From The Economist:

Aaron was winding up a work call as his partner Jim waited at the dinner table. “I’ll just be a minute or two here,” Aaron whispered, cupping his phone. “No probs,” Jim whispered back.

Minutes passed and Aaron was still pacing around the apartment with the phone to his ear. Turning to Jim, he pointed to the phone with a roll of the eyes, mouthing the word “Sorry”. Jim waved away the apology with a good-natured shake of the head.

Five minutes later, Aaron was on the call, but seemed to have zoned Jim out. He spoke volubly, dusting his talk with the jargon of “leverage”, “buy-ins” and “scalability” that he knew Jim, a musician, hated with a passion. The carbonara Jim had made began to congeal.

Eventually, he turned around and was surprised to see Jim staring dejectedly into the middle distance. In an undertone, he told his colleague he had dinner waiting. Half an hour had passed.

Aaron hurried to the table, telling Jim a little too excitedly how delicious the pasta looked. “Help yourself,” Jim replied, a thunderous expression on his face.

“Oh God,” said Aaron, “You’re upset!”

“Yeah, funny that,” Jim replied, “Lost my appetite too.” He left the table.

Aaron shouted his apologies but all he heard was the slam of the door.

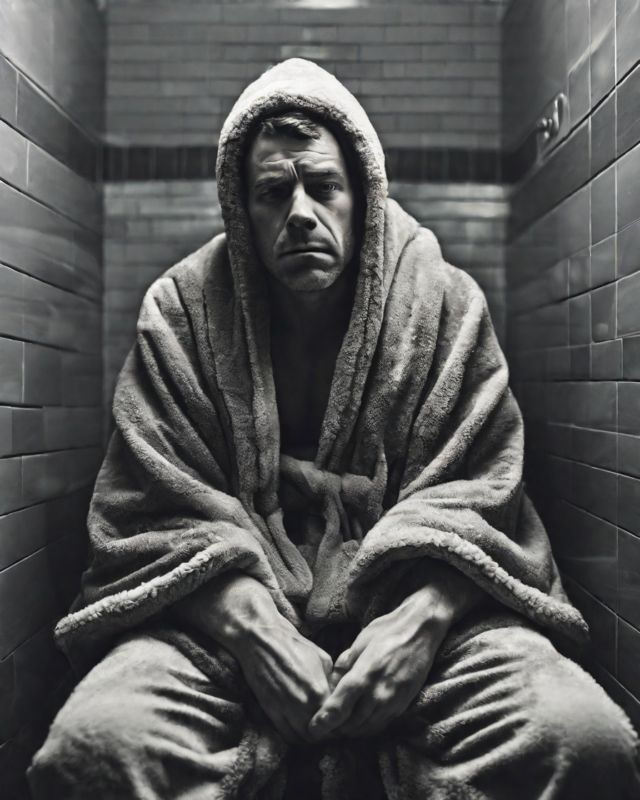

The following morning Aaron related the incident to me from the couch in my consulting room. It struck me as an object lesson in the arts of passive aggression, one of those behavioural tendencies which, like chronic overwork or narcissistic displays, has become a defining symptom of the modern world.

Passive aggression is the surreptitious, indirect and often insidious means by which we express antagonism or noncompliance while ensuring the plausible deniability of any such intentions

Passive aggression is the surreptitious, indirect and often insidious means by which we express antagonism or noncompliance while ensuring the plausible deniability of any such intentions. It can breed quickly: Aaron’s passive aggression provoked a peevish response from Jim. Though it may be practised at home, passive aggression flourishes in the workplace, where more direct expressions of frustration and resentment are considered unprofessional.

We can all think of examples: the resentful time-server who, when asked about an overdue report by his line manager, mumbles that “in the mass of your requests, it got forgotten” – not accidentally, the passive voice is usually passive aggression’s preferred verbal form. The colleague who is reliably generous with “compliments” such as “Your presentation was surprisingly good.” The boss who wonders at hometime whether his employee might want to stay a little late for the call with California.

In these instances, hostile or obstructive behaviour is at once performed and disavowed, so that the offender can assure you that he or she certainly didn’t intend whatever irritation you may now feel. It leaves you feeling, perhaps, that you’re the one with the problem. Strikingly, passive aggression is a strategy that can be adopted by both the boss class and its minions.

This strategy provides the perfect cover for myriad behaviours: procrastination or forgetfulness, often to knowingly destructive effect, accompanied by excuses that border on accusations (“I think I did tell you when you asked me that I’ve been very stressed lately”); antipathy that is skilfully projected onto its object by way of insincerity (“I’m sorry if you took exception to what I said”); as well as a constant yet barely perceptible attitude of resentment.

Such habits are exacerbated by the rise in remote working. Modes of communication like email and Slack easily amplify our suspicions of others’ secret hostility. Hastily written messages don’t lend themselves to nuances of inflection. What might sound playful or helpful when spoken in person may well read as sarcastic or resentful when read on a screen. No wonder, therefore, that passive aggression has thrived as we see less of our colleagues.

The unsurpassed model for passive aggression is the titular protagonist of Herman Melville’s celebrated story, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” (1853). Bartleby is the cadaverous, “pitiably respectable” young man who takes up a post as a copyist in a legal firm headed by the unnamed narrator, an attorney of sunny disposition.

After a brief stint of executing his copying tasks with exaggerated speed and efficiency, Bartleby abruptly responds to the attorney’s request to examine a paper with the now famous refrain, “I would prefer not to” – after which he downs tools entirely but refuses to leave the office, spending the nights there as well as days. Somehow, by obdurately retreating into silence and inactivity, Bartleby manages to dismantle the entire firm.

Bartleby’s riposte may be the most crystalline expression of passive aggression ever coined. He doesn’t outright refuse to examine the document. To a boss, refusal is unlikely ever to be welcome, but it’s at least intelligible, precisely because it signals an active stance.

We can all think of examples: the resentful time-server who, when asked about an overdue report by his line manager, mumbles that “in the mass of your requests, it got forgotten”

“I would prefer not to,” in contrast, is an absence of stance. It demands nothing, refuses nothing and so disables in advance any possible comeback. “You will not?” the narrator asks him in response, apparently seeking to coax from his employee an explicit expression of defiance that would justify sanction. “I would prefer not,” corrects Bartleby, as though clarifying for his employer that he is merely describing his inclination rather than making any statement of intent.

In its extreme non-commitment, Bartleby’s refrain throws some light on how more ordinary forms of passive aggression work, raising the conundrum of how we can possibly argue with or object to an attitude that refuses to reveal itself.

. . . .

I teach at a university and I remember a colleague in another institution telling me about a junior lecturer raising the issue of administrative workloads in one such meeting. The unnamed targets of her intervention were two or three professors especially adept at evading the large admin load with which all other colleagues were burdened. “I think it’s very important”, she said with a tight smile, “that admin is evenly distributed across the department so that we all have time to do our research.” (Note once again the preference for the passive voice.)

“Well,” responded one of the offending professors with a much broader smile, “I know I for one am very grateful to colleagues who make up for publishing less with more admin.” He said this knowing full well that junior colleagues were prevented from publishing more because of their bureaucratic burdens. The dishonest attack was presented as a warm expression of collegial gratitude – and the junior lecturer, in spite of her full awareness of what he was doing, was reduced to silence.

Passive aggression is one of those psychological terms, like “narcissistic”, “paranoid” and “bipolar”, whose casual popular use has gradually drained it of precision. Its deployment in modern psychiatry hasn’t tended to help matters.

The psychiatric history of the term is confused. Since 1952, when the first edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM), the bible of modern psychiatric practice, was published, the idea of passive aggression as a discrete personality disorder has oscillated in and out of favour.

What might sound playful or helpful when spoken in person, may well read as sarcastic or resentful when read on a screen. No wonder, therefore, that passive aggression has thrived as we see less of our colleagues

Christopher Lane, a historian of psychology, has shown that the authors of the first edition of the DSM lifted the criteria for the diagnosis of a passive-aggressive personality type from a 1945 report of Colonel William Menninger, an army psychiatrist, who lamented the proliferating avoidance of military duties by American soldiers employing “passive measures such as pouting, stubbornness, procrastination, inefficiency and passive obstructionism” in the face of “routine military stress”. Think of the hapless soldiers and pilots of Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22”, whose entirely rational aversion to dangerous military operations is taken as a symptom of mental illness.

Menninger’s list of traits was wrenched out of its context and pasted verbatim into the DSM’s diagnostic code, where it was quickly invoked in such wildly different contexts as marital therapy and adolescent delinquency. When behavioural traits are generalised, they cease to be seen as reactions to particular contexts – say, the fear of being killed on the battlefield – and instead are regarded, as Lane puts it, as “biological and neurological malfunctions”, the product of maladapted personalities.

The problem with pathologising human traits such as stubbornness, inefficiency and procrastination – to which were added, in the third edition of the DSM, dawdling and forgetfulness – is that they surely apply in some degree to all of us. (These traits, along with the entire diagnosis, were later removed.) But this insight is hard to hold onto when we’re so busy accusing others of mental disorders, a tendency which social media have exacerbated.

In a culture in which complex human traits become fodder for simplistic moral judgments, passive aggression is always going to be a problem of another, maladjusted individual. But perhaps it makes more sense to think of it as a dynamic within relationships, a current that passes between friends, colleagues, couples and families rather than a quality of particular personalities. One consequence of thinking about it this way is that we are made to recognise passive aggression is lurking in all of us.

Aaron and I had barely begun to reflect on what had happened the previous evening before he launched into an anxious flurry of self-justification.

“I mean, what does he want from me? He knows how important this deal is! Apparently I’m supposed to break off an important call because his tummy’s rumbling?!”

Aaron paused. His tone, tentative and defensive until now, suddenly became distinctly harsh: “Besides, he doesn’t complain about the money I bring in with a deal like this. We couldn’t afford the flat if we were both playing sax in tiny jazz venues!”

I remarked how resentful he sounded. Was that then what the incident was really about?

“Oh come on,” Aaron protested. “That’s not fair, that’s not what I meant! You sound like Jim now.” Aaron wasn’t entirely off the mark here. The art of psychotherapy involves confronting the patient with difficult truths. Though its conscious intent is to be empathetic and non-judgmental, the combination of deliberate pushback and measured tone can easily resemble passive aggression.

Aaron paused and continued. “Jim’s always saying I resent him because I earn so much more…”

“And?”

There was a pregnant pause before Aaron took an audibly sharp intake of breath. “Look,” he said, “when I think about it there was this, this fleeting moment last night. I really had intended to end that call in a couple of minutes, but I caught this sight of him of this…good little boy waiting patiently for Daddy and…I had this thought, I mean, I’m really not proud to say this, but it just came into my head, ‘Yeah, that’s right, you sit and twiddle your thumbs while I do the important stuff.’”

. . . .

“So you really were angry enough to want to remind him who’s in control,” I said.

By now he sounded upset. “I don’t know where it comes from in me…And now it occurs to me I was enjoying that power over him. Christ. That is so awful.”

Why was Aaron’s recognition of a seam of anger and resentment bubbling under the surface of his relationship so shameful? Aaron’s mother had more than once told him, with some satisfaction, of how she’d brought his toddler tantrums under control by leaving the room every time they started.

What happens to anger and aggression when they’re outlawed and denied any outlet for expression? Psychoanalysis understands aggression as a drive, an internal force that is constantly exerting pressure on our minds and bodies to discharge itself. According to a narrow definition, this might mean shouting or squaring off or even a physical blow. But it would be better to characterise aggression as any form of self-assertion, whether in word or deed. We cannot, for example, insist to a parent, teacher or boss on our right to speak without summoning up some aggressive energy.

The problem for Aaron was that he had long been phobic of explicit acts of aggression, whether in himself or anyone else. Direct confrontation with older siblings at home, or bullies at school, would make him stammer and shake helplessly.

But a fear of directly expressing oneself does not put the aggressive drive out of service. Psychoanalysis posits that a drive is quite different from a biological instinct. The latter is innately programmed and largely invariant. Predation in animals, for example, involves the stronger animal overpowering the weaker. If the lion doesn’t catch the antelope, it doesn’t then seek to persuade the antelope that its interests are best served by being torn apart and eaten.

The drive is altogether more wily and flexible. If it can’t find satisfaction through the direct route, it will find an indirect one through which it can assert itself while evading detection. Aaron couldn’t bring himself to tell Jim about his resentment; in fact, he was frightened of acknowledging it even to himself. But his mind devised a way of bypassing his conscious intent and giving expression to his anger towards Jim.

Aggression can disguise itself in many ways, but undoubtedly the most effective in societies governed by intricate behavioural codes is to appear as its opposite.

Aaron offered Jim not a single cross word or angry gesture. On the contrary, he apologised for keeping him waiting. The consistent defence of the passive aggressive person, frequently accompanied by wide eyes, open mouth and outstretched arms, palms up, seems apposite here: “What? I didn’t do anything!

As society has elevated the status of victims past and present, it is unsurprising that passive aggression has become one of the dominant social dynamics of our age

”The implication of this startled protestation of innocence is that if I wasn’t doing anything, I can’t possibly be accused of hostility. This apparently logical defence highlights the oxymoronic nature of the term passive aggression. A defence like this relies on a binary understanding: one is either mild or furious, friendly or hostile – or passive or aggressive. It assumes that “doing” happens only actively, forgetting the powerful consequences, so vividly manifested by Bartleby, of doing nothing. This is where the concept of the drive proves so useful, for it accounts for how we act in ways that we’re not fully aware of, if at all.

Lest we imagine passive aggression as something done by a calculating perpetrator to an innocent victim, it is worth looking at Jim’s role in the incident. At no point during Aaron’s epic call did Jim remind him of his presence or tell him that if he didn’t get off the phone he’d start dinner without him. Passive aggression is almost always a language unconsciously shared between unspoken adversaries. Instead of having stand-up rows which each sought to win, Aaron and Jim seemed to fight for the status of more worthy and ill-treated victim, the winner being whoever extracted more guilt from the other. As society has elevated the status of victims past and present, it is unsurprising that passive aggression has become one of the dominant social dynamics of our age.

From Thomas Hobbes onwards, a number of modern thinkers have seen the restraint of aggression as the basis of a functioning society. In “Civilisation and Its Discontents”, Sigmund Freud characterised passive aggression as part of the irresolvable tragedy of the human condition – the voracious will of the individual and the conformist demands of society are ultimately irreconcilable. On the eve of the second world war and just a few years after “Civilisation and Its Discontents” was published, the German sociologist Norbert Elias documented in “The Civilising Process” (1939) how the spread of manners across Europe over many centuries went hand in hand with the establishment of the modern state, suppressing the excesses of violence and sexual flagrancy in society.

Not all thinkers welcomed the repression of violence. Friedrich Nietzsche, who published “On the Genealogy of Morality” in 1887, just as Freud was conducting his first forays into psychotherapy, regarded morality as the ultimate form of passive aggression – a ruse employed by the weak, resentful masses to restrain the will of their stronger, creative superiors.

But the question we might ask of all these thinkers is why they think we’re instinctively inclined to be aggressive. The psychoanalytic answer is that there is nothing we fear more than feeling helpless – and this fear stalks us far more often than we might think. Aggression is a salve against feelings of helplessness, a way of assuring ourselves we are masters, rather than hapless victims, of the world around us. Aaron was phobic about direct confrontation because of a deep-rooted, unconscious conviction that it would lead to his rejection. Even the professor’s self-satisfied barb against his junior colleagues was provoked by the fear that his position in the hierarchy was under threat.

The great advantage of passive aggression is not only that it allows us simultaneously to exercise and to deny our aggression but that it weaponises our vulnerability. Instead of exposing our feelings of insecurity, passivity becomes a sneaky way of asserting ourselves. Perhaps we should call it aggressive passivity instead.

If we think of passive aggression less as a pathology in others and more as a common expression of fear of dependency, latent in us as well as family and colleagues, we might respond to it more humanely.

Can any of us claim never to have disguised a criticism as a compliment or “forgotten” to fulfil a request from someone we were secretly angry with? We do this not because we are power-crazed and manipulative, but because we retain a childlike fear of our own aggression and the terrible consequences it might entail for us.

Link to the rest at The Economist