

From The Bookseller:

Pottermore Publishing, the digital content company for J K Rowling’s Wizarding World, saw revenues rise by around a quarter to £40.4m while pretax profits rocketed 150% to £9.5m.

The company reported details of its financial results on 31st January covering the period for the 12 months to 31st March 2021. It has not yet made its accounts public at Companies House.

Revenues saw an uplift of 23% from £32.5m in 2020 to £40.4m while pretax profits soared from £3.8m to £9.5m.

The company said: “Pottermore Ltd had an exceptional year benefitting from a significantly increased appetite for digital reading during the pandemic, strong sales performance of the Harry Potter e-books and digital audiobooks and continued investment in franchise planning in partnership with Warner Bros.

“The Harry Potter At Home campaign, delivered by Wizarding World Digital LLC, further supported reading during the lockdown of 2020. This saw celebrities from the Wizarding World and beyond read from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Bloomsbury Children’s). The chapter reads were made available free of charge on www.wizardingworld.com. Pottermore Publishing also worked with partners such as Audible and Overdrive during this time to allow free access to the audio book and e-book of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in multiple languages.”

Link to the rest at The Bookseller

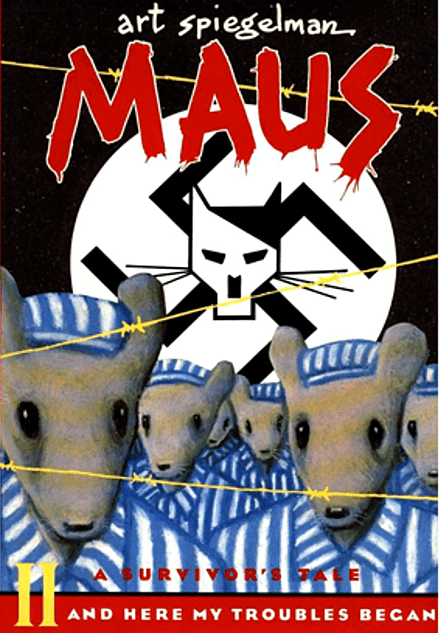

‘Maus’ Tops Amazon Bestseller List After Tennessee School Board Pulls Graphic Novel

From The Wall Street Journal:

“Maus,” a graphic novel about the Holocaust published decades ago, reached the top of Amazon.com Inc.’s bestsellers list after a Tennessee school board’s decision to remove the book spurred criticism nationwide.

“The Complete Maus,” which includes the first and second installments of Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel, sat at the top of Amazon’s bestseller list Monday morning. It later moved to the No. 2 spot. Separate copies of the installments, published in 1986 and 1991, respectively, were also among the top 10 bestselling books on the retail giant’s website.

Attention to the graphic novel was renewed this month when the McMinn County Board of Education in Athens, Tenn., voted unanimously to remove “Maus” from its eighth-grade curriculum. The 10-member board cited “vulgar” words that appeared in the book as well as subjects they deemed inappropriate for eighth-graders.

The school board’s Jan. 10 decision sparked widespread criticism. In an interview with CNBC last week, Mr. Spiegelman said he was baffled by the move, calling it “Orwellian.” A representative for Mr. Spiegelman said he wasn’t available for further comment Monday.

. . . .

In “Maus,” Mr. Spiegelman examines the horrors of the Holocaust and his parents’ journey of survival, depicting Nazis as cats and Jewish people as mice. The nearly 300-page graphic novel received a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992.

The McMinn County Board of Education said the graphic novel “was simply too adult-oriented” and cited the use of profanity, nudity, and depictions of violence and suicide. In a statement last week, the board said it doesn’t dispute the importance of teaching students about the Holocaust and said it asked administrators to find more age-appropriate texts to “accomplish the same educational goal.”

“The atrocities of the Holocaust were shameful beyond description, and we all have an obligation to ensure that younger generations learn from its horrors to ensure that such an event is never repeated,” the board said in a statement last week. “We simply do not believe that this work is an appropriate text for our students to study.”

Link to the rest at The Wall Street Journal (PG apologizes for the paywall, but hasn’t figured out a way around it.)

Students Called Radicals by Superintendent Fundraise for Freedom to Read

From Book Riot:

On January 25th, Granbury Independent School District in Texas pulled 100 books for review based on Matt Krause’s list of 850 books he wants banned from school libraries. Five books were pulled from shelves. Students spoke out at the board meeting,

On January 25th, Granbury Independent School District in Texas pulled 100 books for review based on Matt Krause’s list of 850 books he wants banned from school libraries. Five books were pulled from shelves. Students spoke out at the board meeting, saying,

We want to learn about things that may not be the prettiest or the most comfortable, but we as students are entitled to complete knowledge…

In response, superintendent of the district Jeremy Glenn said,

We want to learn about things that may not be the prettiest or the most comfortable, but we as students are entitled to complete knowledge…

In response, superintendent of the district Jeremy Glenn said,

Let’s not misrepresent things. We’re not taking Shakespeare, Hemingway off the shelves, and we’re not going and grabbing every socially, culturally, or religiously diverse book and pulling them. That’s absurd. And the people that are saying that are gaslighters, and it’s designed to incite division.

He went on to discuss “radicals” in school board meetings that he claims are sowing division in the community.

The students speaking out at the school board meeting decided to take these accusations and use them to raise money to fight censorship.

. . . .

They are selling a tee shirt with the text “radical gaslighter” on it, and all proceeds go to the Freedom to Read Foundation.

Link to the rest at Book Riot

PG notes that this particular censorship apparently originated with right-wing critics. In the US in recent years, censorship and book bans have primarily been from the Woke left.

The cover version is a misunderstood musical form

From The Economist:

Chan marshall (pictured), who goes by the stage name Cat Power, has been a fixture on the American indie-rock scene since the mid-1990s. She is a highly regarded artist, praised for her sombre, powerful songwriting and sound. Her 11th album, “Covers”, a set of versions of previously recorded songs, was released this month. It will be the third such LP she’s put out, following “The Covers Record” (2000) and “Jukebox” (2008); they make up more than a quarter of her total album releases.

It is noteworthy that Ms Marshall, or any musician, makes the distinction between “covers” and “original music” at all. For the first six decades of the recorded-music era, which began in earnest in the early 20th century, there was a clear division of labour: writers wrote and singers sang. Two industries—the recording one, and the songwriting one—grew up in parallel. In America, the writing arm was nicknamed Tin Pan Alley, and the business was concentrated on a single Manhattan street. Tin Pan Alley’s early fortune lay in sheet music, and a popular song could sell in the millions.

As recorded music took over, professional songwriters remained in demand. Even the rock’n’roll era merely shifted the action 20 blocks north, to the Brill Building. Competing versions of numbers jockeyed for position in the charts; the idea that a song could belong to a particular artist, other than in a strict licensing sense, had little traction. A “standard” was just that—a song so widely performed that only a very special reading could affix it to any one artist.

Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams were prominent singer-songwriters in the early-to-mid-20th century, but both were anomalies. Two acts were chiefly responsible for a major shift in the early 1960s: Bob Dylan and The Beatles. These performers created a wider perception that the writer and the artist not only could be, but should be, one and the same. Their youthful stardom, aided by a new mass media (and television in particular), popularised the idea of the musical auteur. By 1985 Mr Dylan was in a position to boast that: “Tin Pan Alley is gone. I put an end to it. People can record their own songs now.”

This was an oversimplification. Work by Mr Dylan and the Beatles was at the time covered widely, and lucratively—in Mr Dylan’s case, often before he had released a recorded version, making him a kind of one-man Tin Pan Alley in himself. In the 2010s he recorded three consecutive sets of pre-rock’n’roll American pop standards, a loving tribute to the very songs he once claimed to have made obsolete.

This in turn raises the question: what exactly constitutes an “original”? Does a musician “cover” a songwriter, or a recording? Ms Marshall’s album features a version of “These Days”, written by Jackson Browne, and first recorded by Nico in 1967. Mr Browne would not release a version until 1973, and his iteration bore a notable resemblance to a country-rock arrangement issued by Greg Allman earlier that year. Ms Marshall’s spare, folky take steers closest to the Nico version (on which Mr Browne played a distinctive guitar part), and includes a verse Nico performed but Mr Browne later omitted. So is she covering Nico, or Mr Browne? To whom does the song “belong”?

You might argue that if it belongs to anybody, a song belongs to whoever delivers it most memorably. Elvis Presley was above all an interpreter, and a superb one. “Hound Dog”, “Blue Suede Shoes”, “Suspicious Minds” and (until Pet Shop Boys audaciously reworked it) “Always On My Mind” have long been thought of as “Elvis songs”, yet all are cover versions. Nina Simone and Johnny Cash—no mean songwriter, either of them—likewise possessed a gift for claiming spiritual ownership of any song they covered.

An outstanding cover version can wrest a song from the grasp of even the biggest stars. So commanding is Sinéad O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares To U”, for example, that it relegates the song’s author, Prince, to a footnote. Even Mr Dylan is not impervious to this phenomenon; when touring for the first time since he recorded it, he played his song “All Along The Watchtower” not in the subdued folk-pop style of the original of 1967, but as a searing blast of rock plainly indebted to the authoritative version of 1968 by the Jimi Hendrix Experience (pictured above). In effect, he was covering a cover of his own song.

Link to the rest at The Economist

PG says copyright is a wondrous and multi-faceted bundle of rights.

The difference between

The difference between false memories and true ones is the same as for jewels: It is always the false ones that look the most real, the most brilliant.

Salvador Dali

Losing native languages is painful. But they can be recovered

From The Economist:

Memory is unfaithful. As William James, a pioneering psychologist of the 19th and early 20th centuries, observed: “There is no such thing as mental retention, the persistence of an idea from month to month or year to year in some mental pigeonhole from which it can be drawn when wanted. What persists is a tendency to connection.”

Julie Sedivy quotes James in a poignant context in her new book “Memory Speaks”. She was whisked from Czechoslovakia with her family at the age of two, settling eventually in Montreal. In her new home she became proficient in French and English, and later became a scholar in the psychology of language. But she nearly lost her first language, Czech, before returning to it in adulthood. Her book is at once an eloquent memoir, a wide-ranging commentary on cultural diversity and an expert distillation of the research on language learning, loss and recovery.

Her story is sadly typical. Youngsters use the child’s plastic brain to learn the language of an adoptive country with what often seems astonishing speed. Before long it seems to promise acceptance and opportunity, while their parents’ language becomes irrelevant or embarrassing, something used only by old people from a faraway place. The parents’ questions in their home language are answered impatiently in the new one, the children coming to regard their elders as out-of-touch simpletons who struggle to complete basic tasks.

For their part, meanwhile, the parents cannot lead the subtle, difficult conversations that guide their offspring as they grow. As the children’s heritage language atrophies, the two generations find it harder and harder to talk about anything at all.

Children often yearn desperately to fit in. Often this can mean not only learning the new language, but avoiding putting off potential friends with the old. Children, alas, can also be little bigots. At the age of five, researchers have found, they already express a preference for hypothetical playmates of the same race as them. They also prefer friends who speak only their language over those who speak a second one as well.

In theory, keeping a language robust once uprooted from its native environment is possible. But that requires the continuance of a rich and varied input throughout a child’s development—not just from parents, but through activities, experiences, books and media. These are often not available in countries of arrival. Parents are themselves pressed to speak in the new language to their children, despite evidence that their ungrammatical and halting efforts are not much help.

But a dimming language may not be as profoundly lost as speakers fear when, as adults, they visit elderly relatives or their home countries and can barely produce a sentence. Though the language may not be as retrievable as it once was, with time and exposure it can be relearned far faster than if starting from scratch.

Link to the rest at The Economist

Making Numbers Count

From The Wall Street Journal:

When Alfred Taubman was chief executive of the restaurant chain A&W, he came up with a clever way of challenging the competition: He offered a third-pound burger for the cost of a McDonald’s quarter-pounder. The result? More than half of A&W’s customers seethed, convinced that they were being asked to pay the same amount for what sounded to them like a smaller burger.